photos : Jesús Alberto Benítez

photos : Jesús Alberto Benítez

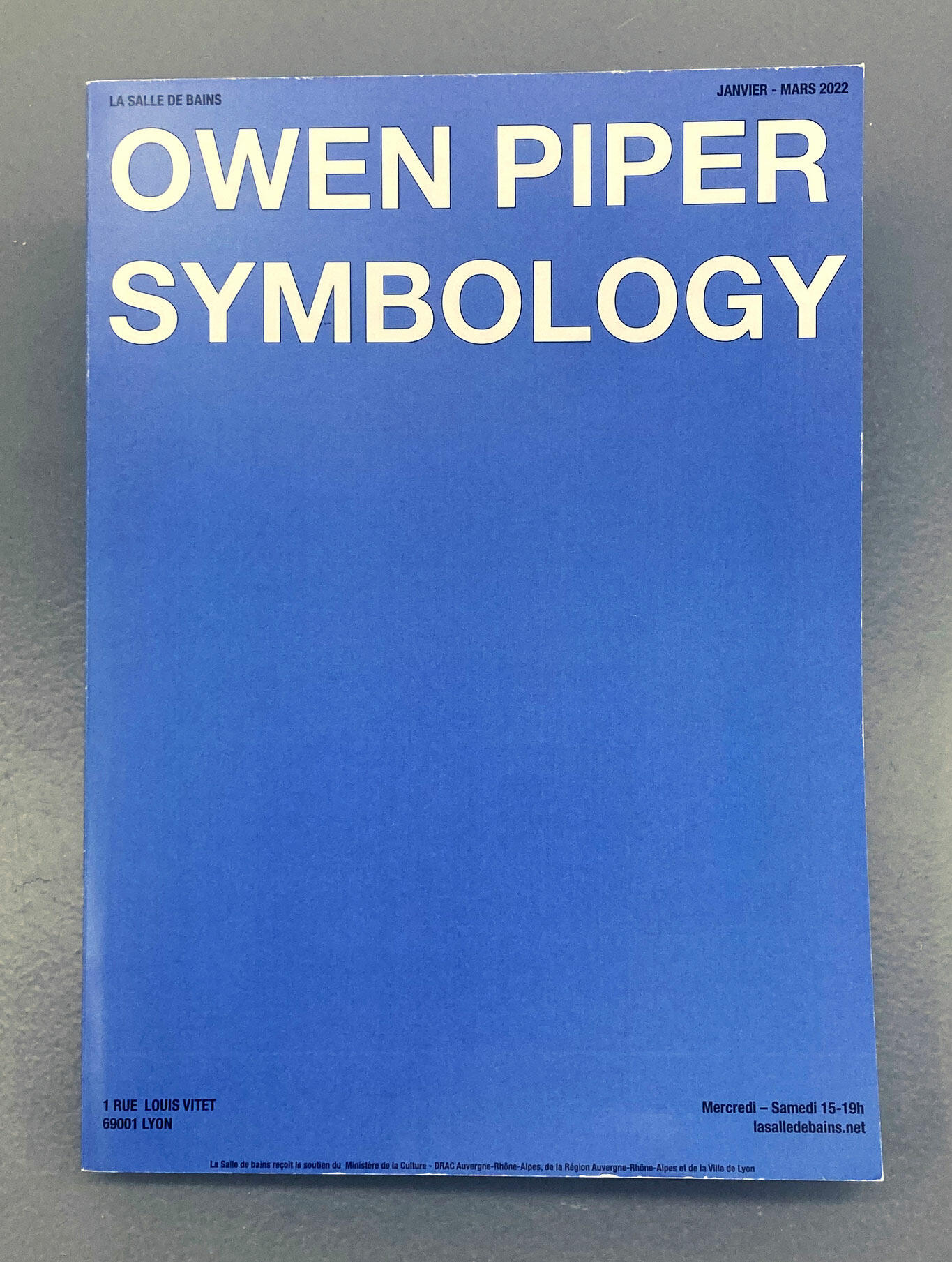

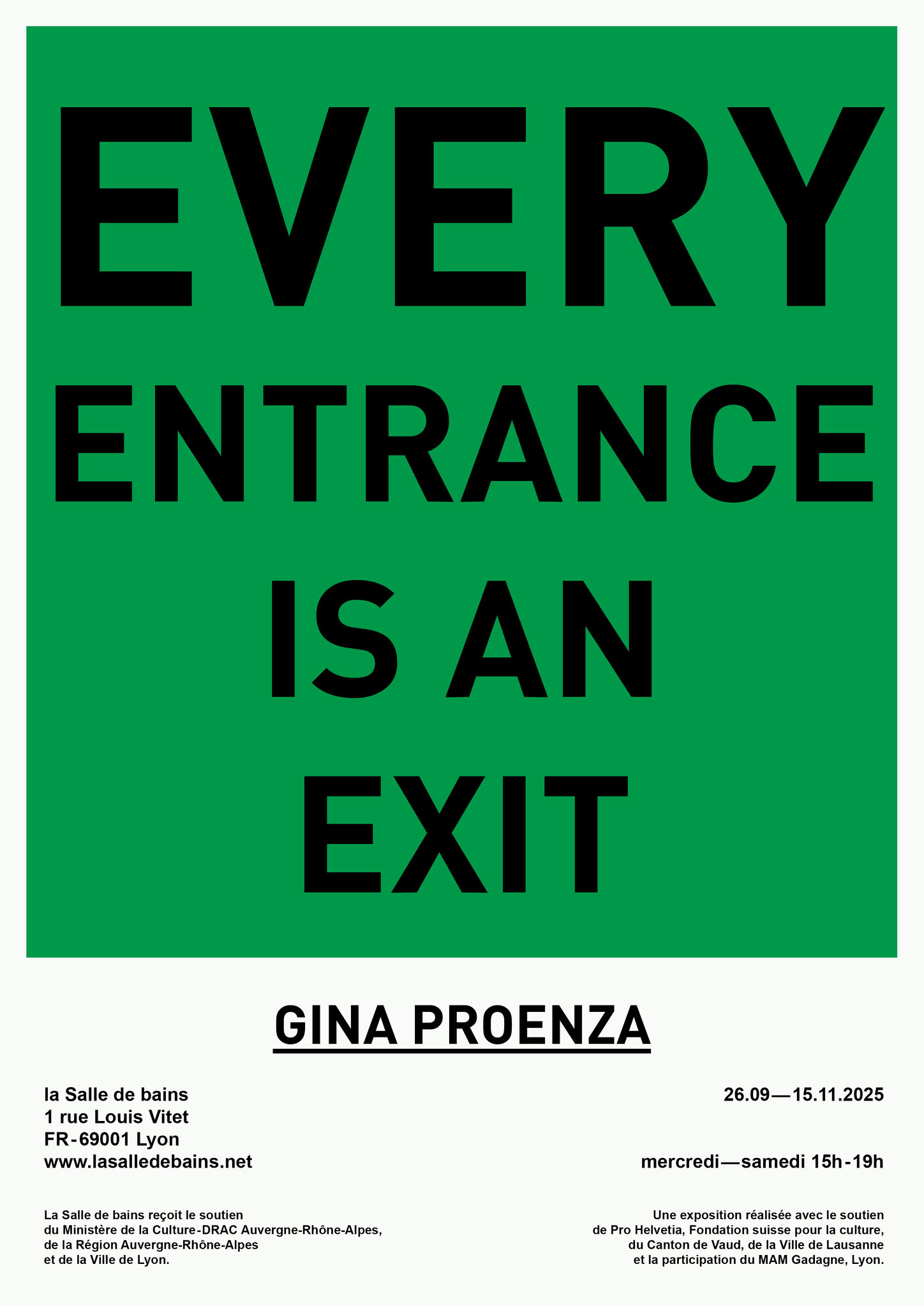

EVERY ENTRANCE IS AN EXIT – Salle 3

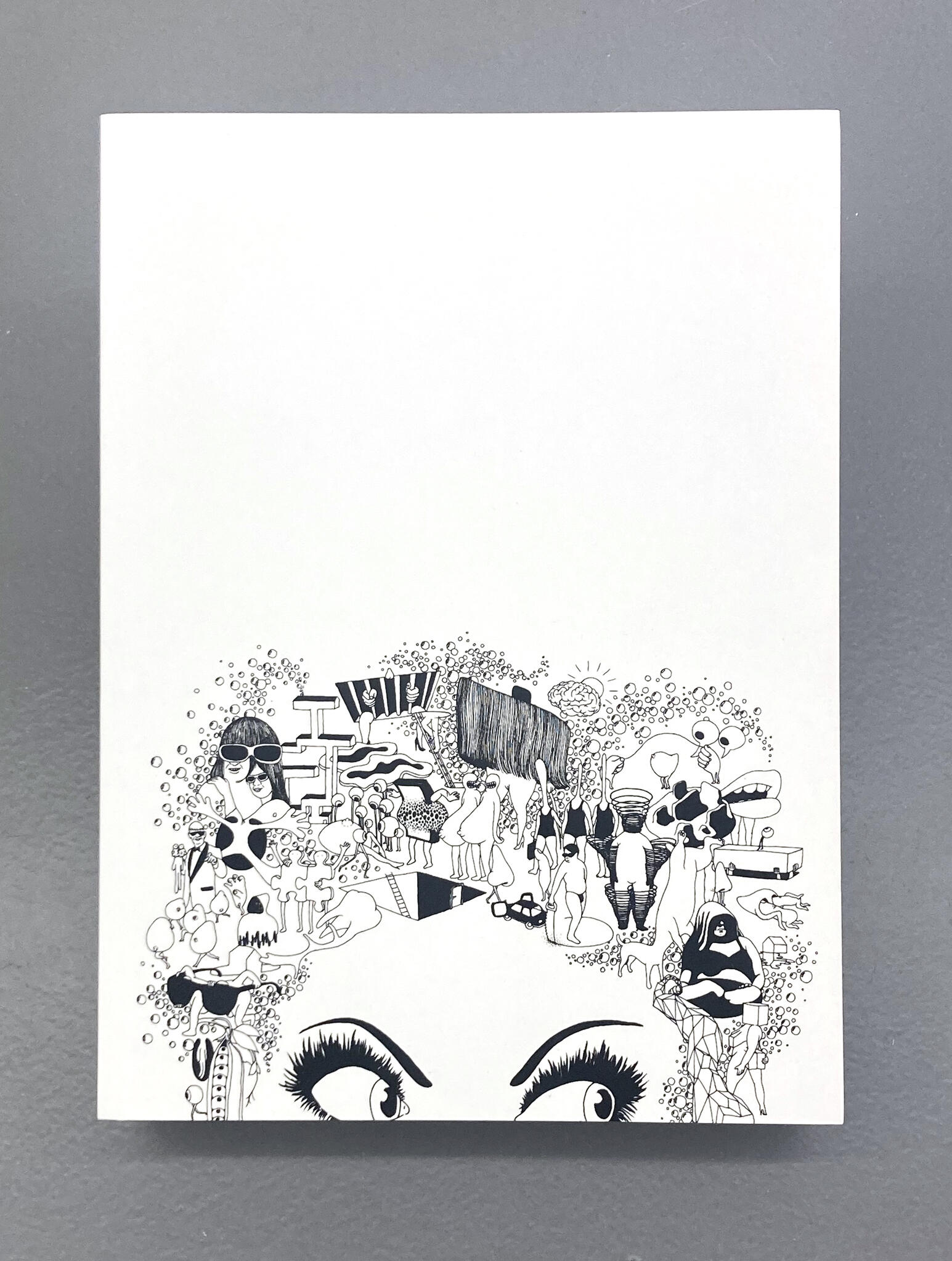

Gina Proenza déplace les mots dans les phrases ou retire des lettres dans les mots. Les jeux de translations qu’elle opère sur le langage pourraient aussi qualifier sa manière de faire de la sculpture, laissant advenir les images et les idées inattendues lorsque les choses ne sont plus à leur place.

L’accent autoritaire du titre de son exposition à la Salle de bains, une formule qu’on a cru lire sur un poste frontière, à l’entrée d’une boîte de nuit ou d’un musée – quand la sortie est définitive – est une reprise en miroir du titre d’un essai d’Anne Carson (1). Le texte parle d’un seuil, celui que l’autrice franchit la nuit, dans son sommeil, quand s’absenter du monde revient à entrer dans la dimension du rêve et se livrer à ses lois : l’énigme, l’étrange, où tout ce qui était familier devient inquiétant. À la Salle de bains, on pourra se demander de quel côté du seuil situer cette scène bureaucratique couleur menthe qui réunit des marionnettes de loups.

Au théâtre, les entrées et les sorties des comédien·nes sur scène ont un effet déterminant sur la compréhension de l’intrigue et des relations entre les personnages – qu’ils soient amis ou ennemis. Gina Proenza s’intéresse également à ce qui demeure de la présence des êtres et des choses en leur absence. C’est ainsi qu’après avoir visité la cité des gones, elle s’est demandée quelles seraient les conséquences sur les histoires qu’on raconte dans les théâtres de marionnettes si l’un des protagonistes en prenait congé.

Le loup est un personnage secondaire dans le théâtre de Guignol où il apparaît rarement sans le petit chaperon rouge et finit souvent par se faire corriger à coup de tavelle(2). Les contes moraux, en revanche, en ont fait une figure centrale, personnification du danger et de la perfidie dont la mise en garde a fini par éclipser les autres enjeux de pouvoirs et les rivalités au sein de la société humaine. Dans une relecture féministe, l'ethnologue Yvonne Verdier soulève que les versions écrites omettent certains épisodes de la tradition orale. Ainsi du repas anthropophage du petit chaperon rouge : le loup n’ayant mangé que la moitié de la grand-mère pour faire avaler des morceaux choisis (sang et tétons) à l’adolescente destinée à remplacer les femmes ménopausées dans la hiérarchie familiale (3).

Dans le monde réel, le retour des loups en zone pâturée a pris une dimension politique dès lors que l’impossible cohabitation entre le prédateur et les élevages a cherché à se résoudre dans la législation. Son déclassement d’espèce “strictement protégée” à “protégée” a été voté par la commission européenne en 2024 sous l’influence des partis conservateurs et peut-être, selon certains commentateurs, les états d’âme d’Ursula Von der Leyen dont la ponette préférée a été dévorée par un loup. Le gouvernement Français, quant à lui, vient d’annoncer qu’il autoriserait les tirs sur les exploitations agricoles moyennant une simple déclaration. Pour les groupes de défense de la faune sauvage, cela signifie que la chasse aux loups est ouverte.

La situation du loup n’est pas sans rappeler les procès faits aux animaux dans l’Europe médiévale, histoires auxquelles s’est intéressée Gina Proenza pour ce qu’elles disent encore aujourd’hui de la tentation de désigner un bouc émissaire quand se pose un problème de subsistance. La simplification du débat autour du loup – opposant ceux qui veulent sa survie à ceux qui veulent le tuer – ranime des réflexes archaïques, des peurs et des haines collectives, d’autant plus quand l’animal est, par nature, invasif (4).

C’est pourquoi le fauve connaît un grand succès littéraire au rayon philosophie, où la prise des armes contre l’ancêtre de son meilleur ami offre, il faut l’admettre, une terrible parabole. Selon certain·es penseur·euses, les loups ne sont pas revenus pour manger notre pitance mais pour nous mettre face à un problème métaphysique : celui de devoir renoncer à notre suprématie dans le règne animal en vue de notre propre survie. Il révèle l’urgence de nouveaux récits qui divergent de l’histoire écrite par les dominants décrivant le progrès de l’humanité dans la domestication et l’accumulation des richesses (5).

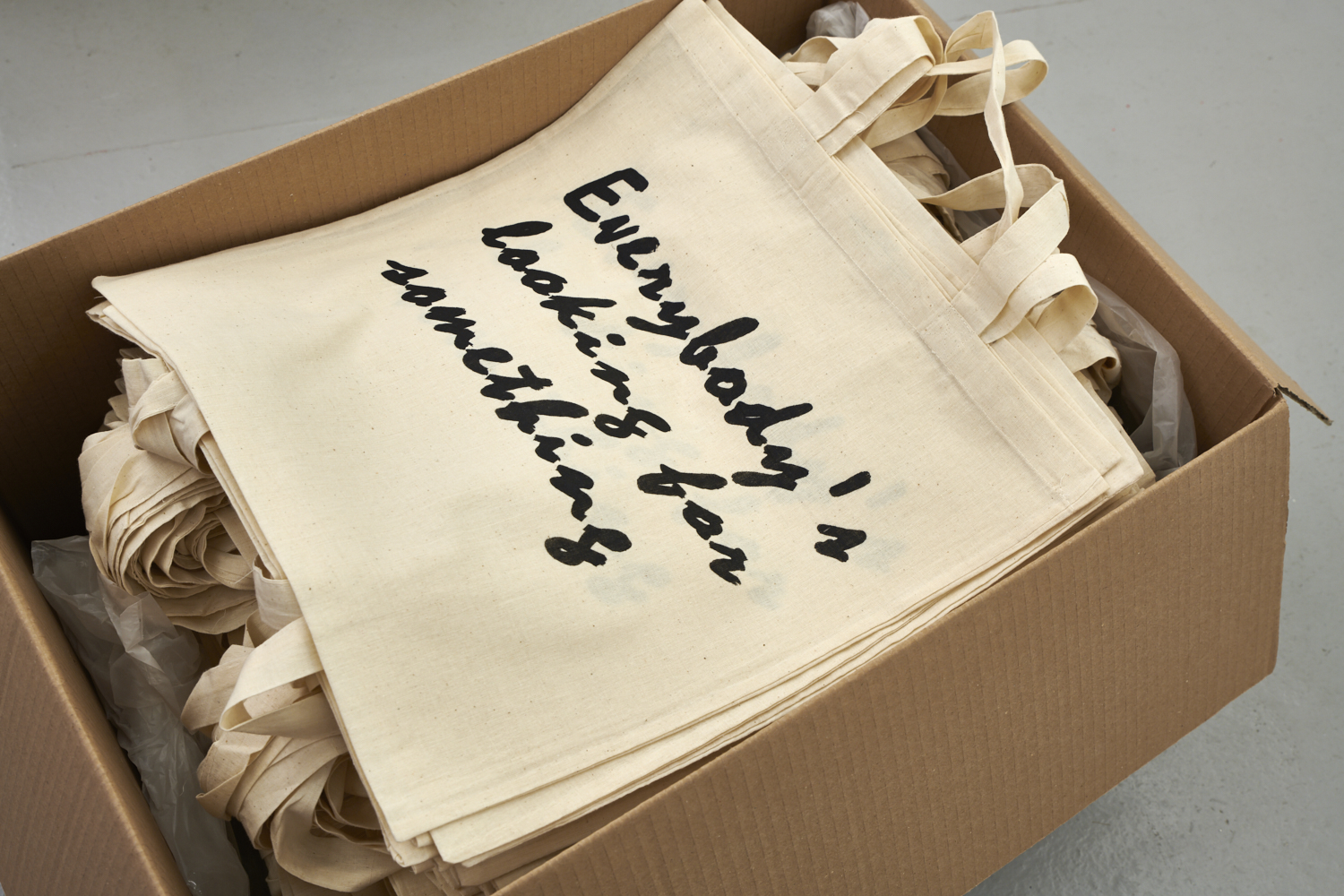

C’est dans cette urgence que s’immisce irrépressiblement des narrations au sein d’un geste relevant de la tradition de l’art conceptuel, à savoir délocaliser un ensemble d’objets dans l’espace d’exposition. Et c’est souvent par le truchement d’histoires mineures que Gina Proenza engage une critique de ses héritages artistiques occidentaux. Alors, que pourraient bien nous raconter ces marionnettes qui semblent prendre leur destin en main tandis qu’elles ne sont plus agies par des mains humaines ? Dans ce moment critique, le théâtre de Guignol – qui, avant de divertir les enfants, exposait les inégalités sociales et faisait des laissés pour compte les héros de l’histoire – pourrait-il nous être d’un quelconque secours?

Gina Proenza likes to shift words around in sentences or strategically remove certain letters from words. This play of transpositions in language could also characterize her way of working with sculpture, allowing unexpected images and ideas to pop up when things are no longer in their usual place.

The authoritarian note sounding in the title of her show at La Salle de bains, a statement you might read over a border post or at the entrance to a nightclub or museum – when the exit is final and there’s no going back – flips around two words in the title Anne Carson gave to one of her essays.1 Carson’s text speaks about a threshold, the one the author crosses at night in her sleep, when to be absent from the world amounts to entering the dimension of dreams and surrendering to the laws of the enigmatic, the odd, where everything that was familiar becomes disturbing. At La Salle de bains, visitors may indeed wonder on which side of the threshold exactly the bureaucratic mint-colored setting that features wolf hand puppets falls.

In theater the entrances and exits of the players on stage have a decisive effect on our understanding the plot and the connections between the characters, be they friends or enemies. The artist is also interested in what remains of the presence of beings and things in their absence. So she wondered, after visiting Lyon, the Cité des gones,2 about what the consequences would be for the stories told in puppet theaters if one of the protagonists were to decide to decamp.

The wolf is a secondary character in Lyon’s “Guignol” puppet theater, where he rarely appears without Little Red Riding Hood and often ends up being “corrected” (vigorously!) with a tavelle.3 Moral tales, on the other hand, have made him a central figure, the personification of danger and treachery whose warning has come to eclipse other questions of power and rivalries in human society. In a feminist rereading, the ethnologist Yvonne Verdier points out that the written versions omit certain episodes that exist in the oral tradition, Little Red Riding Hood’s cannibalistic meal, for example. In that iteration, the wolf devours only half of the grandmother and feeds select parts (blood and breasts) to the adolescent girl, who will eventually replace the menopausal women in the family hierarchy.4

In the real world the return of wolves to grazing lands assumed a political dimension when legislators sought to resolve the impossible coexistence of predator and livestock by passing laws. Downgrading the species from “strictly protected” to “protected” was voted on and passed by the European Commission in 2024 under the influence of conservative parties and perhaps, according to some observers, the President of the Commission, Ursula Von der Leyen, whose favorite pony had ended up as one wolf’s tartar buffet. The French government has just announced that it would authorize shooting the species on working farms, a simple declaration by the shooter being the only requirement. For wildlife advocacy groups, this is tantamount to open season on wolves.

The wolf’s situation recalls the actual legal trials of animals carried out in medieval Europe, stories that drew the artist’s attention because of what they tell us even today about the temptation to designate a scape goat when there arises a problem of subsistence, something threatening or undermining the resources needed for survival. The simplification, even dumbing down, of the debate over wolves – setting against each other those who want wolves to survive and those who want to kill them – revives archaic reflexes and collective fears and hatreds, especially when the animal is invasive by nature.5

This is the reason why wolves have enjoyed such literary success in philosophy, where taking up arms against a very close relative of man’s best friend provides, it must be said, a frightening parable. According to some thinkers, wolves haven’t come back to eat our meager lunch but to confront us with a metaphysical problem, whether we should or can give up our supremacy in the animal kingdom for the sake of our own survival. They reveal the urgency of new narratives that move away from history written by the top dogs describing humanity’s progress in taming nature and accumulating wealth.6

It is this urgency that narratives irrepressibly intrude on, within a gesture that partakes of the tradition of conceptual art, for instance by relocating a group of objects to the exhibition venue. And it’s often through minor stories that the artist critiques the legacies of Western art she has inherited. These puppets seem to be taking their fate into their own hands even while they are no longer brought to life by human ones. So what might they be telling us? At this critical juncture, could puppet theater, which had been in the business of exposing social inequalities and making the marginalized the heroes of history, before turning to entertain kids, be of any help?

(1) Every Exit is an Entrance (a praize of sleep) est publié dans le recueil Decreation en 2005.

(2) Instrument du métier à tisser qui sert de bâton à Guignol.

(3) Yvonne Verdier, Le petit chaperon rouge dans la tradition orale, Allia, 2014.

(4) Voir Ghassan Hage, Le loup et le musulman, l’islamophobie et le désastre écologique, 2021.

(5) Voir, entre autres, Donna Haraway, Manifeste des espèces compagnes, 2010.(1) “Every Exit Is an Entrance (A Praise of Sleep)” was published in Anne Carson’s collection Decreation in 2005.

(2) In the epithet Cité des gones, the noun gones is a term in the local dialect for “lads, kids, guys” generalized to any native of Lyon. For English readers, it’s also a happy coincidence, an echo for the ear and eye of the past participle “gone,” picking up the theme of disappearance (and reappearance elsewhere) that is present in the show.

(3) The tavelle is a wooden reel or bar in a loom from the days of silk weaving, a very important industry in Lyon. Guignol, the iconic hero of the tradition of puppet theater in France, in fact represented the worker in the silk industry. He wields a tavelle as a stick to bludgeon other characters who deserve the beating.

(4) Yvonne Verdier, Le petit chaperon rouge dans la tradition orale, Allia, 2014.

(5) See Ghassan Hage, Le loup et le musulman, l’islamophobie et le désastre écologique, 2021.

(6) See, for example, Donna Haraway, Manifeste des espèces compagnes, 2010.

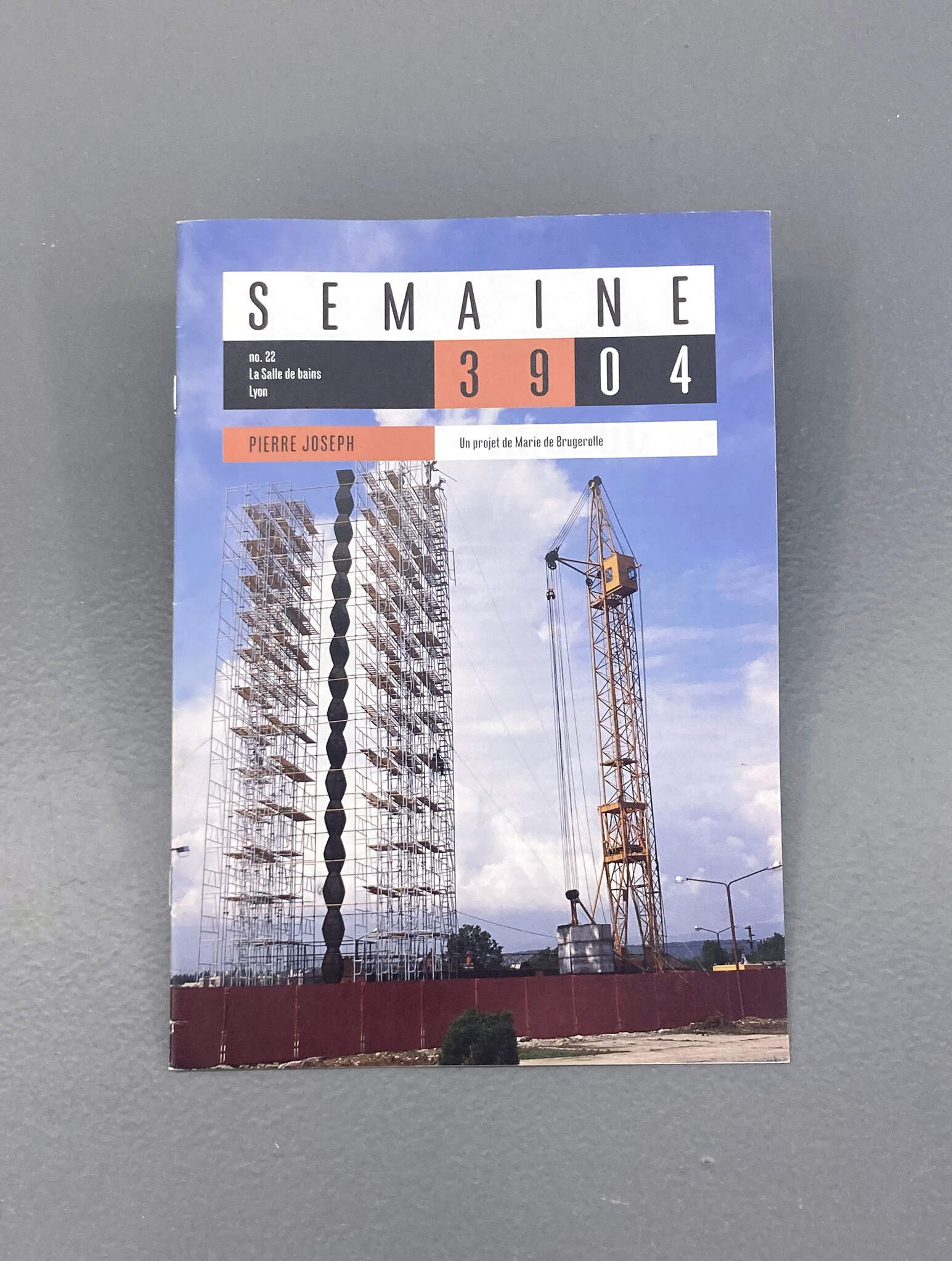

Liste des œuvres :

List of works :

marionnettes de loups empruntées, bois, peinture, photographies

Gina Proenza, Revolt, 2025

enseigne lumineuse

Gina Proenza, Jetlag, 2025

vidéo, 24:00:00

borrowed glove puppets, wood, paint, photographs

Gina Proenza, Revolt, 2025

neon sign

Gina Proenza, Jetlag, 2025

vidéo, 24:00:00

Gina Proenza, (*1994, Bogotá, Colombia), lives and works in Lausanne. She studied visual arts at ECAL and dramaturgy at the University of Lausanne and La Manufacture. She has held several solo exhibitions at the Musée Cantonal d'Art in Lausanne, the Musée des Beaux-Arts in La Chaux-de-Fonds, the KunstHalle Sankt-Gallen, the Centre d'Art Neuchâtel, and the Centre Culturel Suisse in Paris. In parallel with her artistic practice, she is involved in the emerging art scenes in the region, both as co-programmer of the Forde art space in Geneva (2020-2023) and co-founder of the artist-run space Pazioli artist-run space (Renens, 2015-2017) and, in 2025, co-programmer of Tunnel Tunnel in Lausanne. She teaches sculpture and runs the Écritures workshop at ECAL with Federico Nicolao.

L'exposition de Gina Proenza reçoit le soutien de Pro Helvetia, fondation suisse pour la culture, du Canton de Vaud et de la Ville de Lausanne.