Photos : © Bertrand Stofleth / La Salle de bains

Photos : © Bertrand Stofleth / La Salle de bains

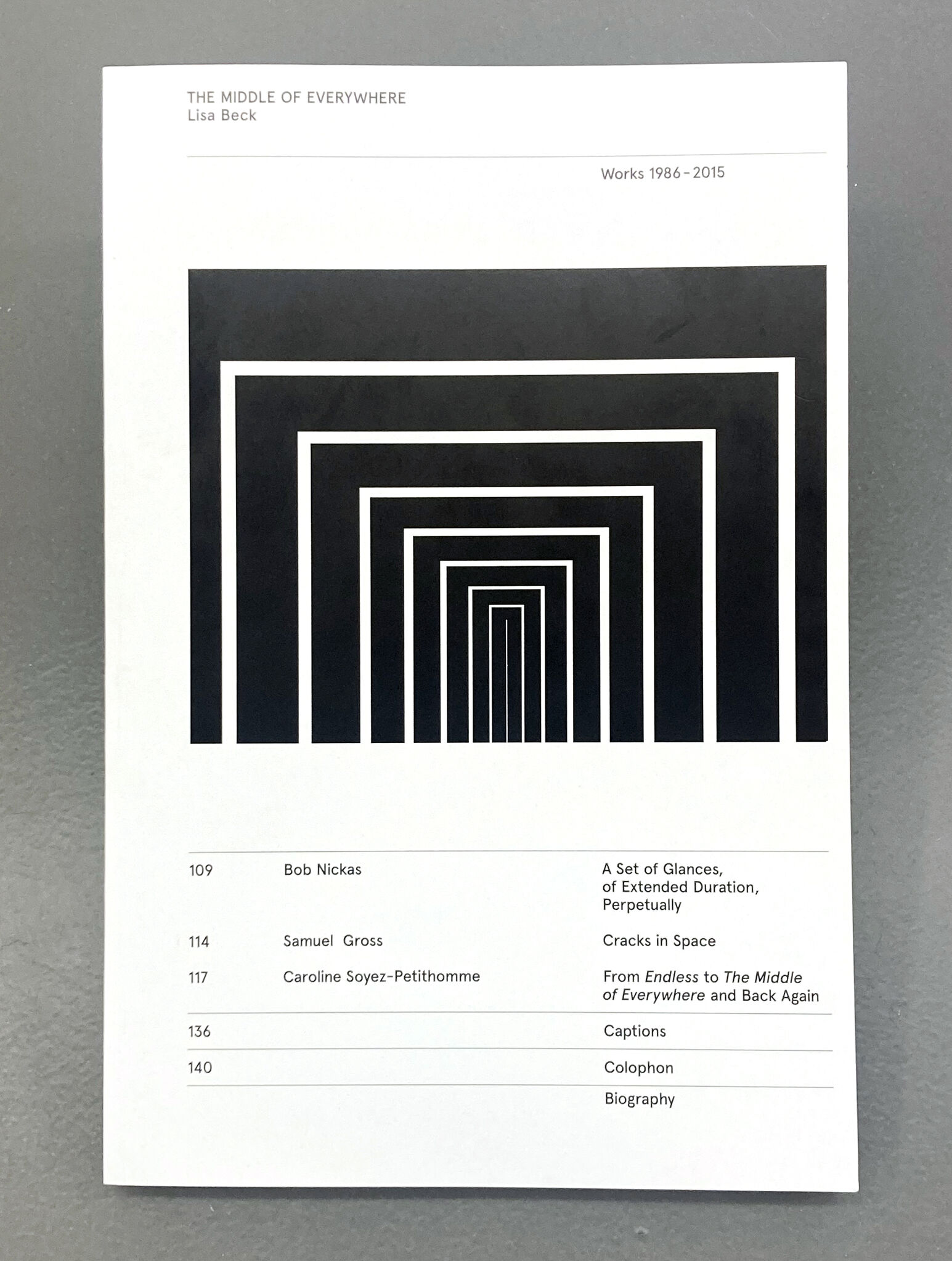

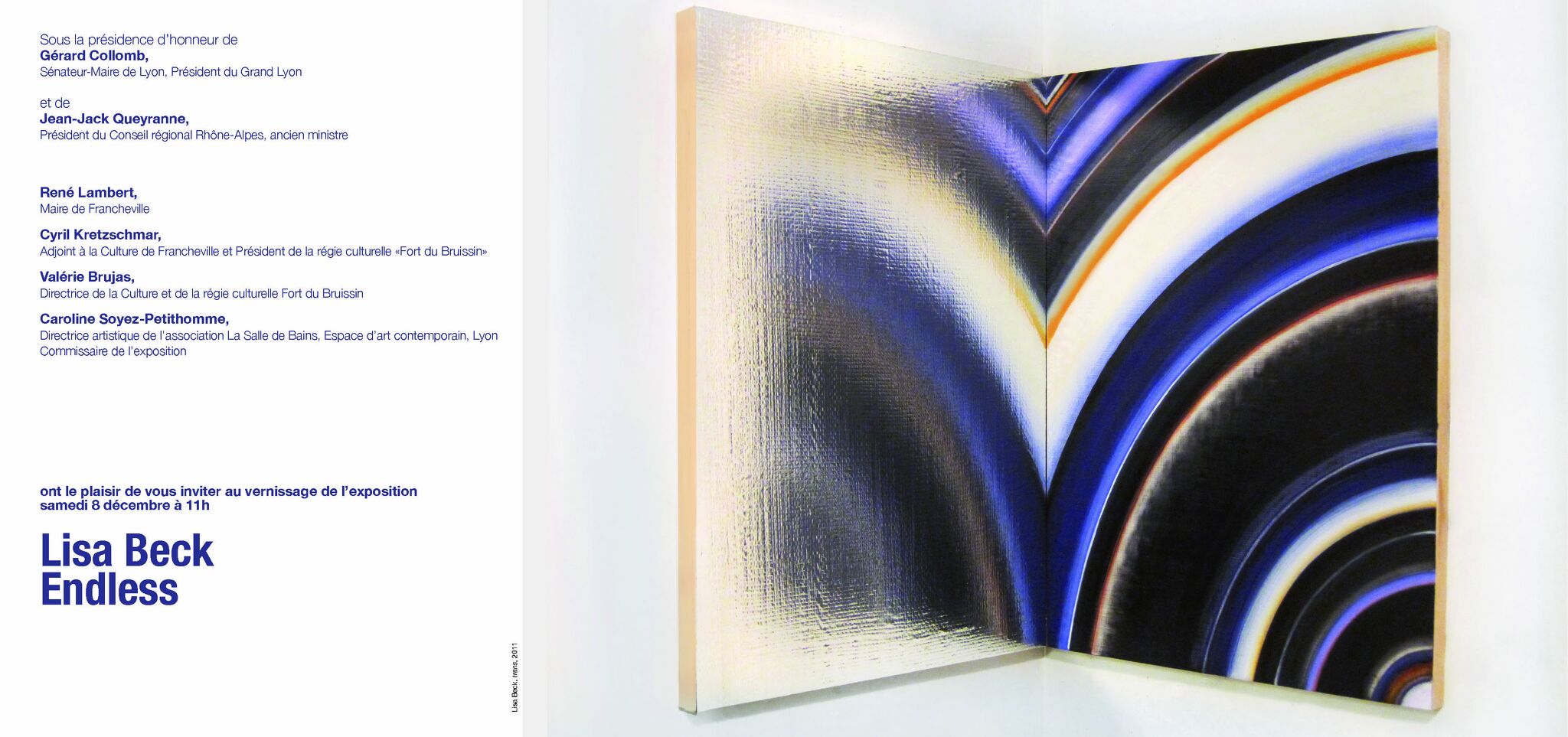

Endless

Du 8 décembre 2012 au 17 mars 2013From 8 December 2012 to 17 March 2013

Hors les murs → Fort du Bruissin

Pour sa dixième exposition, depuis sa réhabilitation, le Fort du Bruissin, centre d’art contemporain de Francheville a invité Caroline Soyez-Petithomme, directrice artistique de La Salle de bains, a concevoir un projet d’exposition d’un ou une artiste de son choix. Elle a choisi de présenter le travail de l’artiste américaine Lisa Beck et d’investir l’ensemble des espaces d’expositions du centre d’art contemporain.

Sa première exposition personnelle en France est l’occasion de rassembler une large sélection d’œuvres (peintures, installations et sculptures) et de faire dialoguer des productions datant du milieu des années 80 avec d’autres plus contemporaines, réalisées depuis 2010 dont certaines spécialement produites pour l’exposition «Endless» au Fort du Bruissin.

En amont des certitudes offertes par cette sélection d’œuvres demeurent un grand nombre d’imprévus. Entre le moment de la rédaction de ce texte et le vernissage de l’exposition, il est difficile d’imaginer ce qui adviendra en termes de contenu et de display. «Cela ne reste jamais comme c’était au début. Il y a toujours des ajustements, des accidents, et de nouvelles idées qui surgissent en cours de route, lorsque je travaille (1) », explique Lisa Beck.

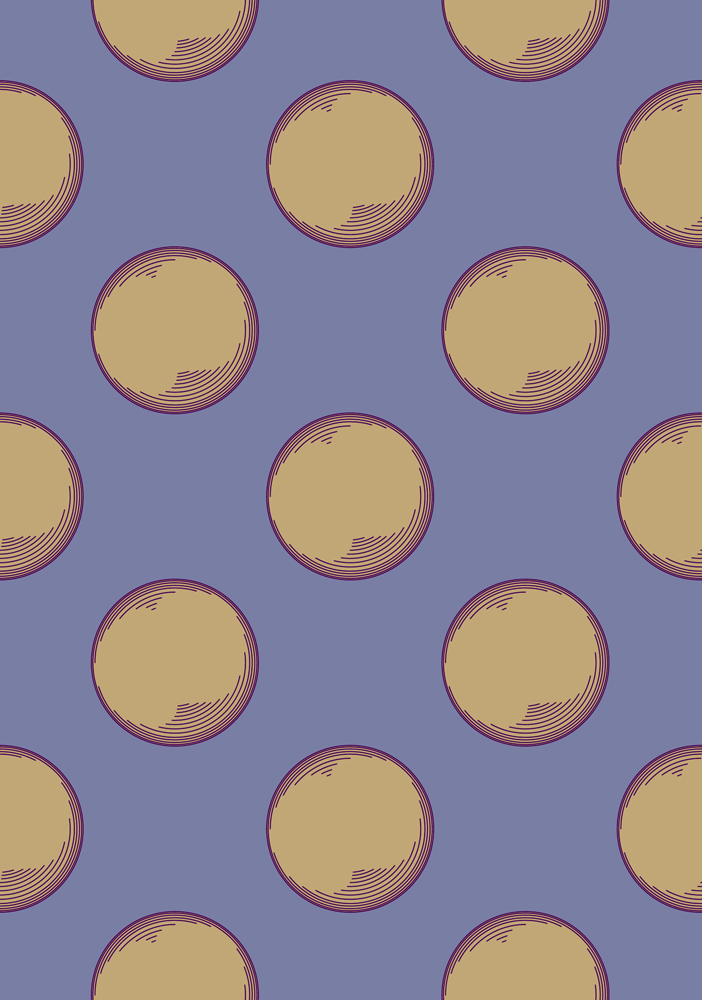

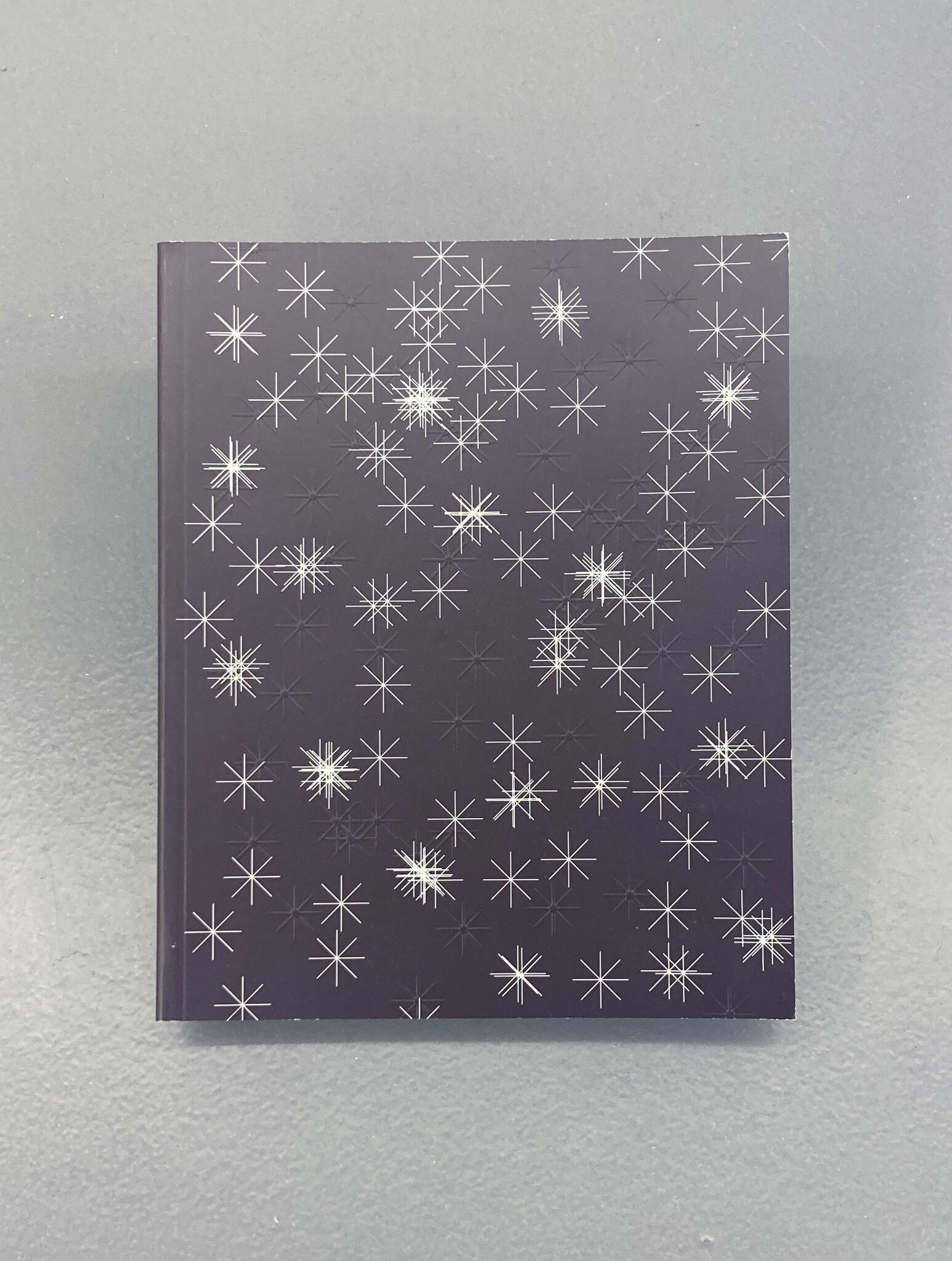

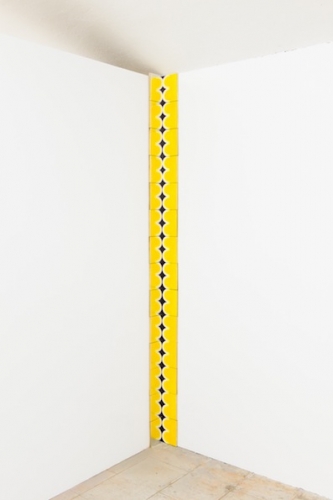

Ainsi, «Endless» s’inscrit à la suite des explorations mentale et conceptuelle que Beck mène sur l’idée d’une surface picturale infinie qui serait paradoxalement composée de et interrompue par l’espace entre les œuvres, c’est-à-dire par l’architecture autant que par l’air qui séparent les peintures, installations ou sculptures. «Les molécules, les étoiles, l’horizon, les nuages et les lacs (2) », telles sont les sources d’inspiration de l’artiste. À partir de cela, elle abstrait littéralement des formes, des couleurs et des structures créant des arrangements d’objets, de matériaux et de peintures dont les effets de rythme, de symétrie, de miroir, de reflets ou de transparence évoluent à chaque exposition. C’est à la Rhode Island School of Design (dont elle sort diplômée en 1980) que Beck a étudié la peinture, mais également la sculpture et le cinéma, ce qui lui a sans doute permis de ne pas restreindre ses processus de création et de production aux techniques picturales traditionnelles de la peinture (acrylique ou huile, sur toile, sur bois ou encore peinture murale). Depuis cette formation, Beck poursuit ses recherches et expérimentations sur l’abstraction au sens large du terme : inventant des motifs, s’appropriant certains autres via des sources aussi diverses que des images scientifiques (Unbroken Chain 6, 1985, Eclipse 1 et 4, 2011) des objets du quotidien ou des matériaux de bricolage (Horizon Black, 2010, Observer, 2012).

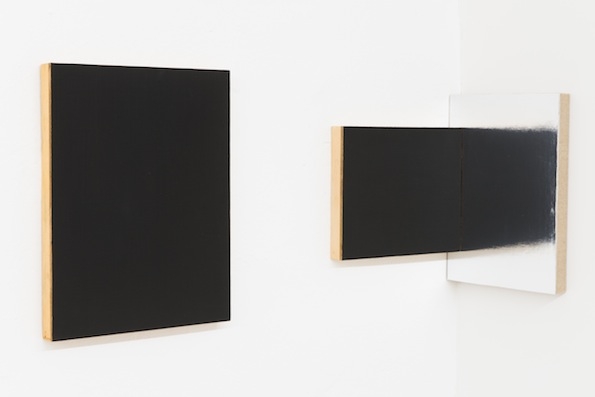

Les œuvres de Beck résultent de la combinaison de visions mentales et de ready-made (parfois assistés) articulant un corpus à la fois réflexif sur le médium de la peinture et résolument ouvert sur l’extérieur. Les œuvres incitent le visiteur — par le regard ou le déplacement physique — à considérer les bords de l’œuvre via les bordures évanescentes de certains motifs (The Shining Path, 1989) et enfin l’espace d’exposition lui- même (These VI, 2012, A Momentary Taste, 2012). Beck questionne ainsi le rapport que nous entretenons avec notre environnement spatial et visuel immédiat autant qu’avec l’Univers. Jouant sur la notion d’échelle et sur l’idée d’un espace de représentation réversible, sans endroit ni envers, elle multiplie l’usage des plans autres que le plan vertical selon lequel une peinture est traditionnellement accrochée au mur. Et ses sculptures aux surfaces transparentes ou réfléchissantes déconstruisent visuellement et mentalement les axes sol-plafond/murs. En somme, ces dernières déstabilisent l’espace tridimensionnel et notre habituelle déambulation autour de la sculpture

À l’instar des expériences psychédéliques relatées par Adolf Huxley dans Les Portes de la Perception (1954), Beck est obsédée par l’intrication des motifs, par le fait de regarder la réalité «en pur esthète qui se préoccupe uniquement des formes et de leurs relations dans le champ visuel et le cadre du tableau (3)», et par le fait de retranscrire l’expérience du «là-bas» ou «ici», ou dans les deux mondes, l’intérieur et l’extérieur, simultanément ou successivement (4)». Les expositions de Beck pourraient virtuellement être retournées sur l’envers : l’espace d’exposition ou l’architecture faisant partie intégrante des œuvres grâce à de multiples moyens techniques et effets d’optique.

Par exemple, les monochromes argentés (recouverts de «Mylar», matériau industriel utilisé notamment pour la culture botanique en milieu artificiel) réfléchissent les courbes vivement colorées des motifs répétitifs semi-circulaires évoquant les sillons d’un vinyle (rads, 2012) ou les modules infinis de la Colonne Sans Fin (1917) de Brancusi (Column, 2012). Certaines peintures sont reliées et suspendues par des câbles (Strophic Cascades, 1997, Informed, 1992), quelques petits miroirs peints (ready-made assistés) pendent également à un fil accroché au plafond (Cast, 2011). Les peintures sont tour à tour inclinées de différentes manières : accrochées en haut du mur, presque horizontalement de façon à ce que leurs surfaces peintes soient parfaitement visibles. Parfois, elles reposent plus simplement en bas du mur ou sont empilées, la face peinte orientée vers le sol laissant seul le dos visible— sont-elles en attente ou à considérer comme des objets à appréhender sans hiérarchie ou sens de lecture particulier ? (Eleven Untitled Details, 1991). La surface picturale — conçue comme un espace infini, comme un allover physique et mental — continue au-delà de notre champ de vision : les parties ou les surfaces intentionnellement cachées suggèrent cette continuité de l’autre côté du châssis, du mur ou du miroir. Les couleurs et les formes sont des motifs positifs, mais ils dépendent et apparaissent grâce aux espaces vierges, aux vides qu’ils laissent au milieu du motif ou sur son pourtour.

Comme l’explique l’artiste, «Pour moi, une oeuvre est une sélection qui s’opère au sein d’un continuum, comme un cliché photographique est un fragment figé dans le temps. Je veux toujours que l’on garde à l’esprit que c’est une possible solution que j’ai trouvée, mais qu’il en existe des millions d’autres (5)». Comme en physique quantique, tous les objets sont à la fois autonomes et liés les uns aux autres et chacun d’entre eux contient potentiellement l’ensemble des propriétés qui déterminera le résultat final. Cependant, avant qu’ils ne soient mis en relation et avant le moment précis de l’expérience et de la mesure, il est impossible de savoir si l’une des particules possède telle ou telle propriété. Dans la pratique de Beck, la disposition et le nombre d’éléments qui forment une oeuvre repose également sur un principe de relativité, ils peuvent être déplacés, adaptés à l’espace et ils demeurent interchangeables d’une exposition à l’autre. Ce continuum d’oeuvres constitue donc un ensemble de variations agencées en fonction des particularités architecturales, du dialogue avec le commissaire ou de l’humeur personnelle de l’artiste, comme lors d’une improvisation musicale ou théâtrale.

Une telle liberté artistique pourtant fondamentale et la flexibilité du statut de l’œuvre d’art qu’elle implique s’avère problématique si l’on considère la peinture selon le dogme de l’objet fini ou selon les méthodes de l’histoire ou du marché de l’art : ces deux domaines demandant des éléments stables ou, du moins, un archivage rigoureux enregistrant les différents états de ce flux permanent.

En outre, le travail de Beck livre les indices d’une accélération du tournant amorcé depuis les premières décennies du 20ème siècle par les avant-gardes modernistes. Celles-ci ont renouvelé le statut de la peinture par des accrochages non verticaux de la peinture (par exemple : la première exposition Suprématiste de Malevitch en 1915 avec le Carré noir sur fond blanc accroché dans l’angle de deux murs, le Cabinet Abstrait de Lissitzky (1927), Le Diagramme du Champ de Vision à 360° de Herbert Bayer (1935), la galerie The Art of this Century de Frederick Kiesler (1942)), l’incorporation des ready-made, l’ascension du monochrome et de la sérialité. Considérant cette grammaire, Beck utilise de façon récurrente des câbles pour relier ses peintures, les accrocher au mur ou les suspendre. Il est intéressant de souligner que les débuts de sa carrière sont concomitants de discours artistiques similaires concernant la peinture et ses à-côtés, et parmi eux celui de Martin Kippenberger qui considère que la peinture individuelle doit rendre explicitement visible son appartenance à un réseau : «Accrocher simplement une peinture sur un mur et prétendre que c’est de l’art est épouvantable. Tout le réseau est important! Même les spaghettini... À partir du moment où l’on prononce le mot «art», tout peut en faire partie. Dans une galerie, cela comprend également le sol, l’architecture, la couleur du mur (6)».

De ces démarches voisines, une autre question signifiante émerge : comment la peinture appartientelle à un réseau (à ce système sans début ni fin)? À la même période, au début des années quatre-vingt-dix, Beck commence à connecter ses peintures physiquement et à les faire se refléter les unes dans les autres. Ces solutions plastiques ne partent pas seulement à la rencontre des problématiques liées au cloisonnement des diverses catégories artistiques telles qu’elles furent soulevées par les avant-gardes modernistes au début du 20ème siècle et qui sont un siècle plus tard devenues quelque peu archétypales ou rhétoriques.

Les oeuvres de Beck ne se contentent pas de défier l’histoire ou les stratégies du marché de l’art. Elles enchérissent sur l’inépuisable reproductibilité de l’oeuvre et de façon plus contemporaine sur l’ubiquité de l’oeuvre induite par Internet et la technologie numérique. L’artiste précise que l’analogie est avant tout conceptuelle et métaphorique: «L’oeuvre d’art comme réseau est l’expression ou le miroir de la formation de l’esprit, de la façon dont nous élaborons des motifs répétitifs à partir de l’apparente entropie de l’expérience (7)».

As suggested with the exhibition title “Endless”, Lisa Beck’s art practice unfolds as a continuum and as an open-ended series of (mainly abstract) patterns the artist has been invting, repeating and displaying since the mid of the 80s.

Lisa Beck’s first solo exhibition in France is the occasion to gather a wide selection of various types of paintings, installations and sculptures, and also early paintings and installations made in the mid-80s and 90s in dialogue with her recent pieces, includind the newest works produced especially for the art centre of the Fort du Bruissin. However, beside the certainties of those already selected works, it is almost impossible to predict what will really happen in-between the moment this press release is being written, and the time the exhibition is installed, in terms of display and content — one of the artist’s main statements being: “It never stays the way it starts. There are always adjustments, accidents, and new ideas that pop up while I am working.” (1)

Thus, “Endless” follows Beck’s exploration of a mentally and conceptually infinite surface, which is paradoxically made of, as well as interrupted by, the space in-between the works, the architecture and the air. “Molecules, stars, horizons, clouds and lakes” (2) is what the artist has always at the back of her mind when she works. And from that she literally abstracts forms, colours, and structures to create evolving rhythmic, symmetric, mirroring or transparent arrangements of objects, materials and paintings.

At the Rhode Island School of Design (where she graduated in 1980), Lisa Beck studied painting, but also film and sculpture. Her creation process as well as the media she uses are in no way restrained to the use of traditional techniques like acrylic or oil on canvas, wooden panel, or wall. Since then, Beck has been searching and experimenting abstraction in its broadest sense : inventing patterns, appropriating some existing ones from a wide range of sources from scientific imagery (Unbroken Chain 6, 1985, Eclipse 1 and Eclipse 4, 2011) to everyday, arts and crafts or DIY objects (Horizon Black, 2012, Observer, 2012).

Beck’s works result both from this combination of mental visions and (sometimes assisted) ready-made objects and patterns, so that this corpus is self-reflexive about the medium of the painting itself and at the same time resolutely and physically leads the viewer’s glance to the outside: to the edges of a painting or of the evanescent pattern (The Shining Path, 1989), and to the exhibition space itself (These VI, 2012, A Monumentary Taste, 2012). The artist aims to question our relationship to the close spatial and visual environment, as well as to the Universe. Playing with scale and the use of upside down representational space, she breaks the common vertical or orthogonal plan within which we usually contemplate a painting hung on the wall or walk around a sculpture whose surface is neither transparent nor mirroring.

Like the psychedelic experiences described in Adolf Huxley’s The Doors of Perception (1954), Beck has been obsessed with intricate patterns, with looking at the reality “ as a pure aesthete whose concern is only with forms and their relationships within the field of vision or the picture space” (3); and with transcribing the experience of “the ‘out there,’ or ‘in here,’ or in both worlds, the inner and the outer, simultaneously or successively.” (4) For that reason Beck’s exhibitions can potentially be turned inside out. The surroundings and the architecture are always part of the works and involved in manifold technical means and optical effects. For instance: some silver reflective monochromes hung on one wall of a corner reflect colourful rainbows and repetitive patterns hung on the adjacent wall (Column, 2012, Rads, 2012). Some paintings are linked together and/or suspended with wires (Strophic Cascades, 1997, Informed, 1992), and few painted hand-mirrors (ready-made) are also suspended from the ceiling (Cast, 2011). Some of the paintings are leaning out from the top of the wall, bending against the wall or laying down, as a stack, their supposed painted face on the ground (Eleven Untitled Details, 1991). Their pictorial surface — conceived as an infinite space, as a physical and mental all over — continue beyond our field of vision, beyond its visibility: on the intentionally hidden surface or on the other side of the wall, or on the other side of the mirror. Therefore, colors and forms — like positive patterns — are as important as the voids, the blank spaces or negative forms left in the middle and around them.

As Beck explains, “ For me, an artwork is a selection out of a continuum, like a snapshot is a piece of stopped time. I always want to acknowledge that, to say: this is what I’ve come up with, but there are a million other ways it could exist.” (5) As in the realm of Quantum Physics, all the objects are related to each other and each of them potentially contains all the properties that will determine the final result. However, before they are put in relation to each other and before this precise instant it is impossible to know which one of the particles has any particular property. In Beck’s practice the placement or number of paintings or elements within a piece is a matter of relativity, as they may shifted, adapting to the space, and they remain changeable for subsequent exhibitions. The corpus of works she has been creating since the 90s consists of a continuous set of variations the artist displays according to the dialogue with the curator, to the architectural features as well as to the artist’s mood, like a musical or theatrical improvisation.

Such a fundamental artistic freedom and the flexible status of the artwork is challenging regarding the conception of painting as a finite object — and this can be troublesome especially for the art historian or for the art market, from a commercial point of view: both those fields requiring stable elements or at least a rigorous archival method to record the different states of this permanent flux.

Moreover, Beck’s work gives off the clues of the strong shift of the attitudes of the modernist avant-gardes in the first decades of the 20th Century which renewed the status of painting through various non-vertical displays of paintings (for instance: Malevich’s First Suprematist Exhibition in 1915, featuring Black Square hanging in the corner, El Lissitzky’s Abstract Cabinet (1927), Hebert Bayer’s Diagram of 360 Degrees Field of Vision (1935), Frederick Kiesler’s Art of this Century gallery (1942)), the incorporation of readymades, the rise of the monochrome, seriality and the gestural techniques of dripping, pouring, and staining. And besides that grammar, since the 90s, Beck has recurrently used wires to link paintings together, or to hang them from the walls or from the ceiling. Her early artistic developments were concomitant with German artist Martin Kippenberger’s claims regarding individual paintings which should be explicitly visualized as networks: “Simply to hang a painting on the wall and say that it’s art is dreadful. The whole network is important! Even spaghettini . . . When you say art, then everything possible belongs to it. In a gallery that is also the floor, the architecture, the color of the walls.” (6)

Coincidentally or in the Zeitgeist of this period, Beck started working with a similar attitude. She also started connecting paintings with each other and having them reflect each other. From that and from Kippenberger’s statement, another significant question arises: How does painting belong to a network (to an endless system)? In that sense, Beck’s practice meets not only the archetypal issues of the modernist avant-gardes about painting, she not only challenges the art historical methods, and art market strategy, but also references mechanical reproduction and the ubiquity of digital networks. And as the artist explains: “The artwork as network is an expression or mirror of the formation of meaning in the mind as it constructs repetitive patterns from the randomness of experience”. (7)

Lisa Beck’s first solo exhibition in France is the occasion to gather a wide selection of various types of paintings, installations and sculptures, and also early paintings and installations made in the mid-80s and 90s in dialogue with her recent pieces, includind the newest works produced especially for the art centre of the Fort du Bruissin. However, beside the certainties of those already selected works, it is almost impossible to predict what will really happen in-between the moment this press release is being written, and the time the exhibition is installed, in terms of display and content — one of the artist’s main statements being: “It never stays the way it starts. There are always adjustments, accidents, and new ideas that pop up while I am working.” (1)

Thus, “Endless” follows Beck’s exploration of a mentally and conceptually infinite surface, which is paradoxically made of, as well as interrupted by, the space in-between the works, the architecture and the air. “Molecules, stars, horizons, clouds and lakes” (2) is what the artist has always at the back of her mind when she works. And from that she literally abstracts forms, colours, and structures to create evolving rhythmic, symmetric, mirroring or transparent arrangements of objects, materials and paintings.

At the Rhode Island School of Design (where she graduated in 1980), Lisa Beck studied painting, but also film and sculpture. Her creation process as well as the media she uses are in no way restrained to the use of traditional techniques like acrylic or oil on canvas, wooden panel, or wall. Since then, Beck has been searching and experimenting abstraction in its broadest sense : inventing patterns, appropriating some existing ones from a wide range of sources from scientific imagery (Unbroken Chain 6, 1985, Eclipse 1 and Eclipse 4, 2011) to everyday, arts and crafts or DIY objects (Horizon Black, 2012, Observer, 2012).

Beck’s works result both from this combination of mental visions and (sometimes assisted) ready-made objects and patterns, so that this corpus is self-reflexive about the medium of the painting itself and at the same time resolutely and physically leads the viewer’s glance to the outside: to the edges of a painting or of the evanescent pattern (The Shining Path, 1989), and to the exhibition space itself (These VI, 2012, A Monumentary Taste, 2012). The artist aims to question our relationship to the close spatial and visual environment, as well as to the Universe. Playing with scale and the use of upside down representational space, she breaks the common vertical or orthogonal plan within which we usually contemplate a painting hung on the wall or walk around a sculpture whose surface is neither transparent nor mirroring.

Like the psychedelic experiences described in Adolf Huxley’s The Doors of Perception (1954), Beck has been obsessed with intricate patterns, with looking at the reality “ as a pure aesthete whose concern is only with forms and their relationships within the field of vision or the picture space” (3); and with transcribing the experience of “the ‘out there,’ or ‘in here,’ or in both worlds, the inner and the outer, simultaneously or successively.” (4) For that reason Beck’s exhibitions can potentially be turned inside out. The surroundings and the architecture are always part of the works and involved in manifold technical means and optical effects. For instance: some silver reflective monochromes hung on one wall of a corner reflect colourful rainbows and repetitive patterns hung on the adjacent wall (Column, 2012, Rads, 2012). Some paintings are linked together and/or suspended with wires (Strophic Cascades, 1997, Informed, 1992), and few painted hand-mirrors (ready-made) are also suspended from the ceiling (Cast, 2011). Some of the paintings are leaning out from the top of the wall, bending against the wall or laying down, as a stack, their supposed painted face on the ground (Eleven Untitled Details, 1991). Their pictorial surface — conceived as an infinite space, as a physical and mental all over — continue beyond our field of vision, beyond its visibility: on the intentionally hidden surface or on the other side of the wall, or on the other side of the mirror. Therefore, colors and forms — like positive patterns — are as important as the voids, the blank spaces or negative forms left in the middle and around them.

As Beck explains, “ For me, an artwork is a selection out of a continuum, like a snapshot is a piece of stopped time. I always want to acknowledge that, to say: this is what I’ve come up with, but there are a million other ways it could exist.” (5) As in the realm of Quantum Physics, all the objects are related to each other and each of them potentially contains all the properties that will determine the final result. However, before they are put in relation to each other and before this precise instant it is impossible to know which one of the particles has any particular property. In Beck’s practice the placement or number of paintings or elements within a piece is a matter of relativity, as they may shifted, adapting to the space, and they remain changeable for subsequent exhibitions. The corpus of works she has been creating since the 90s consists of a continuous set of variations the artist displays according to the dialogue with the curator, to the architectural features as well as to the artist’s mood, like a musical or theatrical improvisation.

Such a fundamental artistic freedom and the flexible status of the artwork is challenging regarding the conception of painting as a finite object — and this can be troublesome especially for the art historian or for the art market, from a commercial point of view: both those fields requiring stable elements or at least a rigorous archival method to record the different states of this permanent flux.

Moreover, Beck’s work gives off the clues of the strong shift of the attitudes of the modernist avant-gardes in the first decades of the 20th Century which renewed the status of painting through various non-vertical displays of paintings (for instance: Malevich’s First Suprematist Exhibition in 1915, featuring Black Square hanging in the corner, El Lissitzky’s Abstract Cabinet (1927), Hebert Bayer’s Diagram of 360 Degrees Field of Vision (1935), Frederick Kiesler’s Art of this Century gallery (1942)), the incorporation of readymades, the rise of the monochrome, seriality and the gestural techniques of dripping, pouring, and staining. And besides that grammar, since the 90s, Beck has recurrently used wires to link paintings together, or to hang them from the walls or from the ceiling. Her early artistic developments were concomitant with German artist Martin Kippenberger’s claims regarding individual paintings which should be explicitly visualized as networks: “Simply to hang a painting on the wall and say that it’s art is dreadful. The whole network is important! Even spaghettini . . . When you say art, then everything possible belongs to it. In a gallery that is also the floor, the architecture, the color of the walls.” (6)

Coincidentally or in the Zeitgeist of this period, Beck started working with a similar attitude. She also started connecting paintings with each other and having them reflect each other. From that and from Kippenberger’s statement, another significant question arises: How does painting belong to a network (to an endless system)? In that sense, Beck’s practice meets not only the archetypal issues of the modernist avant-gardes about painting, she not only challenges the art historical methods, and art market strategy, but also references mechanical reproduction and the ubiquity of digital networks. And as the artist explains: “The artwork as network is an expression or mirror of the formation of meaning in the mind as it constructs repetitive patterns from the randomness of experience”. (7)

1. Lisa Beck in «Q&A» with Hudson for the exhibition «To Everything», Feature Inc., New York, June 2009», in Lisa Beck: Yes, No, Something, Nothing, Never, Always, Feature Inc. Publishing, New York, 2012, p42: «It never stays the way it starts. There are always adjustments, accidents, and new ideas that pop up white I am working.» (Les traductions sont celles de Caroline Soyez-Petithomme, sauf précision contraire).

2. Idem, p 42 : «Molécules, stars, horizons, clouds and lake.»

3. Adolf Huxley, Les Portes de la Perception, traduit de l’anglais par Jules Castier, 10/18 éditions du Rochers, 1954, pp 25-26.

4. Idem, pp 30-31.

5. «Lisa Beck interviewed by Bob Nickas», in Lisa Beck: Yes, No, Something, Nothing, Never, Always, Feauture Inc. Publishing, New York, 2012, p4 : «For me, an artwork is a selection out of a continuum, like a snapshot is a piece of stopped time. I always want to acknowledge that, to say : this is what I’ve come up with, but there are a million other ways it could exist.»

6. Martin Kippenberger in «One Has to Be Able to Take It!», an interview with Martin Kippenberger by Jutta Koether, November 1990-May 1991, in Martin Kippenberger : The Problem Perspective, edited by Ann Goldstein, The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles and MIT Press, Cambridge, 2008, p316 : «Simply to hang a painting on the wall and say that it’s art is dreadful. The whole network is important! Even spaghettini... When you say art, then everything possible belongs to it. In a gallery that is also the floor, the architecture, the color of the wall».

7. Lisa Beck, email conversation with Caroline Soyez-Petithomme, on October the 23rd 2012 : «The artwork as network is

an expression or mirror of the formation of meaning in the mind as it constructs repetitive patterns from the seeming randomness of experience».

2. Idem, p 42 : «Molécules, stars, horizons, clouds and lake.»

3. Adolf Huxley, Les Portes de la Perception, traduit de l’anglais par Jules Castier, 10/18 éditions du Rochers, 1954, pp 25-26.

4. Idem, pp 30-31.

5. «Lisa Beck interviewed by Bob Nickas», in Lisa Beck: Yes, No, Something, Nothing, Never, Always, Feauture Inc. Publishing, New York, 2012, p4 : «For me, an artwork is a selection out of a continuum, like a snapshot is a piece of stopped time. I always want to acknowledge that, to say : this is what I’ve come up with, but there are a million other ways it could exist.»

6. Martin Kippenberger in «One Has to Be Able to Take It!», an interview with Martin Kippenberger by Jutta Koether, November 1990-May 1991, in Martin Kippenberger : The Problem Perspective, edited by Ann Goldstein, The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles and MIT Press, Cambridge, 2008, p316 : «Simply to hang a painting on the wall and say that it’s art is dreadful. The whole network is important! Even spaghettini... When you say art, then everything possible belongs to it. In a gallery that is also the floor, the architecture, the color of the wall».

7. Lisa Beck, email conversation with Caroline Soyez-Petithomme, on October the 23rd 2012 : «The artwork as network is

an expression or mirror of the formation of meaning in the mind as it constructs repetitive patterns from the seeming randomness of experience».

1. Lisa Beck in “Q&A” with Hudson for the exhibition “To Everything”, Feature Inc., New York, June 2009”, in Lisa Beck: Yes, No, Something, Nothing, Never, Always, Feature Inc. Publishing, New York, 2012, p 42.

2. Idem, p 42.

3. Adolf Huxley, The Doors of Perception, 1954, Harper Collins Publishers, New York, 2009, pp 21-22.

4. Idem, pp 25-26.

5. «Lisa Beck interviewed by Bob Nickas», dans Lisa Beck: Yes, No, Something, Nothing, Never, Always, Feauture Inc. Publishing, New York, 2012, p4.

6. Martin Kippenberger in «One Has to Be Able to Take It!», an interview with Martin Kippenberger by Jutta Koether, November 1990-May 1991, in Martin Kippenberger : The Problem Perspective, edited by Ann Goldstein, The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles and MIT Press, Cambridge, 2008, p.316.

7. Lisa Beck, email conversation with Caroline Soyez-Petithomme, on October the 23rd 2012.

2. Idem, p 42.

3. Adolf Huxley, The Doors of Perception, 1954, Harper Collins Publishers, New York, 2009, pp 21-22.

4. Idem, pp 25-26.

5. «Lisa Beck interviewed by Bob Nickas», dans Lisa Beck: Yes, No, Something, Nothing, Never, Always, Feauture Inc. Publishing, New York, 2012, p4.

6. Martin Kippenberger in «One Has to Be Able to Take It!», an interview with Martin Kippenberger by Jutta Koether, November 1990-May 1991, in Martin Kippenberger : The Problem Perspective, edited by Ann Goldstein, The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles and MIT Press, Cambridge, 2008, p.316.

7. Lisa Beck, email conversation with Caroline Soyez-Petithomme, on October the 23rd 2012.

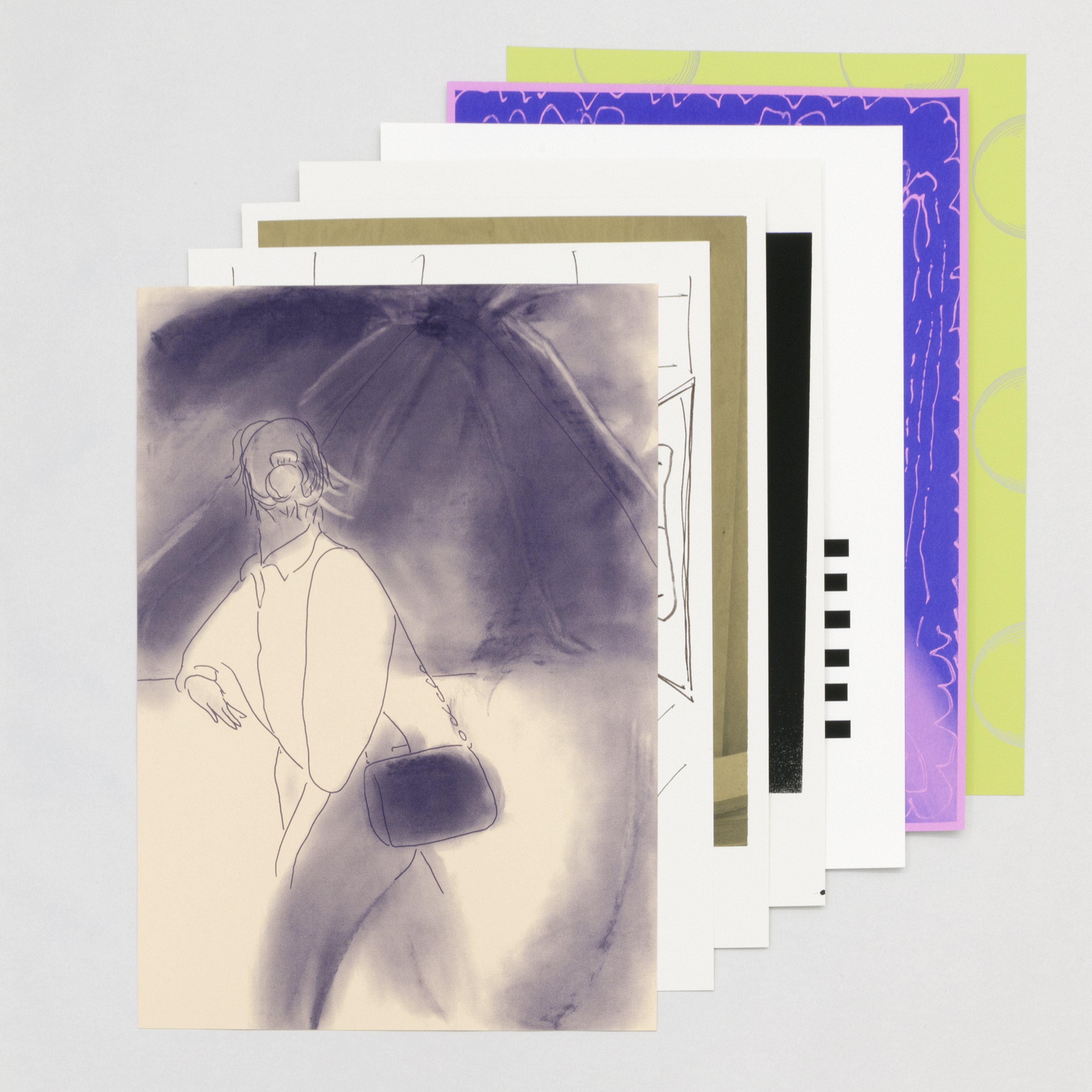

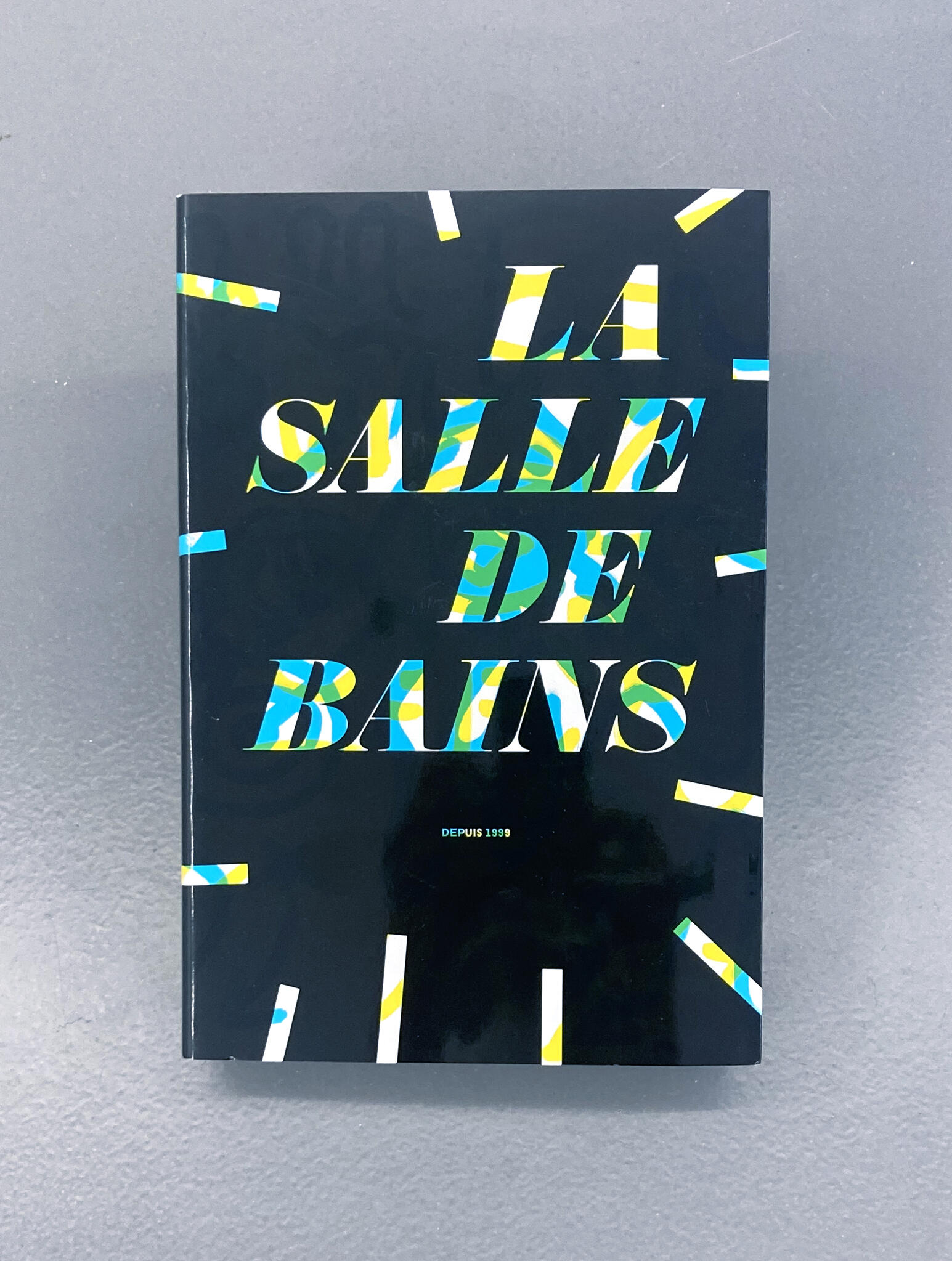

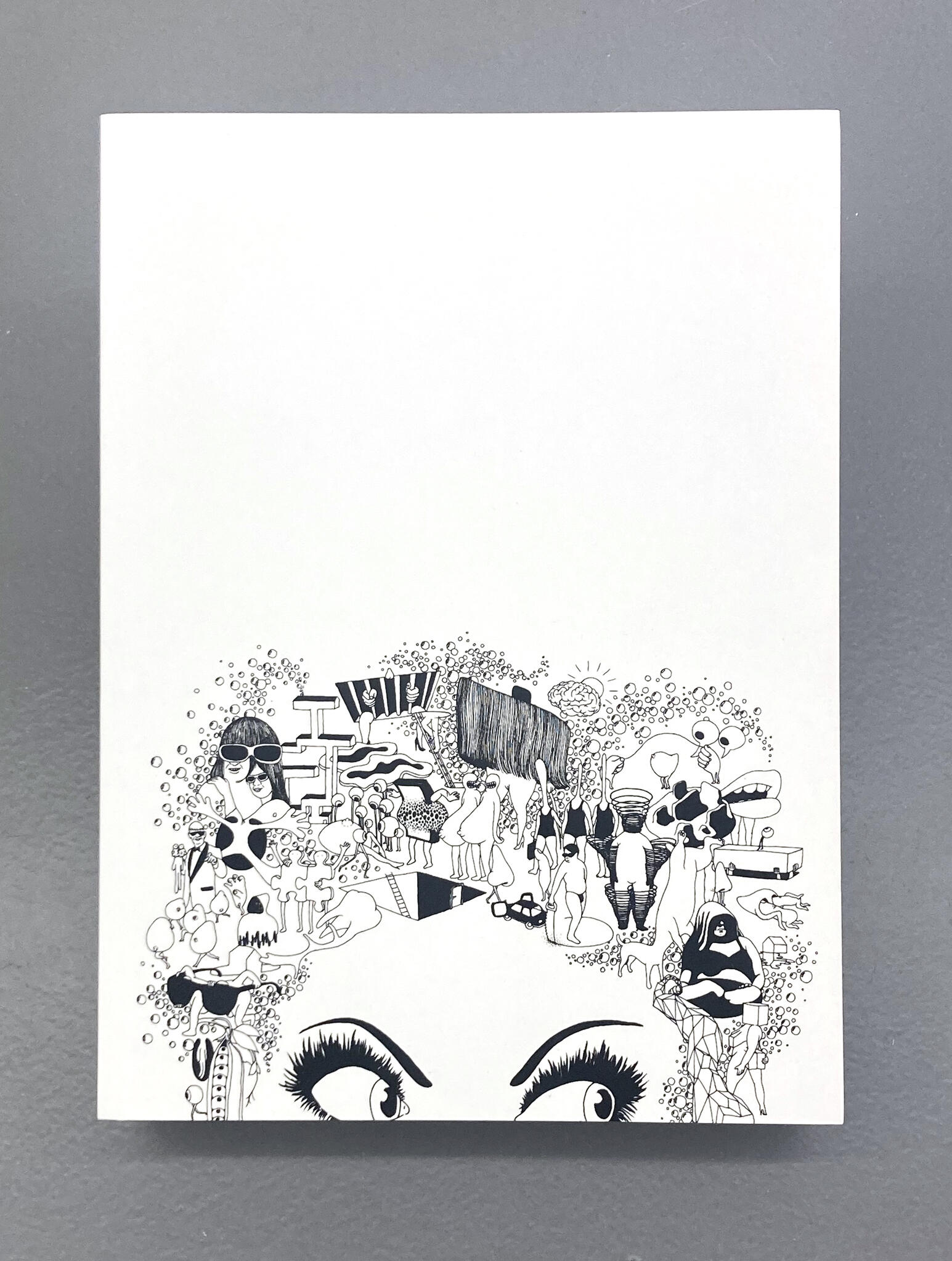

Endless, 2012

carton d'invitation

Lisa Beck, née en 1958 (USA).

Vit et travaille à NYC.

Représentée par Feature Inc. et Lisa Ruyter.

Vit et travaille à NYC.

Représentée par Feature Inc. et Lisa Ruyter.

Lisa Beck, née en 1958 (USA).

Vit et travaille à NYC.

Représentée par Feature Inc. et Lisa Ruyter.

Vit et travaille à NYC.

Représentée par Feature Inc. et Lisa Ruyter.

L’exposition Endless de Lisa Beck est un partenariat entre Le Fort du Bruissin (producteur de l'exposition) et La Salle de bains (commissariat par Caroline Soyez-Petithomme).

Le Fort du Bruissin est financé par la ville de Francheville et la région Rhône-Alpes.

Le Fort du Bruissin est financé par la ville de Francheville et la région Rhône-Alpes.

L’exposition Endless de Lisa Beck est un partenariat entre Le Fort du Bruissin (producteur de l'exposition) et La Salle de bains (commissariat par Caroline Soyez-Petithomme).

Le Fort du Bruissin est financé par la ville de Francheville et la région Rhône-Alpes.

Le Fort du Bruissin est financé par la ville de Francheville et la région Rhône-Alpes.

La Salle de bains reçoit le soutien du Ministère de la Culture DRAC Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes,

de la Région Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes et de la Ville de Lyon.

de la Région Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes et de la Ville de Lyon.