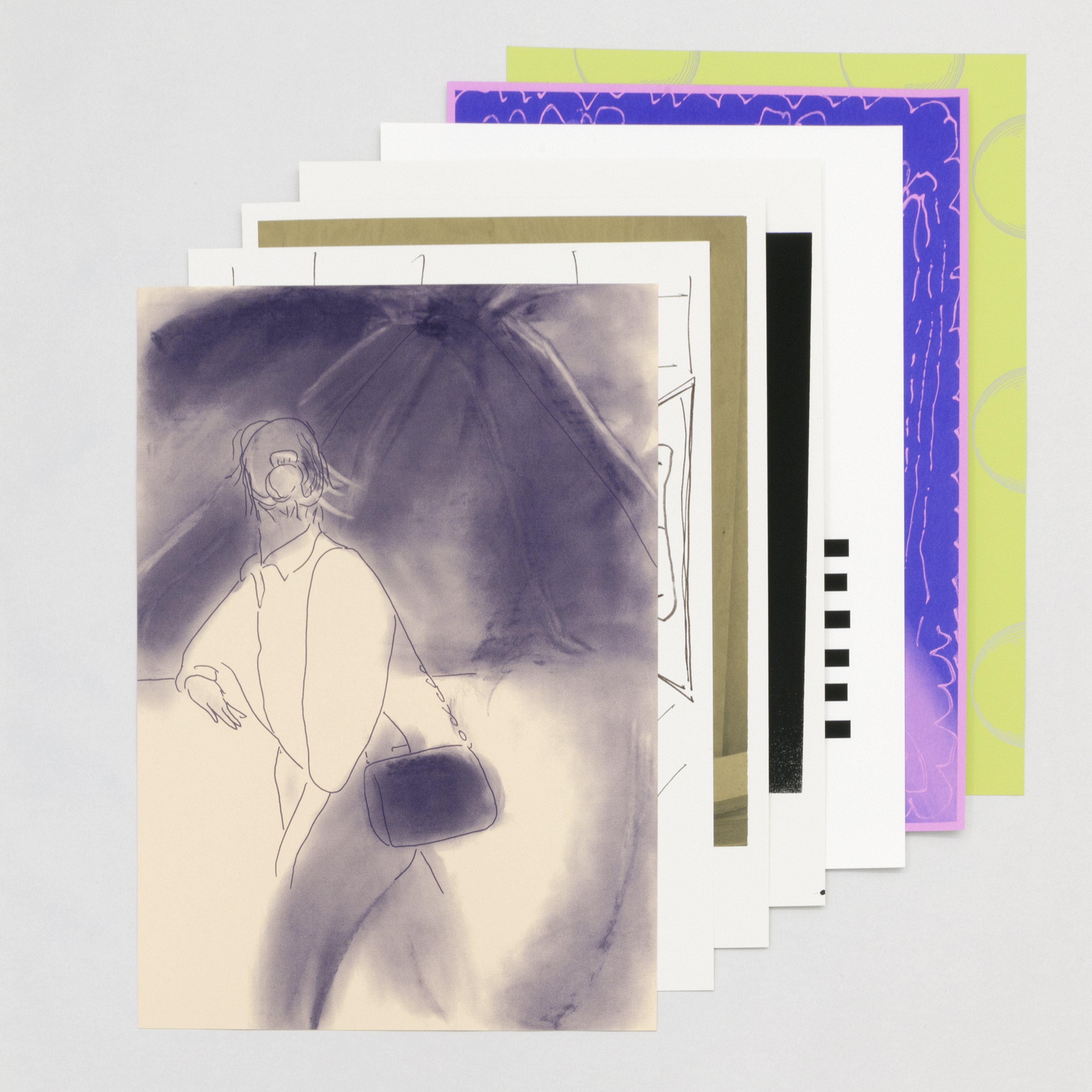

David Evrard, Mathis Gasser, Space Soap Strange Hypnosis Opera, vues d'exposition, la Salle de bains, Lyon, 2013. Photos : Aurélie Leplatre

David Evrard, Mathis Gasser, Space Soap Strange Hypnosis Opera, exhibtion views, la Salle de bains, Lyon, 2013. Photos: Aurélie Leplatre

Space Soap Strange Hypnosis Opera

Du 7 juin au 13 juillet 2013From 7 June to 13 July 2013

Space Soap Strange Hypnosis Opera est le titre commun aux deux expositions personnelles qui se tiennent en même temps à La Salle de bains, celle de David Evrard (BE) et celle de Mathis Gasser (CH).

“J'aime vraiment la culture en général, explique David Evrard, c'est pour cette raison que je m'intéresse à tous ces trucs, autant à la paysannerie qu'aux groupuscules anarchistes, aux comics ou à Faulkner, Flaubert, et Mallarmé.” Son exposition est ainsi un condensé d'obsessions culturelles très personnelles, de formes récupérées, et de produits d'expériences improvisées qui s'accumulent généreusement.Mathis Gasser montre pour la première fois des œuvres appartenant à The Alien Project, notamment une nouvelle série d'une vingtaine de peintures. Ce projet, entamé en 2012, porte l'impact que la découverte potentielle d'êtres extraterrestres pourrait avoir. L'alien sort ainsi du contexte cinématographique pour devenir une créature de pensée, permettant d'élaborer de nouvelles manières d'envisager ce que serait l'Autre, et le futur sur le vaisseau spatial terrien.

Communiqué de presse David Evrard :

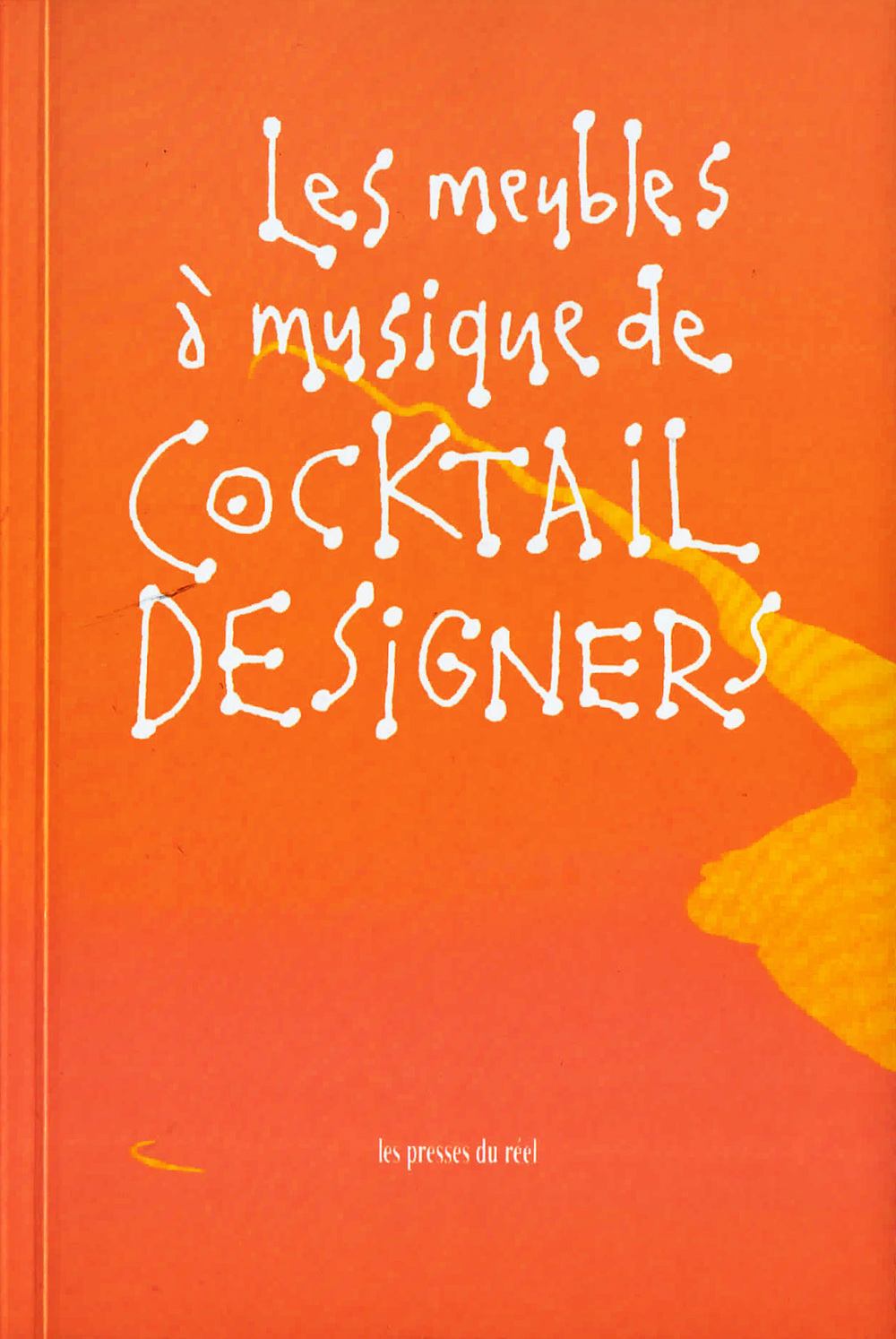

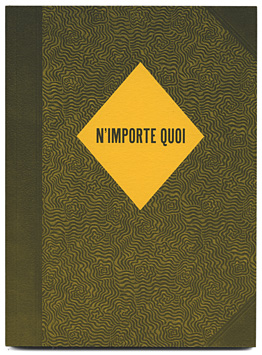

On ne peut malheureusement pas mettre l’univers tout entier dans un communiqué de presse. Mais puisqu’il faut bien donner quelques informations précises et quelques clefs de lecture aux visiteurs venus découvrir son exposition, commençons par dire que David Evrard est un artiste et auteur belge, qu’après avoir grandi à Liège, il s’est installé à Bruxelles, qu’il est le roi de la technique mixte (sculpture, photographie, collage, écriture, peinture), et que l’on retrouve cet éclatement dans l’exposition (un poster encadré des Stray Cats, des grandes affiches murales représentant des images génériques de paradis tropicaux, des aquarelles de pizza, une grande tapisserie, des sculptures, une impression sur toile). La source de ces objets est indifférente : certains sont récupérés et légèrement modifiés, d’autres sont utilisés comme des ready-mades, d’autres sont issus de commandes, et d’autres, enfin, sont réalisés par l’artiste. L’association de toutes ces choses est marquée par un rapport très fort à l’improvisation, un processus qui est devenu central pour l’artiste après un bref stage avec John Cage au Conservatoire de Liège au tout début des années 1990. Ce qui importe est donc moins ce que chaque objet en soi viendrait dire d’un savoir-faire, d’une technique propre aux artistes, que leur capacité respective à rendre visible leur origine et leur mode de production, et à créer volontairement une forme de désordre. Dans le travail de David Evrard, générosité fait loi. Générosité d’images et de formes accumulées (le hamburger et la pizza sont deux des modèles pratiques, explique-t-il, pour des sculptures en couches, modèles que l’on retrouve dans l’exposition). Générosité de références, et aussi de bonnes histoires (si vous aimez en secret un artiste américain à succès, une conservatrice du patrimoine française qui a été commissaire de l’une des dernières Documenta, le fils d’un peintre célèbre des 80’s devenu cinéaste, un prix Nobel de chimie belge d’origine russe, ou une bassiste-guitariste-chanteuse du groupe de rock indé le plus célèbre du monde, sachez que David Evrard a déjà passé une soirée avec elle ou avec lui). « J’aime vraiment la culture en général, explique-t-il, c’est pour cette raison que je m’intéresse à tous ces trucs, autant la paysannerie, que des groupuscules anarchistes, que des comics ou Faulkner, Flaubert, Mallarmé. Le dernier livre que je viens de terminer c’est Assassin Creeds, il a été écrit après le jeu vidéo et je me posais vraiment, en le lisant, la question de l’ekphrasis... ». Par ces mélanges de références, de matériaux, de sources, il ne cherche pas à mettre tous les objets culturels au même niveau. Ce qui l’intéresse est de se frayer son propre chemin à travers la culture, et de rendre compte de ses relations forcément amoureuses, et toujours riches d’enthousiasme, avec ses produits.

L’exposition pointe ainsi dans la direction du fan art (l’art des fans) avec la tapisserie Die Antwoord (un groupe de hip hop zef sud-africain), ou le portrait des Stray Cats, qui s’identifièrent eux-mêmes tellement à la position du fan qu’ils reproduisirent dans leur musique et dans leur look un univers musical vieux de plus de vingt ans. Formés à la fin des années 1970 dans l’état de New York, ils s’exilèrent rapidement à Londres où ils rencontrèrent le succès, avec un style rockabilly précis (ils avaient la même guitare qu’Eddie Cochran, une Gretsch 6120 orange). Les Stray Cats sont en quelque sorte les mascottes de l’exposition, ils sont « à la fois super ringards et super magnifiques », ils incarnent, explique l’artiste, une « ringardise épique ». La posture du fan (de musique, de mythologie pop, d’art contemporain, de films de zombies, de psychobilly, de kitsch, ou de toutes les possibles constellations culturelles...), comprise comme une manière productive de digérer le capitalisme et ses produits, pourrait ainsi être un bon modèle pour comprendre les accumulations opérées par l’artiste.

Son travail se nourrit aussi d’une réflexion sur la récupération. Et c’est dans ce processus -s’appuyer sur des choses précaires ou mal aimées pour les remettre en circulation et leur offrir une légitimité – que réside la charge politique de son travail. L’artiste met d’ailleurs cette précarité en rapport avec son histoire personnelle : il a grandi dans la banlieue de Liège, et appartient à une génération pour qui la banlieue, dit-il, est devenue un genre en soi, quelque chose de marginal et déclassé, qui se revendique désormais pour lui-même. Il a le même âge, rappelle-t-il, que Joey Starr ou Tricky, avec qui il a réalisé un entretien, publié en 2011 dans le premier numéro de la revue YEAR (publiée par Komplot, non-profit space bruxellois créé et dirigé par Sonia Dermience, et dont David Evrard est un actif membre).

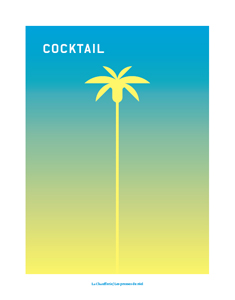

Son travail aborde heureusement ces questions sans didactisme, c’est-à-dire dans les formes mêmes (elles portent les traces de leur fabrication, de leur circulation, de leur élévation) et dans une forme d’humour assumé. Après tout, David Evrard est le genre d’artiste qui accroche des pizzas dans les palmiers.

David Evrard tient à remercier Nadine Cholet pour son aide précieuse.

Communiqué de presse Mathis Gasser :

Mathis Gasser est né en 1984 (CH), il vit et travaille à Londres.

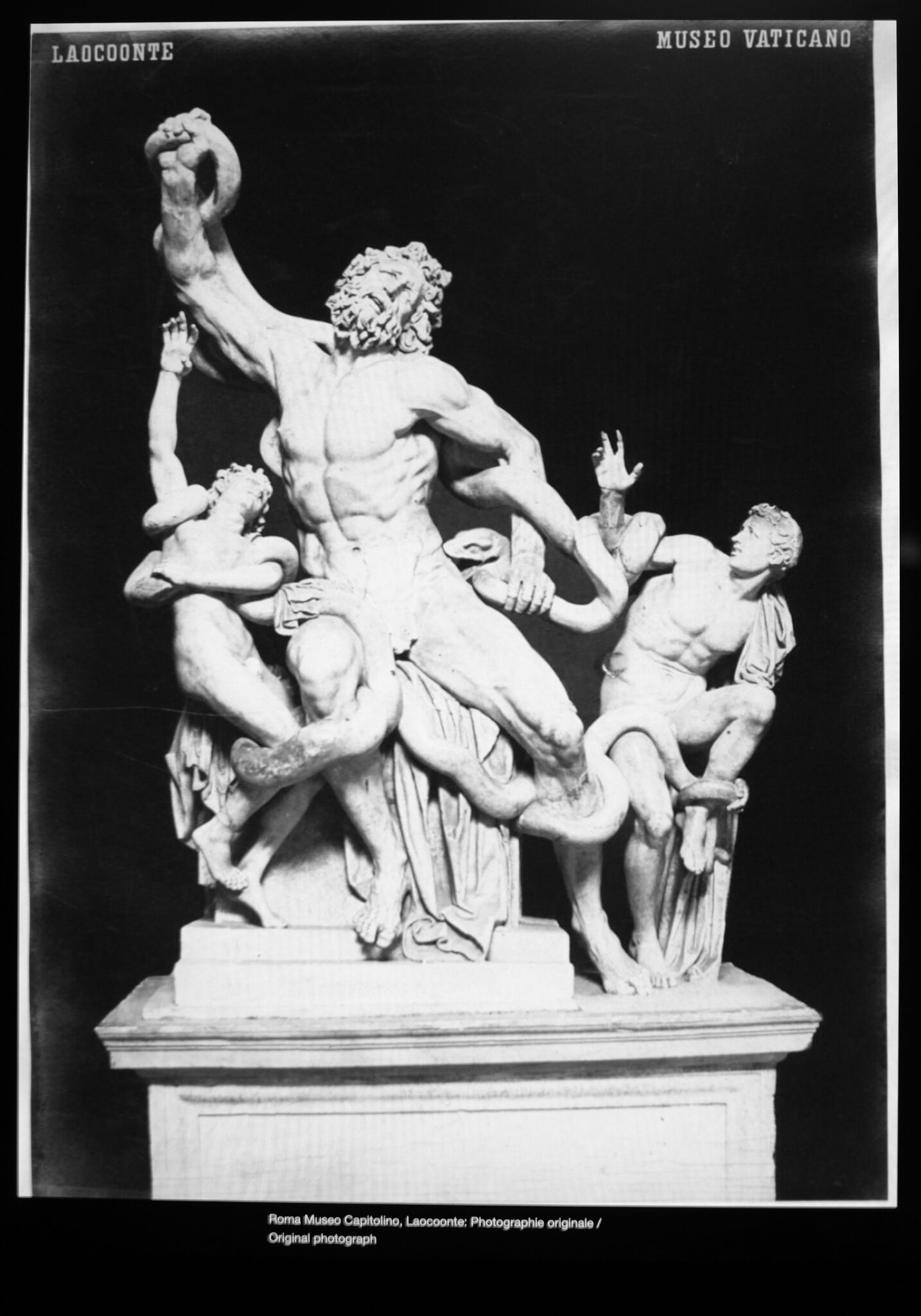

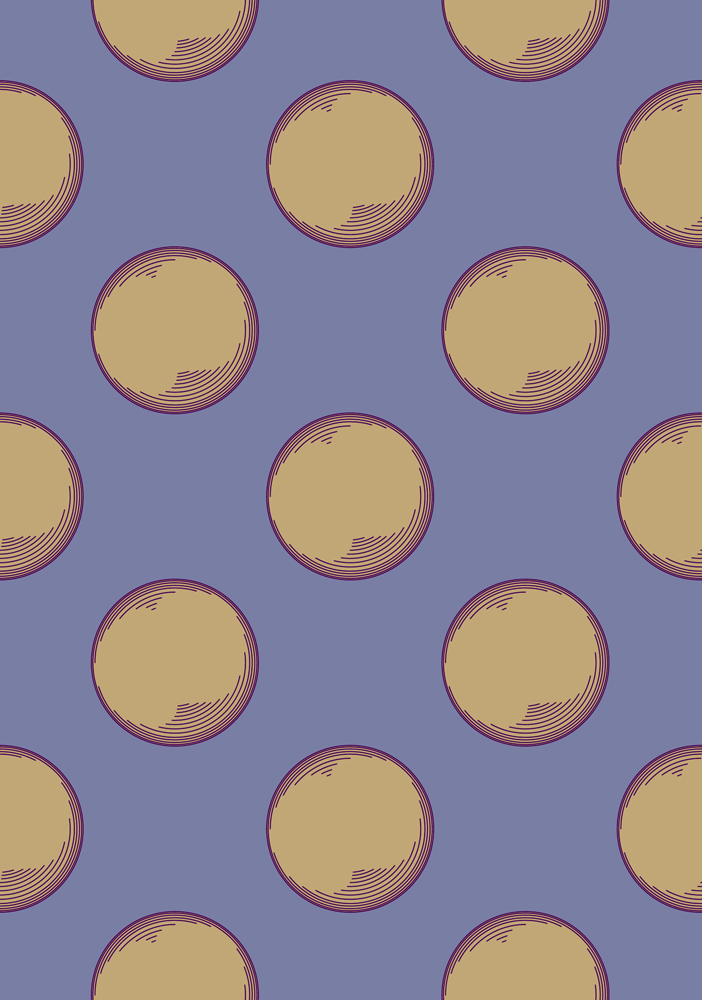

L’exposition de la Salle de bains est l’occasion de montrer pour la première fois une série de peintures, de courtes vidéos et un poster comprenant toutes les images et les documents à partir desquels il travaille. Il construit en effet le plus souvent ses pièces à partir d’images appropriées. Il peint d’après des couvertures de livres, des détails de peintures célèbres, des images tirées de films ou de shows tv, des posters ou des publicités, et il puise très largement dans l’histoire de l’art et de la culture visuelle. Son travail se caractérise donc par une impressionnante densité de citations, ainsi que par une large gamme de gestes d’appropriation différents. Le geste de peinture devient alors un moyen d’appréhender, comprendre et transmettre chaque image.

Mais chaque peinture de Gasser, bien que pouvant être regardée de manière autonome, peut aussi être resituée dans un discours plus large, et mise en rapport avec toutes les autres : il explore ainsi son potentiel, c’est-à-dire sa capacité à intégrer un discours qui la surplombe, une opération qui peut s’accomplir diversement. Une des possibilités de cette intégration consiste en l’écriture d’un script, ce que Gasser a fait avec In the Museum 1 et 2 (2011-2013), vidéo dans laquelle Christopher Walken (ou plutôt sa marionnette) déambule dans une exposition, dans un espace qui rappelle les grands musées américains (selon le principe de l’exposition comme film). L’organisation de ses peintures dans un projet qui les subsume en est une autre et c’est ainsi que fonctionne The Alien Project.

Entamé en 2012, The Alien Project est un projet protéiforme qui est appelé à se déployer à travers de nombreuses expositions et dans différents médiums (peintures, vidéo, installation in situ...). Ce projet s’intéresse à l’impact que la découverte potentielle d’êtres extraterrestres pourrait avoir sur les structures gouvernementales. Dans les fictions, les créatures aliens sont souvent dépeintes comme maléfiques et mal intentionnées, ce qui est déplorable (mais vient souvent nourrir la structure dramatique des récits). Pour The Alien Project, l’alien sort du contexte cinématographique pour devenir une créature de pensée, permettant d’élaborer de nouvelles manières d’envisager ce que serait l’Autre. Il est en effet probable que devant une forme de vie extraterrestre, nous serions tentés d’avoir recours à des réflexes anthropomorphiques. Il est également probable que l’arrivée des extra-terrestres sur Terre agirait comme un séisme puissant venant déplacer d’un coup, et violemment, les fondements à partir des quels les peuples humains envisagent leur identité.

Ainsi The Alien Project s’appuie sur différentes questions, communes au champ de la science-fiction : comment l’humanité réagirait-elle si les aliens essayaient d’entrer en contact ? Est-il possible d’appréhender le non-humain d’une manière appropriée ? Pour Mathis Gasser, l’alien est un concept : il représente à la fois le futur et la nouveauté, une étrangeté maximale, pour reprendre un concept très souvent utilisé par l’artiste (un emprunt au « maximal Fremde » de M. Schetsche, alien signifie d’ailleurs étymologiquement « autre »). « Je veux travailler avec des images qui -pour moi- pointent dans une direction qui est celle du «vocabulaire du futur» » explique encore Gasser. Ainsi la figure de l’alien est-elle pour lui une manière de s’interroger sur diverses formes de construction du futur à la fois politique, biologique et esthétique.

Elle lui permet notamment d’imaginer ce que pourrait être un transnationalisme, l’élaboration d’un bien public par-delà les frontières nationales, un travail d’imagination qui prend par exemple dans ses peintures la forme d’une interrogation sur les superstructures.

Dans cette perspective l’imagerie universaliste qui a nourri à la fois le charity business dans les années 1980, la publicité (avec Benetton comme meilleur exemple), ou la communication corporate vantant les mérites d’une globalisation intense, ne sont pas convoquées par l’artiste, car elles reposent toutes sur des visions privatisées, impérialistes ou commerciales de ce que serait une appartenance non plus nationale, mais mondiale.

En revanche, Mathis Gasser mentionne l’Europe, en tant que construction politique, économique et territoriale, comme étant une forme de modèle possible, une première ébauche de ce transnationalisme. Il évoque également le CERN, ou la Station Spatiale Internationale, des projets tellement lourds en termes financiers et technologiques qu’ils requièrent des formes de collaboration qui dépassent les frontières. Les biennales seraient un autre modèle possible, si elles ne se contentaient pas de transposer souvent littéralement les inégalités dans le champ de l’art, ou de marchandiser les appartenances nationales.

En 1966, Stewart Brand, auteur et activiste américain, a pris contact avec la NASA pour que soit prise et diffusée une photographie de la Terre vue depuis l’espace, conscient du symbole extrêmement fort que pourrait posséder cette image. Renouant avec cette tradition utopique, Mathis Gasser essaie aujourd’hui d’imaginer, et de peindre des symboles de ce type pour essayer de repenser l’avenir.

Space Soap Strange Hypnosis Opera is the title shared by the two solo shows currently on view at La Salle des Bains, David Evrard’s and Mathis Gasser’s (whose first solo exhibition in France this is).

Press release David Evrard :

It is unfortunately not possible to fit the entire world into a press release. But because it is nevertheless important to provide some precise information and one or two reading clues to visitors who have come to discover his exhibition, let us start by saying that David Evrard is a Belgian artist and author who, after growing up in Liège, settled in Brussels; that he is the king of mixed techniques (sculpture, photography, collage, writing, painting); and that we find this outburst of activity in the exhibition (a framed poster of the Stray Cats, large wall posters depicting general images of tropical paradises, water colours of pizzas, a large tapestry, sculptures, a print on canvas). The source of these objects does not much matter: some are retrieved and slightly altered, others are used like readymades, others still are the result of commissions, and others, last of all, are made by the artist. The association of all these things is marked by a very strong link with improvisation, a process which became central for the artist after a brief course with John Cage at the Liège Conservatory in the very early 1990s. So what matters is not so much what each object per se might have to say about a certain know-how, a technique peculiar to artists, as their respective capacity to make their origin and their method of production visible, and deliberately create a form of disorder. In David Evrard’s work, generosity rules. Generosity of accumulated images and forms (the hamburger and the pizza are two of the practical models, he explains, for sculptures in layers, models that we find in the exhibition). Generosity of references, and of good stories, too (if you secretly love a successful American artist, a French heritage curator who curated a recent Documenta, the son of a famous painter of the 1980s who became a film-maker, a Russian-born Belgian winner of the Novel chemistry prize, or a bass guitarist, guitarist and singer in the world’s most famous indie rock group, reckon that David Evrard has already spent an evening with her, or him). “I really like culture in general”, he explains. “This is why I’m interested in all these things, country folk as much as small anarchist groups, and comics, and Faulker, Flaubert and Mallarmé. The last book I just finished was Assassin Creeds, written based on a video game, and as I read it I really asked myself about ekphrasis...” Through these mixtures of references, materials and sources, he does not try and put all cultural objects at the same level. What interests him is making his own way through culture, and describing his perforce amorous relations—always full of enthusiasm—with his products.

The exhibition thus points in the direction of fan art with the tapestry Die Antwoord (a South African zef hip hop group) and the portrait of the Stray Cats, who identified themselves so much with the position of the fan that they reproduced a musical world more than twenty years old in their music and in their look. They got together in the late 1970s in New York state, and quickly went into exile in London, where they were successful, with their precise rockabilly style (they had the same guitar as Eddie Cochran, an orange Gretsch 6120). The Stray Cats are, in a way, the exhibition’s mascot, they are “at once incredibly fuddy-duddy and incredibly wonderful”, they incarnate, the artist explains, an “epic fuddy-duddiness”. The stance of the fan (be it in music, pop mythology, contemporary art, zombie movies, psychobilly, kitsch, and all the possible cultural constellations...), understood as a productive way of digesting capitalism and its products, might thus be a good model for understanding the accumulations made by the artist.

His work is also informed by a way of thinking about retrieval and recycling. And it is in this process—relying on precarious and outcast things to put them back into circulation and offer them legitimacy—that the political content of his work resides. The artist incidentally relates this precariousness to his own story: he grew up in the suburbs of Liège, and belongs to a generation for whom the suburbs, he says, have become a genre in its own right, something marginal and down-graded, which is now laying claim to itself. He is the same age, he reminds us, as Joey Starr and Tricky, with whom he did an interview, published in 2011 in the first issue of the magazine YEAR (published by Komplot, a not-for-profit Brussels space created and run by Sonia Dermience, which David Evrard is an active member of).

His work happily broaches these issues without any didacticism, meaning in the forms themselves (they bear the traces of their manufacture, their circulation, and their elevation), and in a form of assumed wit. After all, David Evrard is the kind of artist who puts pizzas in palm trees.

Translated by Simon Pleasance & Fronza Woods

David Evrard is gateful to Nadine Cholet for her valuable help.

Press release Mathis Gasser :

Mathis Gasser was born in 1984 in Switzerland; he lives and works in London.

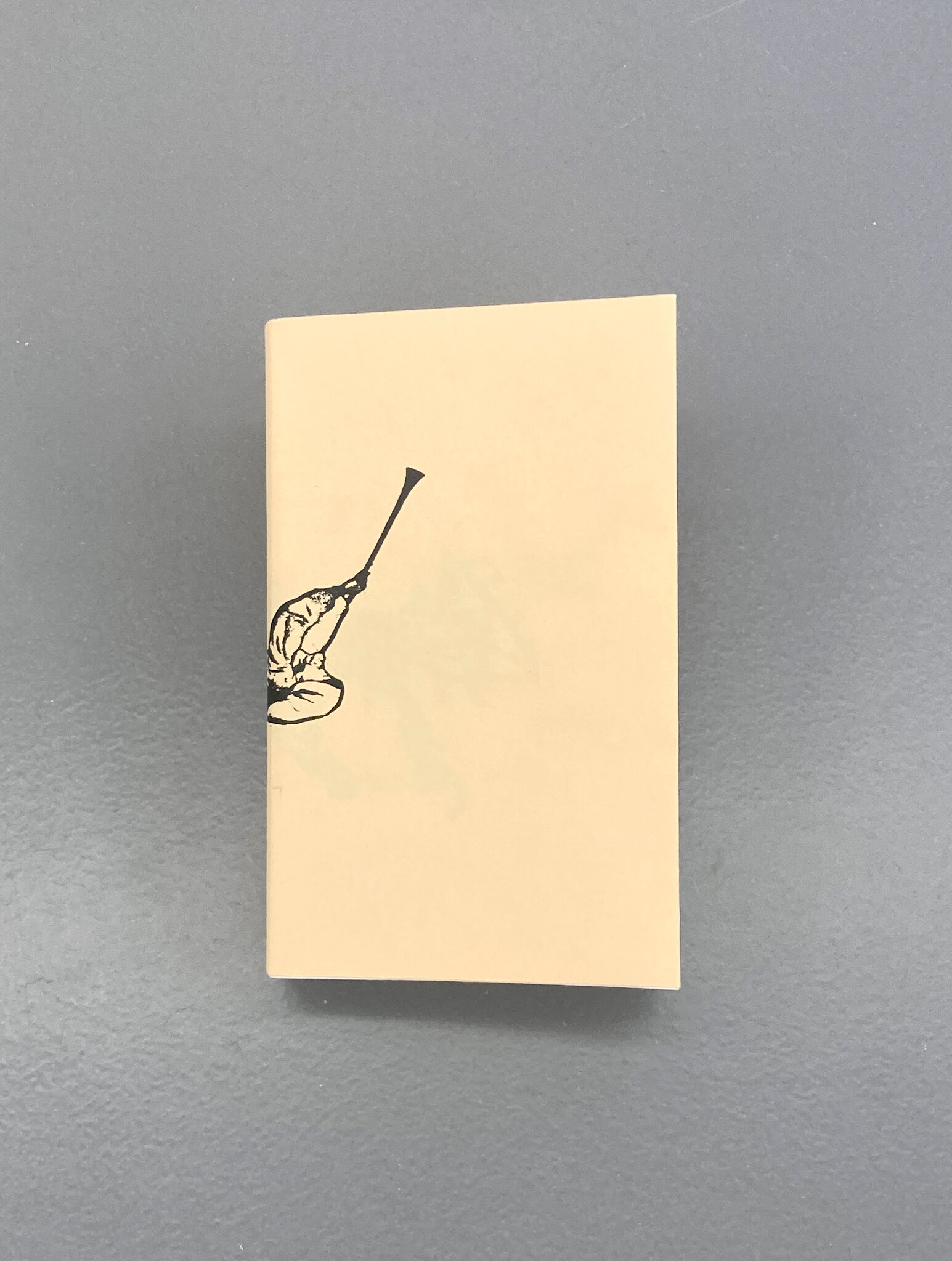

The exhibition at La Salle de Bains offers an opportunity to show, for the first time, a series of paintings, short videos and a poster containing all the images and documents from which he works. He actually usually constructs his pieces from appropriated images. He paints from book covers, details of famous paintings, images taken from films and TV shows, posters and advertisements, and he draws a great deal from art history and the history of visual culture. So his work is hallmarked by an impressive density of references, as well as by a broad range of different gestures of appropriation. The gesture of painting therefore becomes a way of grasping, understanding and transmitting each image.

But although each one of Gasser’s paintings can be looked at in an autonomous way, they can also be resituated in a wider discourse, and linked with all the others: he thus explores his potential, meaning his capacity to incorporate a discourse which surveys his work, an operation which can be achieved in diverse ways. One of the possibilities of this integration consists in the writing of a script, which Gasser did with In the Museum 1 and 2 (2011-2013), a video in which Christopher Walken (or rather his puppet) strolls around an exhibition, in a space that calls to mind major American museums (based on the principle of the exhibition as film). The organization of his paintings in a project that subsumes them is another possibility, and this is how The Alien Project works.

Embarked upon in 2012, The Alien Project is a multi-facetted work that develops and unfolds through numerous shows and in different media (paintings, video, in situ installation...). This project is concerned with the impact which the potential discovery of extra-terrestrial beings might have on government organizations. In fictional works, alien creatures are often depicted as malevolent and ill-intentioned, which is regrettable (but often fuels the dramatic structure of these tales). For The Alien Project, the alien escapes from the film context and becomes a thinking creature, making it possible to work out new ways of imagining what the Other might be. It is in fact quite likely that in front of a form of extra-terrestrial life, we would be tempted to have recourse to anthropomorphic reflexes. It is also probably that the arrival of extra-terrestrials on Planet Earth would act like a powerful earthquake, suddenly and violently shifting the foundations on which human beings imagine their identity.

So The Alien Project is based on different issues, shared by the field of science-fiction: how would human-kind react if aliens tried to get in contact with us? Is it possible to understand the non-human in an appropriate way? For Mathis Gasser, the alien is a concept: it represents both the future and novelty, something of maximum strangeness, to borrow a concept very frequently used by the artist (a borrowing from M. Schetsche’s “maximal Fremde”—alien incidentally means “other” etymologically). “I want to work with images which—for me—point in a direction which is that of the “vocabulary of the future”, Gasser explains further. So the figure of the alien is, for him, a way of raising questions about various forms of construction of the future, at once political, biological and aesthetic. In particular, it enables him to imagine what trans-nationalism might be, the development of a public good beyond national borders, a work of imagination which, in his paintings, takes on, for example, the form of a questioning about superstructures.In this perspective, the universalist imagery that has informed both the charity business in the 1980s, advertising (with Benetton as the best example), and corporate communications boasting about the merits of an intense globalization, are not summoned up by the artist, because they are all based on privatized, inperialist and commercial visions of what a membership would be that is no longer national, but international.

On the other hand, Mathis Gasser refers to Europe, as a political, economic and territorial construct, as being a possible form of model, a first draft of transnationalism. He also refers to the CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, and the International Space Station, projects which are so top-heavy in financial and technological terms that they call for forms of cooperation that go beyond frontiers. Biennial events might be another possible model, if they were not limited to often literally transposing inequalities in the art fields, and commercializing national memberships.In 1966, Stewart Brand, an American author and activist, got in touch with NASA so that a photograph of the Earth seen from space could be taken and broadcast, aware, as he was, of the extremely powerful symbol that such an image might have. In linking back up with that utopian tradition, Mathis Gasser is today trying to imagine and paint symbols of this type in order to try and rethink the future.

Translated by Simon Pleasance & Fronza Woods

Press release David Evrard :

It is unfortunately not possible to fit the entire world into a press release. But because it is nevertheless important to provide some precise information and one or two reading clues to visitors who have come to discover his exhibition, let us start by saying that David Evrard is a Belgian artist and author who, after growing up in Liège, settled in Brussels; that he is the king of mixed techniques (sculpture, photography, collage, writing, painting); and that we find this outburst of activity in the exhibition (a framed poster of the Stray Cats, large wall posters depicting general images of tropical paradises, water colours of pizzas, a large tapestry, sculptures, a print on canvas). The source of these objects does not much matter: some are retrieved and slightly altered, others are used like readymades, others still are the result of commissions, and others, last of all, are made by the artist. The association of all these things is marked by a very strong link with improvisation, a process which became central for the artist after a brief course with John Cage at the Liège Conservatory in the very early 1990s. So what matters is not so much what each object per se might have to say about a certain know-how, a technique peculiar to artists, as their respective capacity to make their origin and their method of production visible, and deliberately create a form of disorder. In David Evrard’s work, generosity rules. Generosity of accumulated images and forms (the hamburger and the pizza are two of the practical models, he explains, for sculptures in layers, models that we find in the exhibition). Generosity of references, and of good stories, too (if you secretly love a successful American artist, a French heritage curator who curated a recent Documenta, the son of a famous painter of the 1980s who became a film-maker, a Russian-born Belgian winner of the Novel chemistry prize, or a bass guitarist, guitarist and singer in the world’s most famous indie rock group, reckon that David Evrard has already spent an evening with her, or him). “I really like culture in general”, he explains. “This is why I’m interested in all these things, country folk as much as small anarchist groups, and comics, and Faulker, Flaubert and Mallarmé. The last book I just finished was Assassin Creeds, written based on a video game, and as I read it I really asked myself about ekphrasis...” Through these mixtures of references, materials and sources, he does not try and put all cultural objects at the same level. What interests him is making his own way through culture, and describing his perforce amorous relations—always full of enthusiasm—with his products.

The exhibition thus points in the direction of fan art with the tapestry Die Antwoord (a South African zef hip hop group) and the portrait of the Stray Cats, who identified themselves so much with the position of the fan that they reproduced a musical world more than twenty years old in their music and in their look. They got together in the late 1970s in New York state, and quickly went into exile in London, where they were successful, with their precise rockabilly style (they had the same guitar as Eddie Cochran, an orange Gretsch 6120). The Stray Cats are, in a way, the exhibition’s mascot, they are “at once incredibly fuddy-duddy and incredibly wonderful”, they incarnate, the artist explains, an “epic fuddy-duddiness”. The stance of the fan (be it in music, pop mythology, contemporary art, zombie movies, psychobilly, kitsch, and all the possible cultural constellations...), understood as a productive way of digesting capitalism and its products, might thus be a good model for understanding the accumulations made by the artist.

His work is also informed by a way of thinking about retrieval and recycling. And it is in this process—relying on precarious and outcast things to put them back into circulation and offer them legitimacy—that the political content of his work resides. The artist incidentally relates this precariousness to his own story: he grew up in the suburbs of Liège, and belongs to a generation for whom the suburbs, he says, have become a genre in its own right, something marginal and down-graded, which is now laying claim to itself. He is the same age, he reminds us, as Joey Starr and Tricky, with whom he did an interview, published in 2011 in the first issue of the magazine YEAR (published by Komplot, a not-for-profit Brussels space created and run by Sonia Dermience, which David Evrard is an active member of).

His work happily broaches these issues without any didacticism, meaning in the forms themselves (they bear the traces of their manufacture, their circulation, and their elevation), and in a form of assumed wit. After all, David Evrard is the kind of artist who puts pizzas in palm trees.

Translated by Simon Pleasance & Fronza Woods

David Evrard is gateful to Nadine Cholet for her valuable help.

Press release Mathis Gasser :

Mathis Gasser was born in 1984 in Switzerland; he lives and works in London.

The exhibition at La Salle de Bains offers an opportunity to show, for the first time, a series of paintings, short videos and a poster containing all the images and documents from which he works. He actually usually constructs his pieces from appropriated images. He paints from book covers, details of famous paintings, images taken from films and TV shows, posters and advertisements, and he draws a great deal from art history and the history of visual culture. So his work is hallmarked by an impressive density of references, as well as by a broad range of different gestures of appropriation. The gesture of painting therefore becomes a way of grasping, understanding and transmitting each image.

But although each one of Gasser’s paintings can be looked at in an autonomous way, they can also be resituated in a wider discourse, and linked with all the others: he thus explores his potential, meaning his capacity to incorporate a discourse which surveys his work, an operation which can be achieved in diverse ways. One of the possibilities of this integration consists in the writing of a script, which Gasser did with In the Museum 1 and 2 (2011-2013), a video in which Christopher Walken (or rather his puppet) strolls around an exhibition, in a space that calls to mind major American museums (based on the principle of the exhibition as film). The organization of his paintings in a project that subsumes them is another possibility, and this is how The Alien Project works.

Embarked upon in 2012, The Alien Project is a multi-facetted work that develops and unfolds through numerous shows and in different media (paintings, video, in situ installation...). This project is concerned with the impact which the potential discovery of extra-terrestrial beings might have on government organizations. In fictional works, alien creatures are often depicted as malevolent and ill-intentioned, which is regrettable (but often fuels the dramatic structure of these tales). For The Alien Project, the alien escapes from the film context and becomes a thinking creature, making it possible to work out new ways of imagining what the Other might be. It is in fact quite likely that in front of a form of extra-terrestrial life, we would be tempted to have recourse to anthropomorphic reflexes. It is also probably that the arrival of extra-terrestrials on Planet Earth would act like a powerful earthquake, suddenly and violently shifting the foundations on which human beings imagine their identity.

So The Alien Project is based on different issues, shared by the field of science-fiction: how would human-kind react if aliens tried to get in contact with us? Is it possible to understand the non-human in an appropriate way? For Mathis Gasser, the alien is a concept: it represents both the future and novelty, something of maximum strangeness, to borrow a concept very frequently used by the artist (a borrowing from M. Schetsche’s “maximal Fremde”—alien incidentally means “other” etymologically). “I want to work with images which—for me—point in a direction which is that of the “vocabulary of the future”, Gasser explains further. So the figure of the alien is, for him, a way of raising questions about various forms of construction of the future, at once political, biological and aesthetic. In particular, it enables him to imagine what trans-nationalism might be, the development of a public good beyond national borders, a work of imagination which, in his paintings, takes on, for example, the form of a questioning about superstructures.In this perspective, the universalist imagery that has informed both the charity business in the 1980s, advertising (with Benetton as the best example), and corporate communications boasting about the merits of an intense globalization, are not summoned up by the artist, because they are all based on privatized, inperialist and commercial visions of what a membership would be that is no longer national, but international.

On the other hand, Mathis Gasser refers to Europe, as a political, economic and territorial construct, as being a possible form of model, a first draft of transnationalism. He also refers to the CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, and the International Space Station, projects which are so top-heavy in financial and technological terms that they call for forms of cooperation that go beyond frontiers. Biennial events might be another possible model, if they were not limited to often literally transposing inequalities in the art fields, and commercializing national memberships.In 1966, Stewart Brand, an American author and activist, got in touch with NASA so that a photograph of the Earth seen from space could be taken and broadcast, aware, as he was, of the extremely powerful symbol that such an image might have. In linking back up with that utopian tradition, Mathis Gasser is today trying to imagine and paint symbols of this type in order to try and rethink the future.

Translated by Simon Pleasance & Fronza Woods

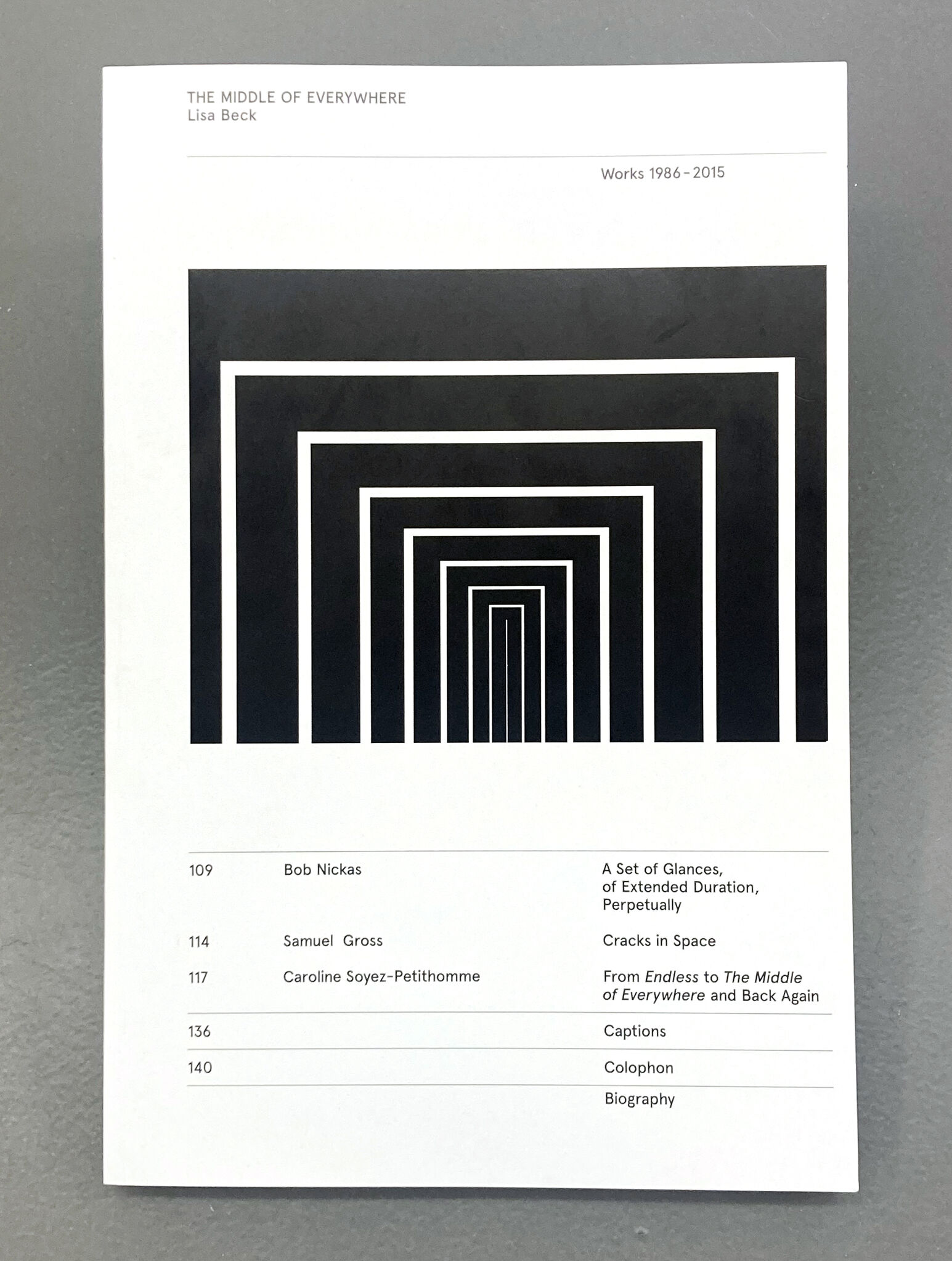

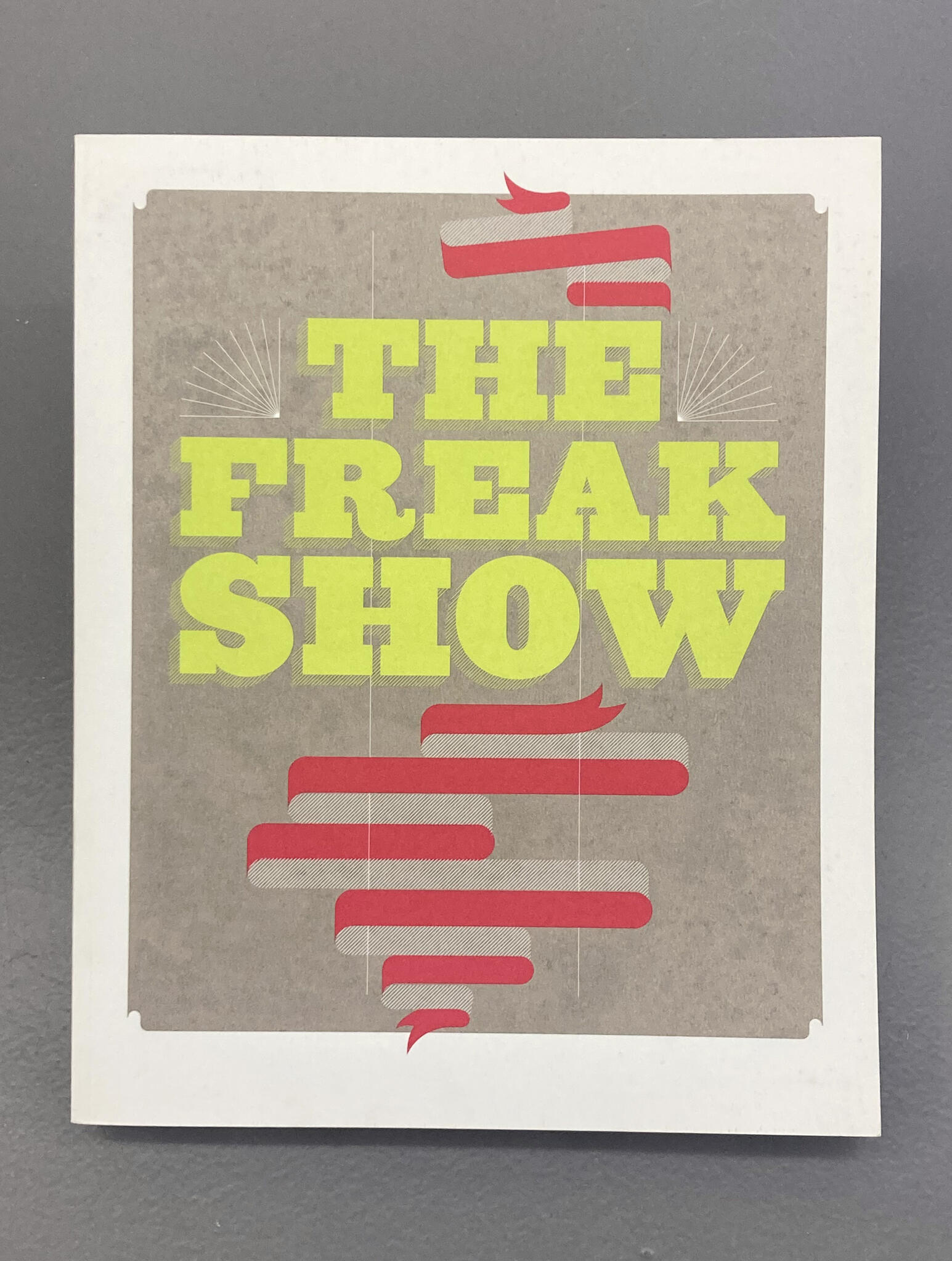

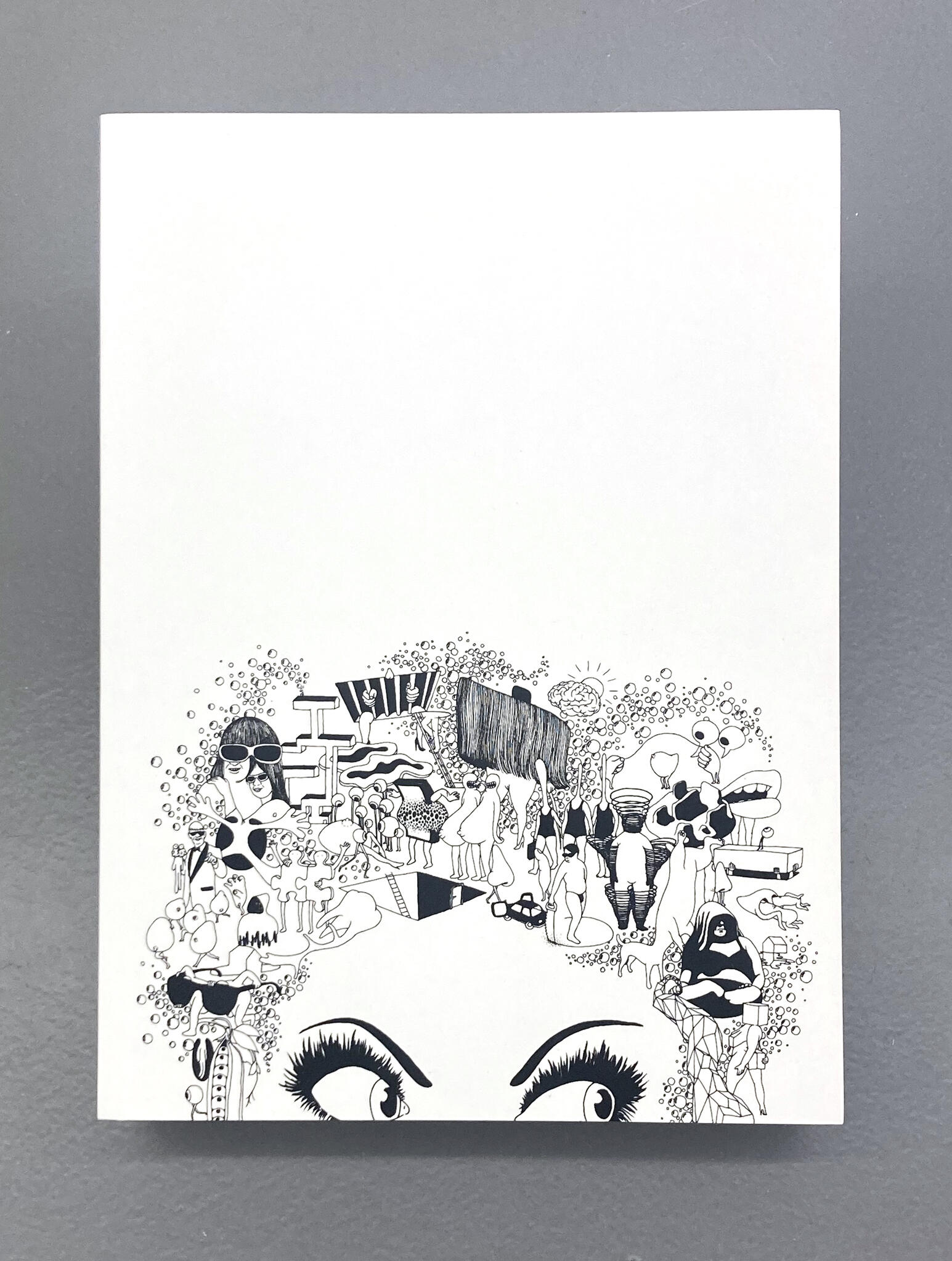

Space Soap Strange Hypnosis Opera, 2013

carton d'invitation

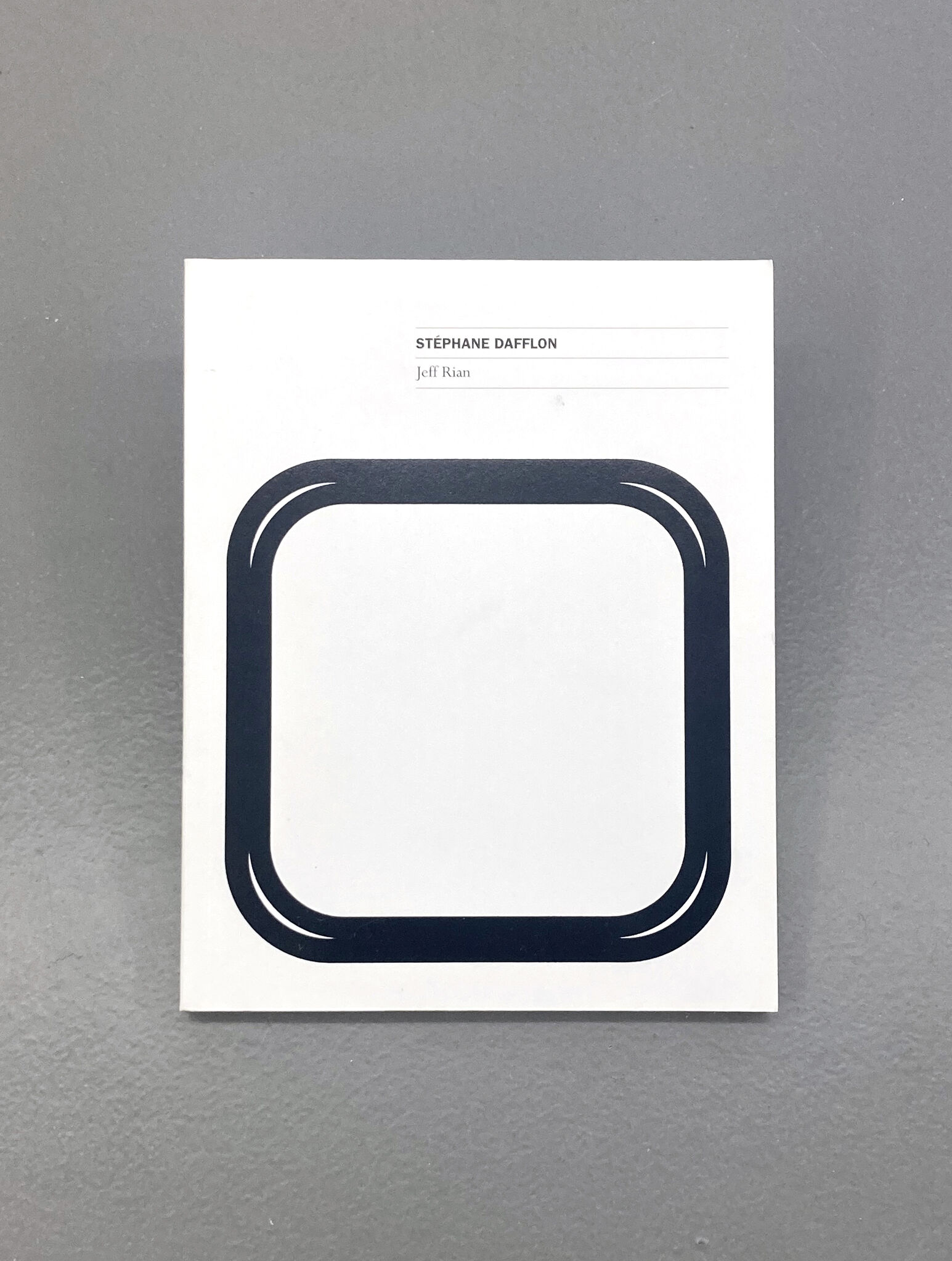

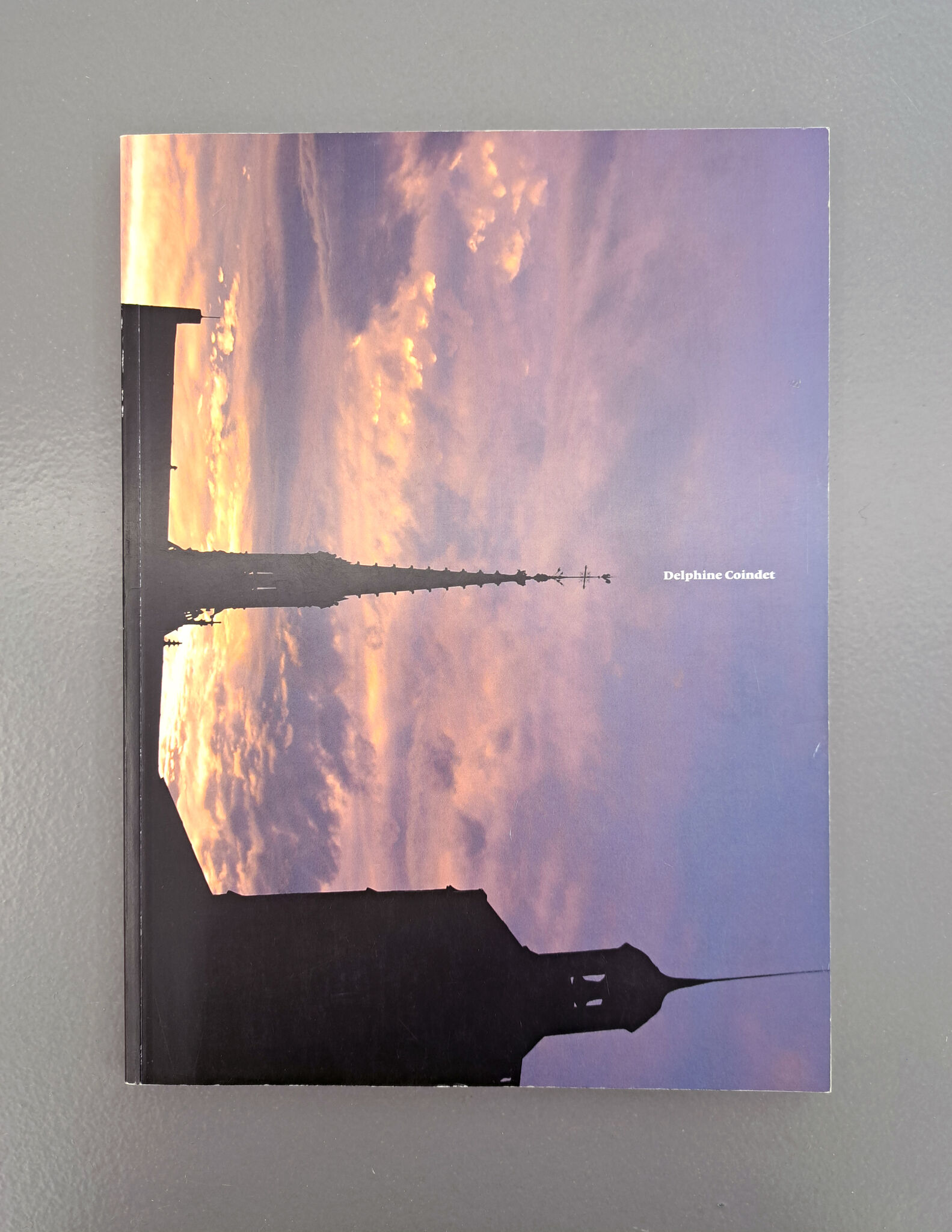

Mathis Gasser, né en 1984 (Suisse).

Vit et travaille à Londres.

Représenté par Ribordy Contemporary.

Vit et travaille à Londres.

Représenté par Ribordy Contemporary.

Mathis Gasser, né en 1984 (Suisse).

Vit et travaille à Londres.

Représenté par Ribordy Contemporary.

Vit et travaille à Londres.

Représenté par Ribordy Contemporary.

La Salle de bains reçoit le soutien du Ministère de la Culture DRAC Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes,

de la Région Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes et de la Ville de Lyon.

Cette exposition reçoit le soutien de Pro Helvetia - Fondation suisse pour la culture,

et de WBI - Wallonie-Bruxelles International.

de la Région Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes et de la Ville de Lyon.

Cette exposition reçoit le soutien de Pro Helvetia - Fondation suisse pour la culture,

et de WBI - Wallonie-Bruxelles International.