Photos : © La Salle de bains

Photos : © La Salle de bains

The Nose

Du 30 janvier au 27 mars 2010From 30 January to 27 March 2010

Pour son exposition personnelle à la Salle de Bains, Mick Peter nous livre sa propre version de la nouvelle de Nicolas Gogol intitulée Le Nez (1835-36). À l’instar de l’adaptation que le compositeur de musique Dimitri Chostakovitch réalise dans les années 1930 pour un opéra, la présente interprétation relève de la fascination pour l’absurdité et l’humour cinglant du texte original.

Le Nez témoigne de la réalité grotesque de la ville de Saint-Pétersbourg, capitale érigée dans la plus grande incohérence et régie par la stupidité de son régime bureaucratique. Elle sert de cadre où s’agite une humanité au destin blafard. Parmi ce fourmillement, Gogol nous conte les aventures de Kovaliov, un agent de l’administration russe, assesseur de collège, dont le nez a subitement pris la fuite. Par le truchement des pérégrinations du nez devenu conseiller d’état et suivant la recherche de ce fugitif organe par son propriétaire, Gogol dresse un portrait satirique de Saint-Pétersbourg. Cette ville nouvelle, artificielle et trompeuse proclamée "fenêtre sur l’Europe" par l’Empereur Pierre Le Grand, n’est qu’un mythe ou une image.

L’existence de plusieurs fins pour cette nouvelle est une des caractéristiques de l’œuvre qui a retenu toute l’attention de Mick Peter. Gogol conclut tantôt sur le pourquoi d’une telle fiction ou sur la vraisemblance même de l’histoire. Cependant, l’errance du nez demeure peu explicable et finalement sans importance. De ces effets de distanciation et de cette conception de la fiction comme pure construction, Mick Peter tire de nouvelles formes habitées par l’amusement même que suscite la narration.

Reprendre Le Nez de Gogol, dont il n’existe pas vraiment de version définitive, semble donc en soi tout à fait grotesque. Si tant est que cette entreprise, basée sur une narration délirante, puisse procéder d’une quelconque idée directive, la version de Mick Peter résulte d’une réaction en chaîne ou d’un effet de répétition. Il s’est en effet inspiré de l’opéra de Chostakovitch qui est donc une reprise du Nez de Gogol, Mick Peter emboîte ainsi le pas et explique que « l’adaptation se superpose à l’adaptation ». Les répétitions, variations et réinterprétations sont des processus de création et de production qui nourrissent autant l’histoire de l’art, de la littérature, du cinéma que celle de la musique pop. Remake ou cover du Nez de Chostakovitch, l’exposition de Mick Peter puise librement dans la mise en scène, en image et en musique du compositeur russe.

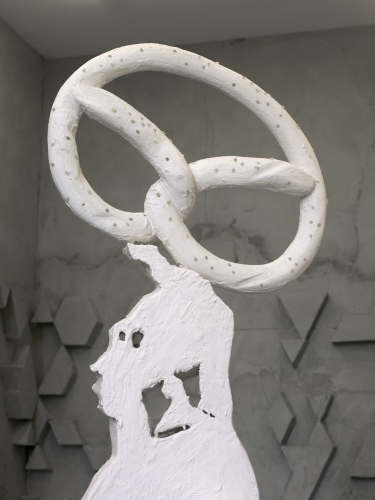

Les murs de l’espace d’exposition sont habillés de bas-reliefs qui pourraient servir de décors de théâtre ou encore d’un projet pour une sculpture publique. L’artiste joue avec les divisions possibles de l’espace architectural et des interfaces entre les murs et le sol. Les imposantes proportions, la couleur gris-ciment et l’aspect brut des surfaces illustrent l’urbanisme hostile de Saint- Pétersbourg telle l’atmosphère froide et embrumée de la nouvelle de Gogol. Toujours sous l’emblème de l’opéra de Chostakovitch, l’exposition s’avère tour à tour hostile et enthousiaste aux élans créatifs de toute sculpture narrative. Des silhouettes humaines (ce qui est rare dans l’œuvre de Peter) se détachent d’un mur en partie recouvert d’une trame aux volumes géométriques vaguement psychédéliques. Un personnage-objet coiffé d’une bretzel se dresse tel un totem ou une sculpture clanique. Des cubes de polystyrènes paraissent durs comme de la pierre, mais ils semblent sur le point de s’effondrer et sont pour le moins menacés par les lames d’un grand rasoir de barbier.

Comme souvent dans l’univers de Mick Peter, les sculptures prennent ici la forme de créatures hybrides ou d’objets étrangement anthropomorphiques qui refusent la représentation figurative du corps et par ce biais toute expression de synthèse. Cette esthétique fragmentaire aux accents carnavalesques et folkloriques se superpose à la grille de la ville impersonnelle, que Gogol lui-même exécrait et opposait à la richesse culturelle de son paradis ethnique natal.

Les improbables juxtapositions de sculptures soulignent ici l’attrait de Mick Peter pour l’esthétique du décalage. L’œuvre de Gogol porte les germes de la modernité et préfigure d’une certaine façon l’esthétique surréaliste. L’opéra de Chostakovitch permet l’accomplissement de ce processus créatif construit sur de libres associations d’idées et sur une mise en scène proche de l’écriture automatique. De cette version livrée par Chostakovitch, Mick Peter n’emprunte pas seulement le côté formel explosif lié à la dramaturgie. Il explore le potentiel du montage musical de Chostakovitch, dont l’immense succès résulte en grande partie du mélange de compositions atonales, de chansons populaires et de musiques folkloriques. Pas de musique, ni de mouvement réel dans l’exposition de Mick Peter, mais de la matière habilement sculptée qui transpose cet assemblage des registres culturels dans le champ de la sculpture. L’effet produit est celui d’un bruit sourd ou d’un arrêt sur image juste avant le chaos. Les sculptures sont ainsi érigées telles des masses silencieuses et statiques, mais de façon éphémère, seulement le temps d’un spectacle.

Le Nez témoigne de la réalité grotesque de la ville de Saint-Pétersbourg, capitale érigée dans la plus grande incohérence et régie par la stupidité de son régime bureaucratique. Elle sert de cadre où s’agite une humanité au destin blafard. Parmi ce fourmillement, Gogol nous conte les aventures de Kovaliov, un agent de l’administration russe, assesseur de collège, dont le nez a subitement pris la fuite. Par le truchement des pérégrinations du nez devenu conseiller d’état et suivant la recherche de ce fugitif organe par son propriétaire, Gogol dresse un portrait satirique de Saint-Pétersbourg. Cette ville nouvelle, artificielle et trompeuse proclamée "fenêtre sur l’Europe" par l’Empereur Pierre Le Grand, n’est qu’un mythe ou une image.

L’existence de plusieurs fins pour cette nouvelle est une des caractéristiques de l’œuvre qui a retenu toute l’attention de Mick Peter. Gogol conclut tantôt sur le pourquoi d’une telle fiction ou sur la vraisemblance même de l’histoire. Cependant, l’errance du nez demeure peu explicable et finalement sans importance. De ces effets de distanciation et de cette conception de la fiction comme pure construction, Mick Peter tire de nouvelles formes habitées par l’amusement même que suscite la narration.

Reprendre Le Nez de Gogol, dont il n’existe pas vraiment de version définitive, semble donc en soi tout à fait grotesque. Si tant est que cette entreprise, basée sur une narration délirante, puisse procéder d’une quelconque idée directive, la version de Mick Peter résulte d’une réaction en chaîne ou d’un effet de répétition. Il s’est en effet inspiré de l’opéra de Chostakovitch qui est donc une reprise du Nez de Gogol, Mick Peter emboîte ainsi le pas et explique que « l’adaptation se superpose à l’adaptation ». Les répétitions, variations et réinterprétations sont des processus de création et de production qui nourrissent autant l’histoire de l’art, de la littérature, du cinéma que celle de la musique pop. Remake ou cover du Nez de Chostakovitch, l’exposition de Mick Peter puise librement dans la mise en scène, en image et en musique du compositeur russe.

Les murs de l’espace d’exposition sont habillés de bas-reliefs qui pourraient servir de décors de théâtre ou encore d’un projet pour une sculpture publique. L’artiste joue avec les divisions possibles de l’espace architectural et des interfaces entre les murs et le sol. Les imposantes proportions, la couleur gris-ciment et l’aspect brut des surfaces illustrent l’urbanisme hostile de Saint- Pétersbourg telle l’atmosphère froide et embrumée de la nouvelle de Gogol. Toujours sous l’emblème de l’opéra de Chostakovitch, l’exposition s’avère tour à tour hostile et enthousiaste aux élans créatifs de toute sculpture narrative. Des silhouettes humaines (ce qui est rare dans l’œuvre de Peter) se détachent d’un mur en partie recouvert d’une trame aux volumes géométriques vaguement psychédéliques. Un personnage-objet coiffé d’une bretzel se dresse tel un totem ou une sculpture clanique. Des cubes de polystyrènes paraissent durs comme de la pierre, mais ils semblent sur le point de s’effondrer et sont pour le moins menacés par les lames d’un grand rasoir de barbier.

Comme souvent dans l’univers de Mick Peter, les sculptures prennent ici la forme de créatures hybrides ou d’objets étrangement anthropomorphiques qui refusent la représentation figurative du corps et par ce biais toute expression de synthèse. Cette esthétique fragmentaire aux accents carnavalesques et folkloriques se superpose à la grille de la ville impersonnelle, que Gogol lui-même exécrait et opposait à la richesse culturelle de son paradis ethnique natal.

Les improbables juxtapositions de sculptures soulignent ici l’attrait de Mick Peter pour l’esthétique du décalage. L’œuvre de Gogol porte les germes de la modernité et préfigure d’une certaine façon l’esthétique surréaliste. L’opéra de Chostakovitch permet l’accomplissement de ce processus créatif construit sur de libres associations d’idées et sur une mise en scène proche de l’écriture automatique. De cette version livrée par Chostakovitch, Mick Peter n’emprunte pas seulement le côté formel explosif lié à la dramaturgie. Il explore le potentiel du montage musical de Chostakovitch, dont l’immense succès résulte en grande partie du mélange de compositions atonales, de chansons populaires et de musiques folkloriques. Pas de musique, ni de mouvement réel dans l’exposition de Mick Peter, mais de la matière habilement sculptée qui transpose cet assemblage des registres culturels dans le champ de la sculpture. L’effet produit est celui d’un bruit sourd ou d’un arrêt sur image juste avant le chaos. Les sculptures sont ainsi érigées telles des masses silencieuses et statiques, mais de façon éphémère, seulement le temps d’un spectacle.

For his solo show at la Salle de Bains, Mick Peter is offering us his own version of Nikolay Gogol’s story titled The Nose (1835-36). Like the musical adaptation made by the composer Dimitry Shostakovich in the 1930s for an opera, this interpretation stems from a fascination with the absurdity of the original text, and its scathing wit.

The Nose describes the grotesque reality of St. Petersburg, a capital city that was built with no eye whatsoever on coherence, and governed by the stupidity of its bureaucratic regime. It acts as a setting within which a human population tosses and turns at the mercy of a wan fate. Amidst all this bustle, Gogol tells us about the adventures of Kovaliov, an employee in the Russian administration — a college assessor who has suddenly been abandoned by his nose. By way of the roamings of this nose, now turned into a state councillor, and by following its owner’s quest for the runaway organ, Gogol paints a satirical portrait of St. Petersburg. This new, artificial and deceitful city, proclaimed to be a “window on Europe” by the emperor Peter the Great, is nothing more than a myth, and an image.

The fact that this story has several endings is one of the work’s features to have caught Mick Peter’s full attention. At times Gogol ends with the whys and wherefores of such a fiction, at others on the very probability of the tale. But the nose’s wanderings remain more or less inexplicable and, in the end of the day, of little significance. From these alienating effects of detachment and this conception of fiction as a pure construct, Mick Peter derives new forms, exercised by the actual amusement caused by the narrative.

So this re-use of Gogol’s The Nose, which does not really exist in any definitive version, thus seems, per se, altogether grotesque. If it is a fact that this undertaking, based on a frenzied narrative, can issue from some sort of guiding idea, Mick Peter’s version is the result of a chain reaction and an effect of repetition. He has actually drawn inspiration from Shostakovich’s opera, which is thus a remake of Gogol’s The Nose, following close on the composer’s heels: “adaptation overlaid on adaptation.” The repetitions, variations and re-interpretations are creative and productive processes which fuel the history of art, literature and film as much as they do the history of pop music. And as a remake of and cover for Shostakovich’s !e Nose, Mick Peter’s exhibition draws freely from the Russian composer’s stage direction, in terms of imagery and music alike.

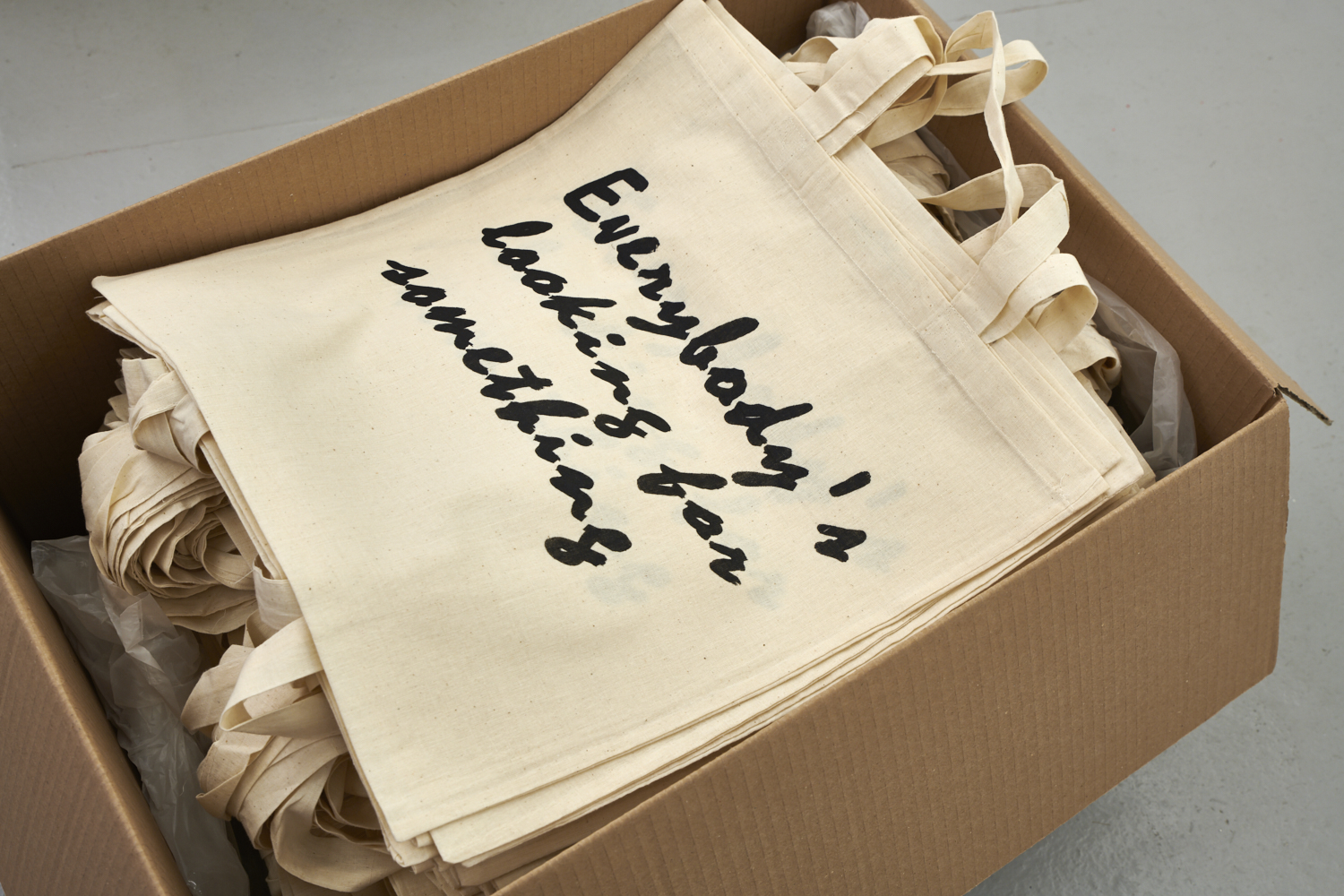

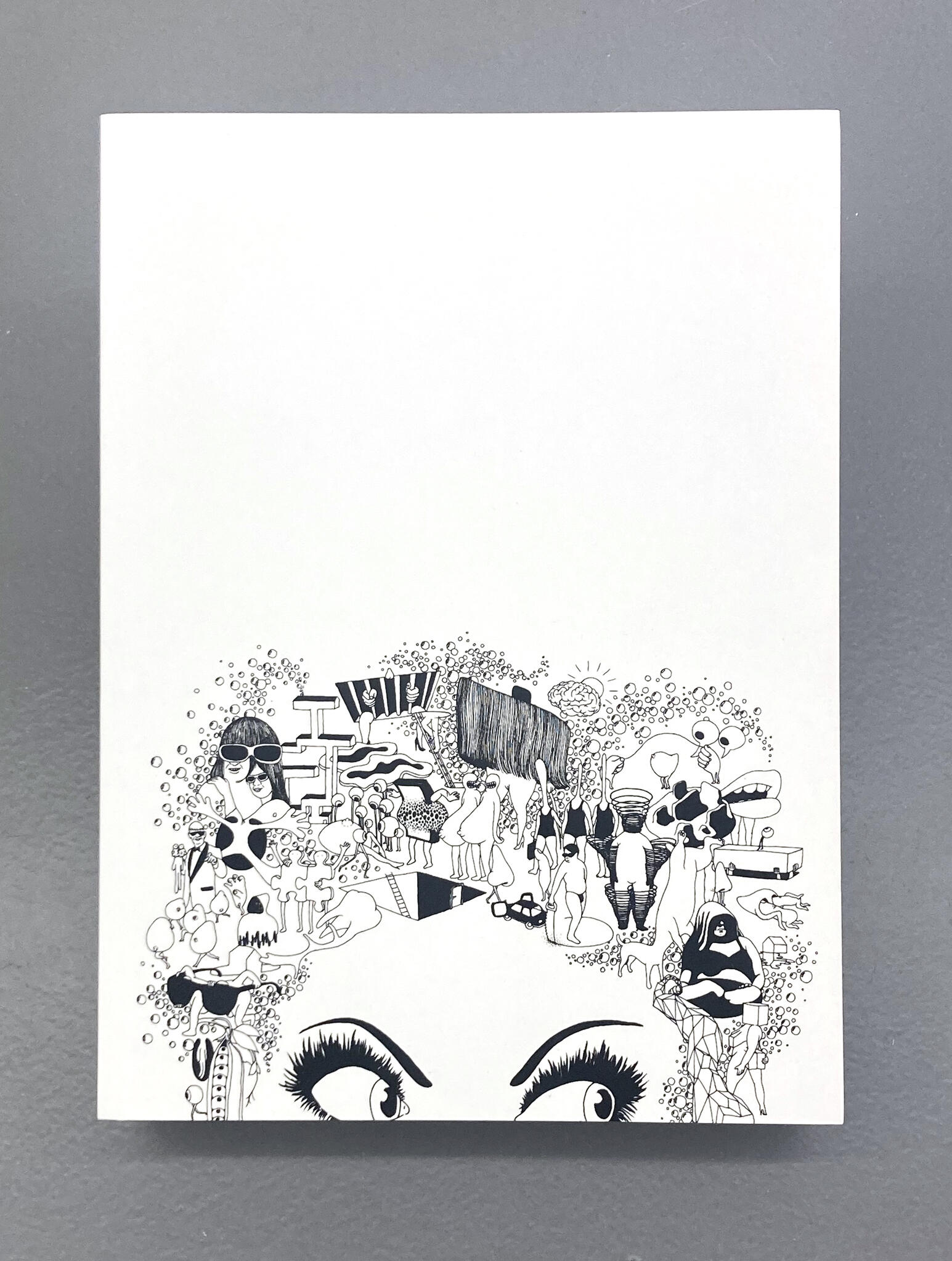

The walls of the exhibition venue are clad in bas-reliefs which might act as stage sets or alternatively as a public sculpture project. The artist juggles with the possible divisions of the architectural space and the interfaces between walls and floor. The impressive proportions, the cement-grey colour, and the rough look of the surfaces all illustrate the hostile urbanism of St. Petersburg, like the cold and misty atmosphere of Gogol’s story. Still under the aegis of Shostakovich’s opera, the exhibition is turn by turn hostile to and enthusiastic about the creative surges of any narrative sculpture. Human silhouettes (a rarity in Peter’s oeuvre) stand out from one wall. A figure-cum-object with a pretzel on its head rises up like a totem or clan sculpture. An assemblage of file boxes and office dossiers forms a column devoid of any architectonic function. Polystyrene cubes appear as hard as stone, but they seem on the point of collapsing and are, to say the least, threatened by the blades of a large barber’s razor.

As is often the case in Mick Peter’s world, the sculptures here take on the form of hybrid creatures and oddly anthropomorphic objects which reject any figurative representation of the body and, thereby, any synthetic expression. This fragmentary aesthetic with its carnival-like and folkloric emphases is overlaid on the grid of the impersonal city, which Gogol himself abhorred and contrasted with the cultural wealth of the ethnic paradise where he was born

The unlikely juxtapositions of sculptures here underscore Mick Peter’s attraction to the aesthetics of discrepancy and differentness. Gogol’s work contains the seeds of modernity and, in a way, foreshadows Surrealist aesthetics. Shostakovich’s opera permits the culmination of this creative process built on free associations of ideas and a presentation akin to automatic writing. From the version proposed by Shostakovich, Mick Peter borrows not only the formal, explosive aspect linked to dramaturgy; he also explores the potential for musical montage shown by Shostakovich, the huge success of which is largely the result of the mixture of atonal compositions, popular songs, and folkloric music. There is neither music nor real movement in Mick Peter’s exhibition, but rather cleverly sculpted matter which transposes this assemblage of cultural styles into the sculptural arena. The effect produced is one of a dull noise and a freeze frame just before chaos. The sculptures are thus erected like silent, static masses, but in an ephemeral way, for no longer than the duration of a spectacle.

The Nose describes the grotesque reality of St. Petersburg, a capital city that was built with no eye whatsoever on coherence, and governed by the stupidity of its bureaucratic regime. It acts as a setting within which a human population tosses and turns at the mercy of a wan fate. Amidst all this bustle, Gogol tells us about the adventures of Kovaliov, an employee in the Russian administration — a college assessor who has suddenly been abandoned by his nose. By way of the roamings of this nose, now turned into a state councillor, and by following its owner’s quest for the runaway organ, Gogol paints a satirical portrait of St. Petersburg. This new, artificial and deceitful city, proclaimed to be a “window on Europe” by the emperor Peter the Great, is nothing more than a myth, and an image.

The fact that this story has several endings is one of the work’s features to have caught Mick Peter’s full attention. At times Gogol ends with the whys and wherefores of such a fiction, at others on the very probability of the tale. But the nose’s wanderings remain more or less inexplicable and, in the end of the day, of little significance. From these alienating effects of detachment and this conception of fiction as a pure construct, Mick Peter derives new forms, exercised by the actual amusement caused by the narrative.

So this re-use of Gogol’s The Nose, which does not really exist in any definitive version, thus seems, per se, altogether grotesque. If it is a fact that this undertaking, based on a frenzied narrative, can issue from some sort of guiding idea, Mick Peter’s version is the result of a chain reaction and an effect of repetition. He has actually drawn inspiration from Shostakovich’s opera, which is thus a remake of Gogol’s The Nose, following close on the composer’s heels: “adaptation overlaid on adaptation.” The repetitions, variations and re-interpretations are creative and productive processes which fuel the history of art, literature and film as much as they do the history of pop music. And as a remake of and cover for Shostakovich’s !e Nose, Mick Peter’s exhibition draws freely from the Russian composer’s stage direction, in terms of imagery and music alike.

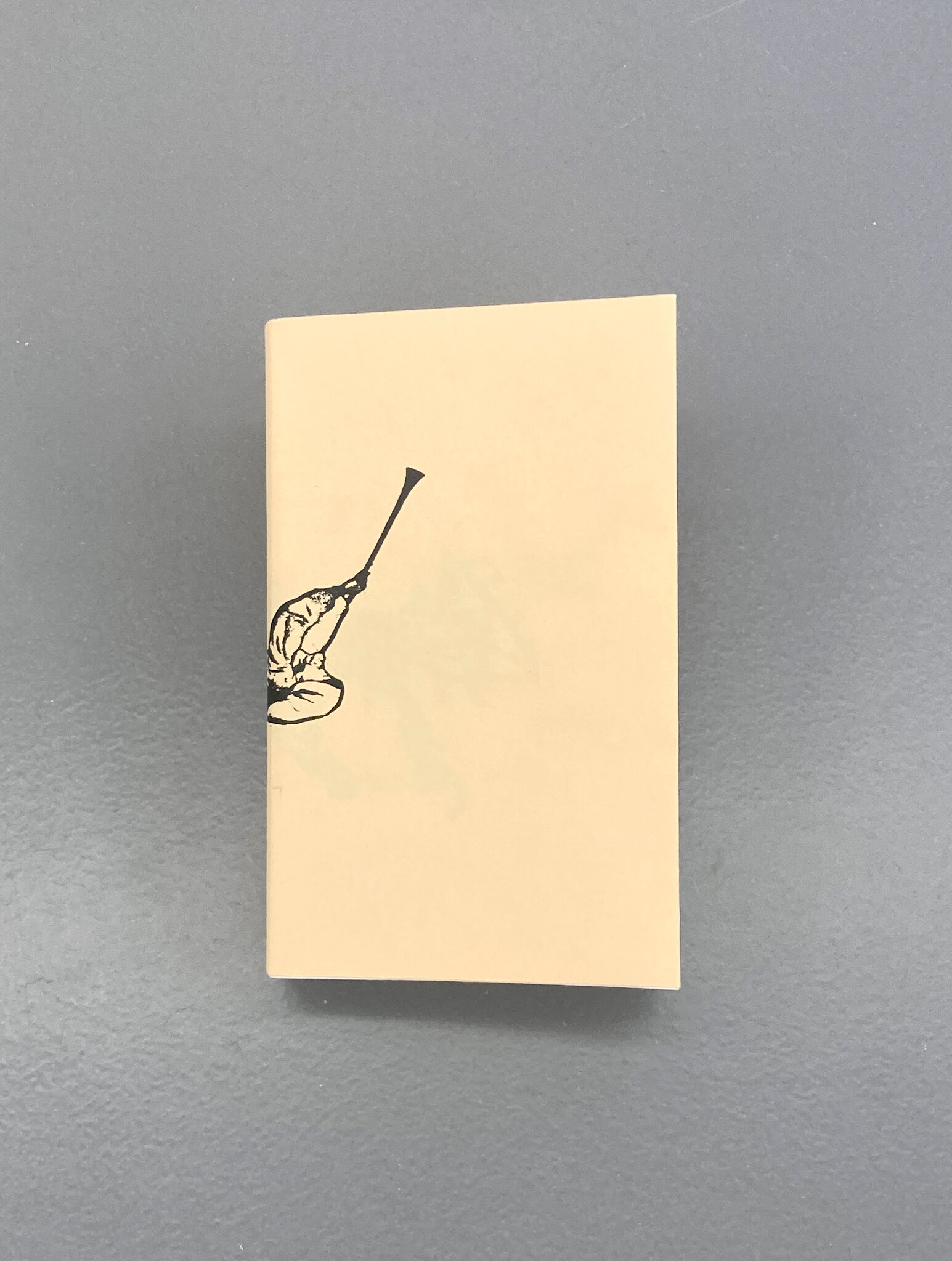

The walls of the exhibition venue are clad in bas-reliefs which might act as stage sets or alternatively as a public sculpture project. The artist juggles with the possible divisions of the architectural space and the interfaces between walls and floor. The impressive proportions, the cement-grey colour, and the rough look of the surfaces all illustrate the hostile urbanism of St. Petersburg, like the cold and misty atmosphere of Gogol’s story. Still under the aegis of Shostakovich’s opera, the exhibition is turn by turn hostile to and enthusiastic about the creative surges of any narrative sculpture. Human silhouettes (a rarity in Peter’s oeuvre) stand out from one wall. A figure-cum-object with a pretzel on its head rises up like a totem or clan sculpture. An assemblage of file boxes and office dossiers forms a column devoid of any architectonic function. Polystyrene cubes appear as hard as stone, but they seem on the point of collapsing and are, to say the least, threatened by the blades of a large barber’s razor.

As is often the case in Mick Peter’s world, the sculptures here take on the form of hybrid creatures and oddly anthropomorphic objects which reject any figurative representation of the body and, thereby, any synthetic expression. This fragmentary aesthetic with its carnival-like and folkloric emphases is overlaid on the grid of the impersonal city, which Gogol himself abhorred and contrasted with the cultural wealth of the ethnic paradise where he was born

The unlikely juxtapositions of sculptures here underscore Mick Peter’s attraction to the aesthetics of discrepancy and differentness. Gogol’s work contains the seeds of modernity and, in a way, foreshadows Surrealist aesthetics. Shostakovich’s opera permits the culmination of this creative process built on free associations of ideas and a presentation akin to automatic writing. From the version proposed by Shostakovich, Mick Peter borrows not only the formal, explosive aspect linked to dramaturgy; he also explores the potential for musical montage shown by Shostakovich, the huge success of which is largely the result of the mixture of atonal compositions, popular songs, and folkloric music. There is neither music nor real movement in Mick Peter’s exhibition, but rather cleverly sculpted matter which transposes this assemblage of cultural styles into the sculptural arena. The effect produced is one of a dull noise and a freeze frame just before chaos. The sculptures are thus erected like silent, static masses, but in an ephemeral way, for no longer than the duration of a spectacle.

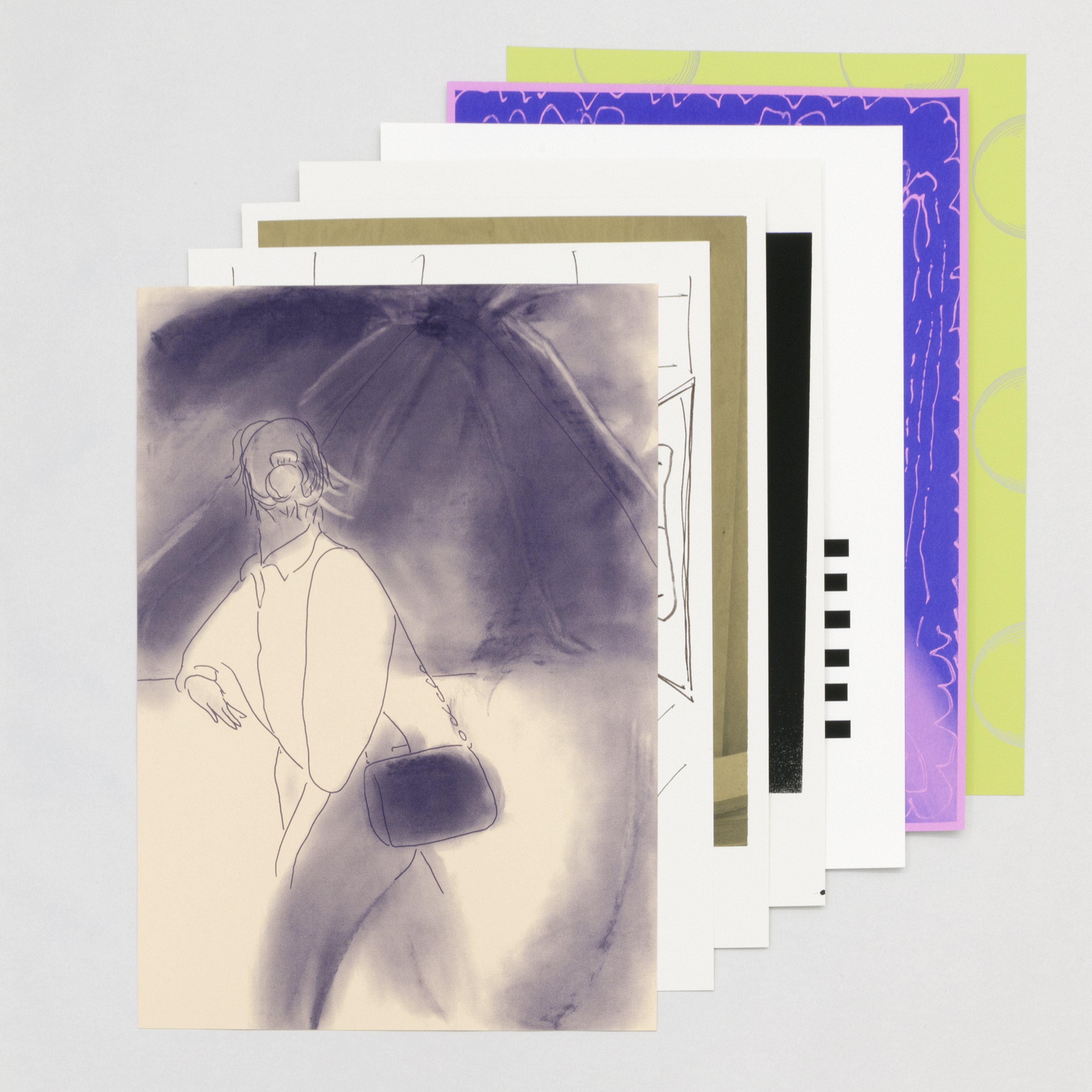

The Nose, 2010

carton d'invitation

Mick Peter, né en 1974 (Allemagne).

Vit et travaille à Glasgow.

Représenté par Crèvecœur.

Vit et travaille à Glasgow.

Représenté par Crèvecœur.

Mick Peter, né en 1974 (Allemagne).

Vit et travaille à Glasgow.

Représenté par Crèvecœur.

Vit et travaille à Glasgow.

Représenté par Crèvecœur.

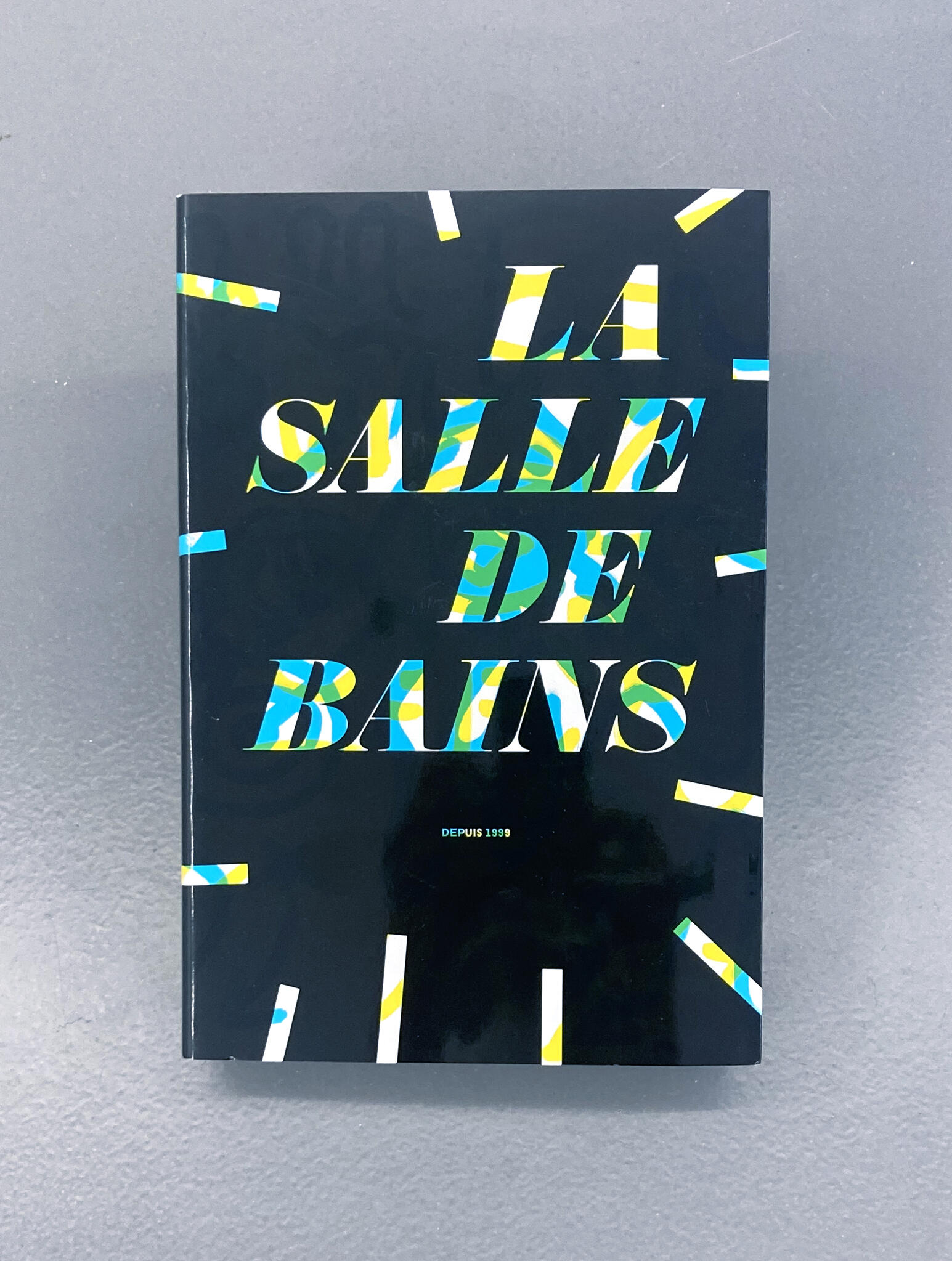

La Salle de bains reçoit le soutien du Ministère de la Culture DRAC Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes,

de la Région Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes et de la Ville de Lyon.

de la Région Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes et de la Ville de Lyon.