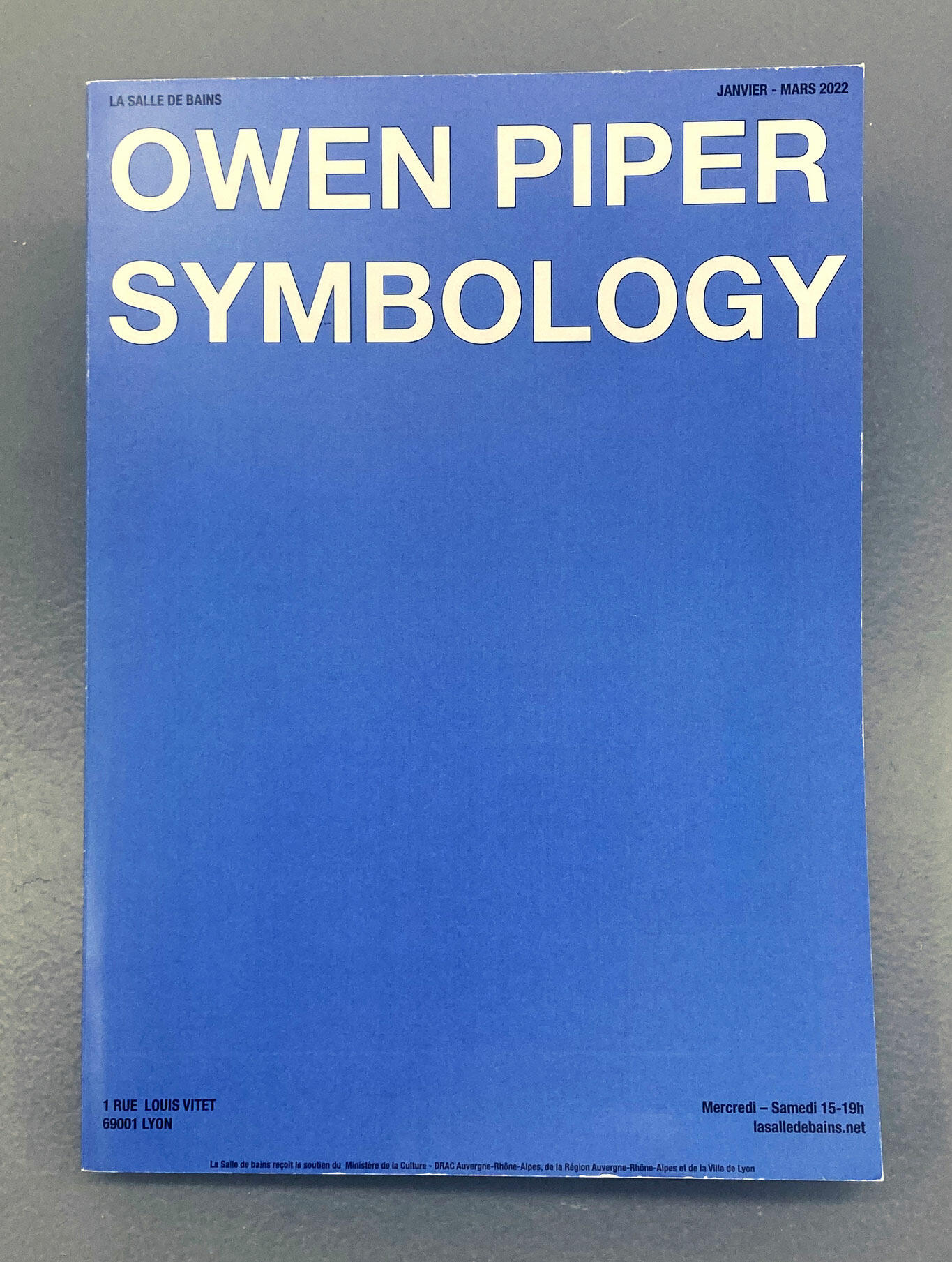

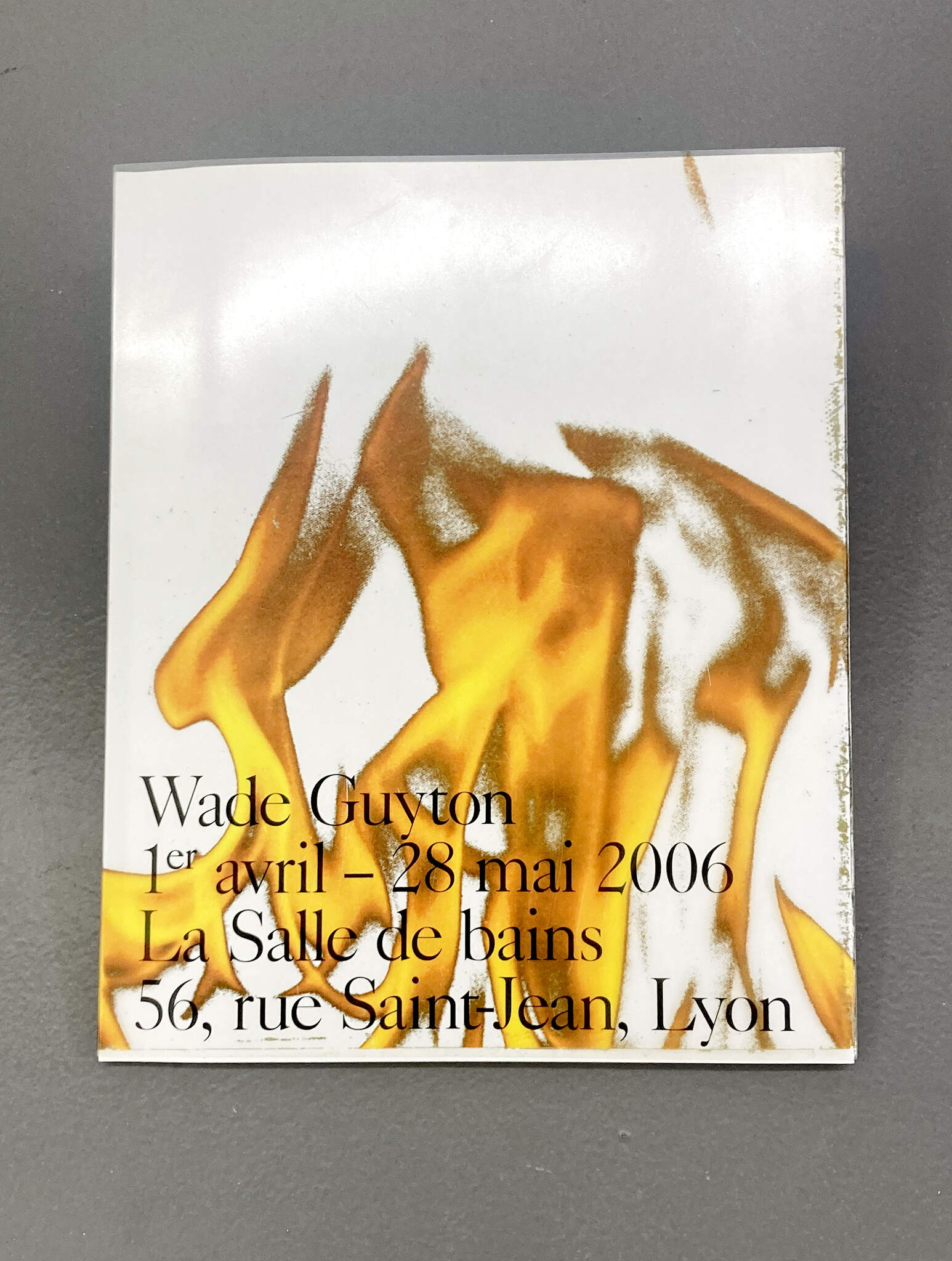

Babes, Fiona Mackay, la Salle de bains, Lyon. Du 10 septembre au 9 octobre 2021.

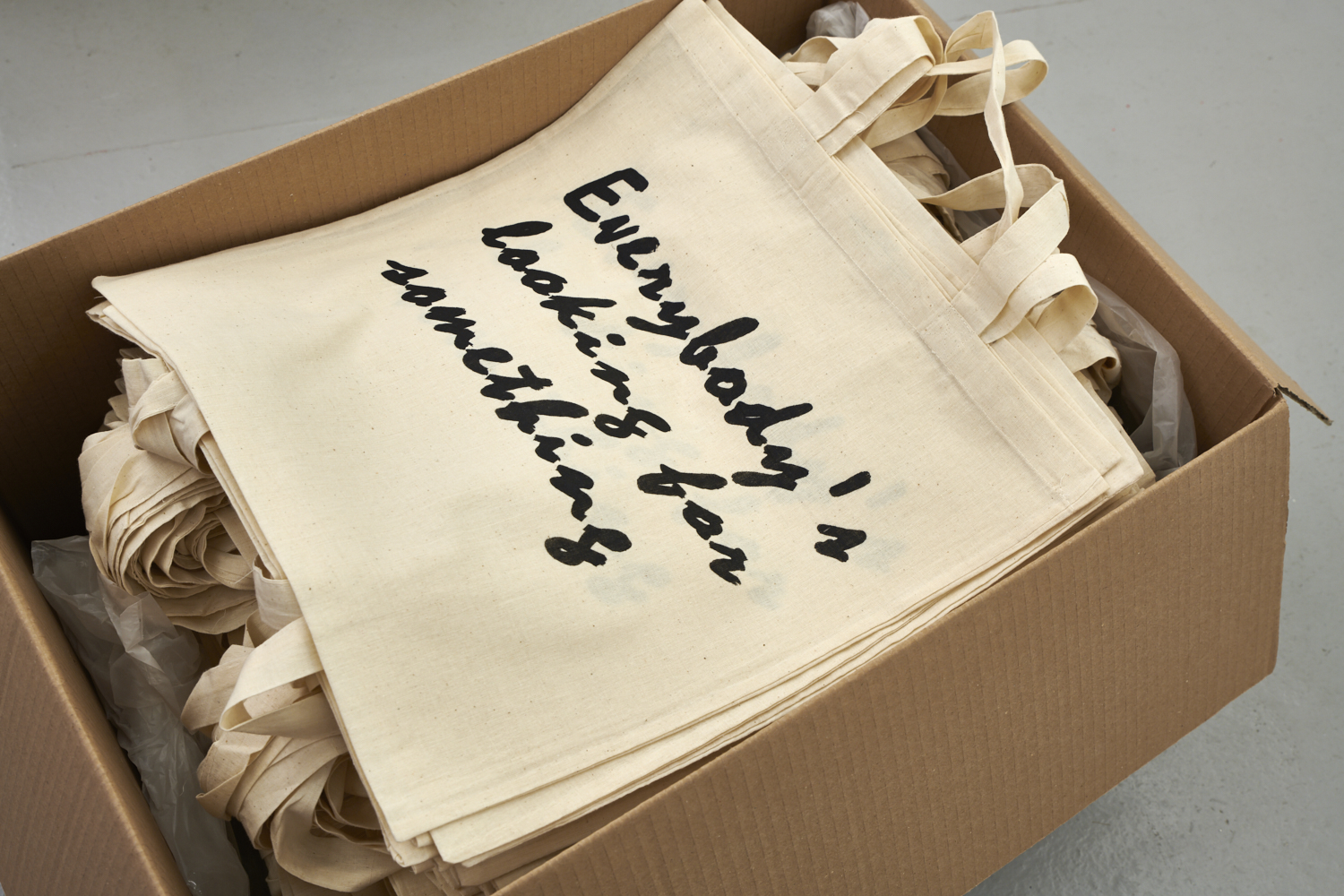

Photo: Jesús Alberto Benítez

Photo: Jesús Alberto Benítez

Babes, Fiona Mackay, la Salle de bains, Lyon. From 10 Septembre to 9 October 2021.

Photo: Jesús Alberto Benítez

Photo: Jesús Alberto Benítez

Babes

Du 10 septembre au 9 octobre 2021From 10 September to 9 October 2021

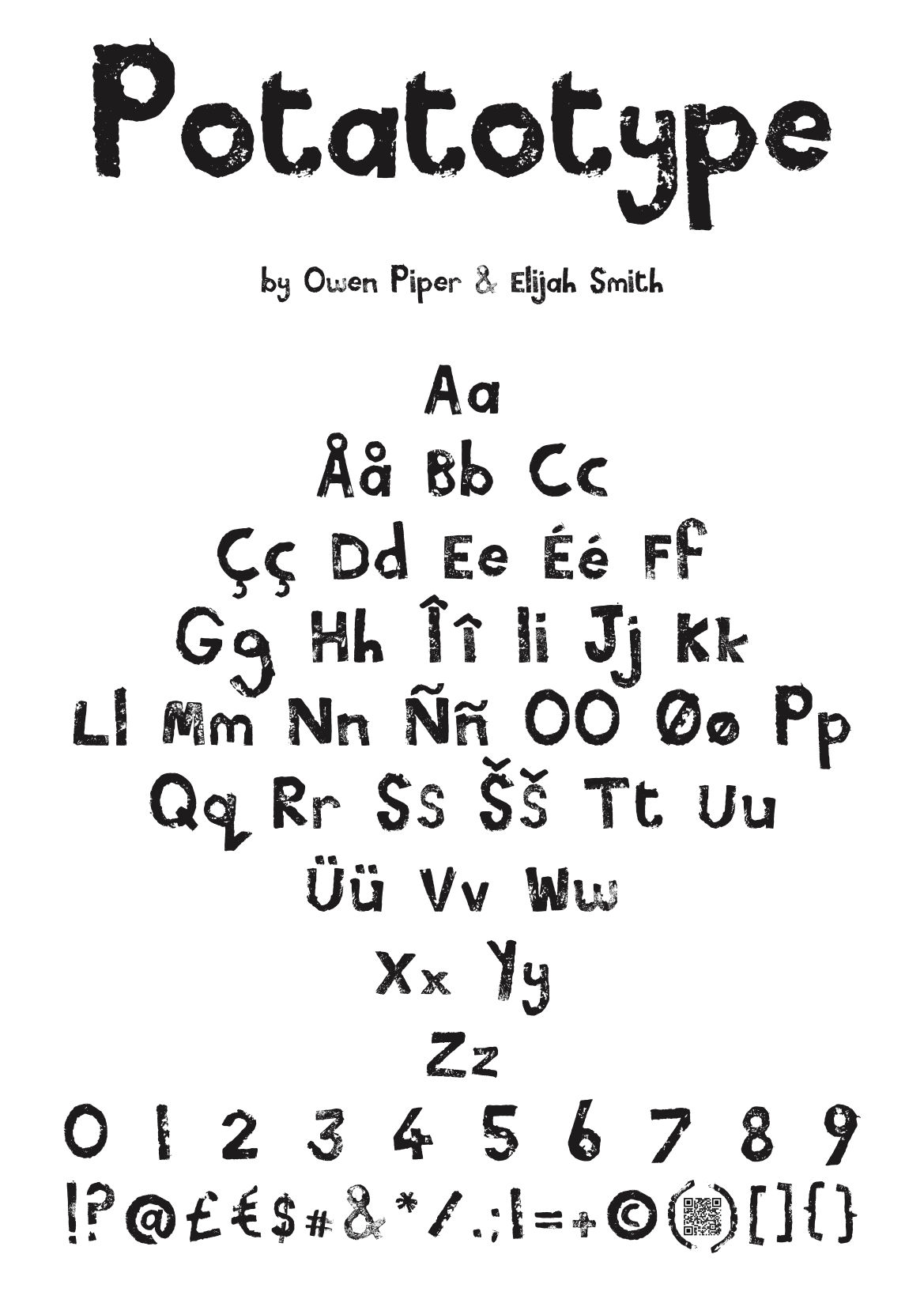

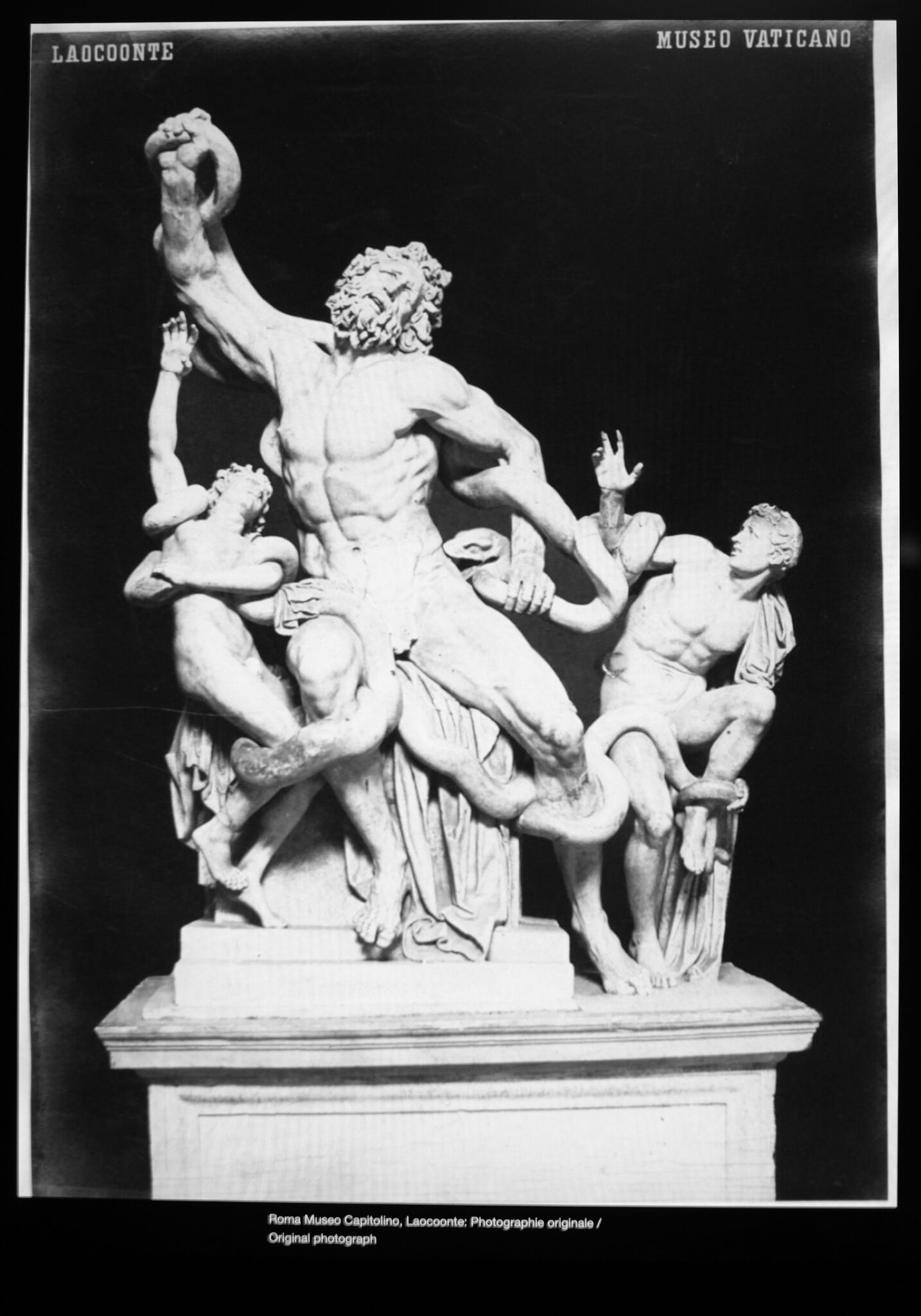

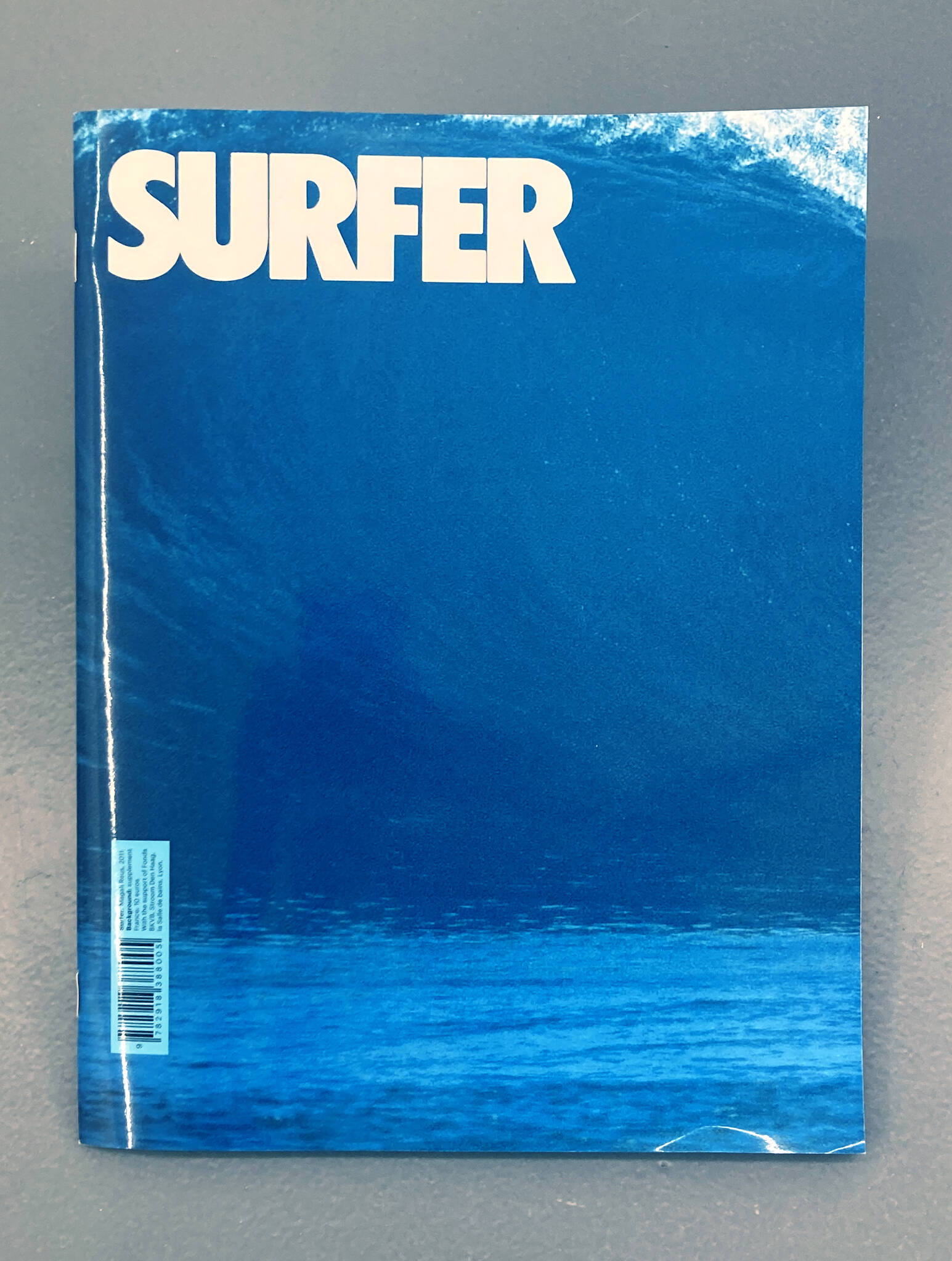

Le texte qui introduisait le chapitre précédent évoquait l’image de l’artiste dans la solitude de son atelier, accaparée par un été de travail intense. Pendant ce temps, dans les rues de la ville somnolente, apparaissaient de manière sporadique des affiches sans message distillant chaque semaine, tel un récit discontinu mais aussi une opération de communication nonchalante, des visions légèrement érotiques. Selon le jour et l’heure, l’on aurait pu surprendre ces silhouettes d’Apollon et de Narcisse (et parfois ensemble) encore humides, fraichement étalées sur leur panneau, ou bien gondolées sous l’effet de la chaleur et du temps. Quelquefois, on les trouvait partiellement recouvertes d’autres annonces que ces éphèbes arboraient avec mépris, comme une irrévérence à leur beauté classique.

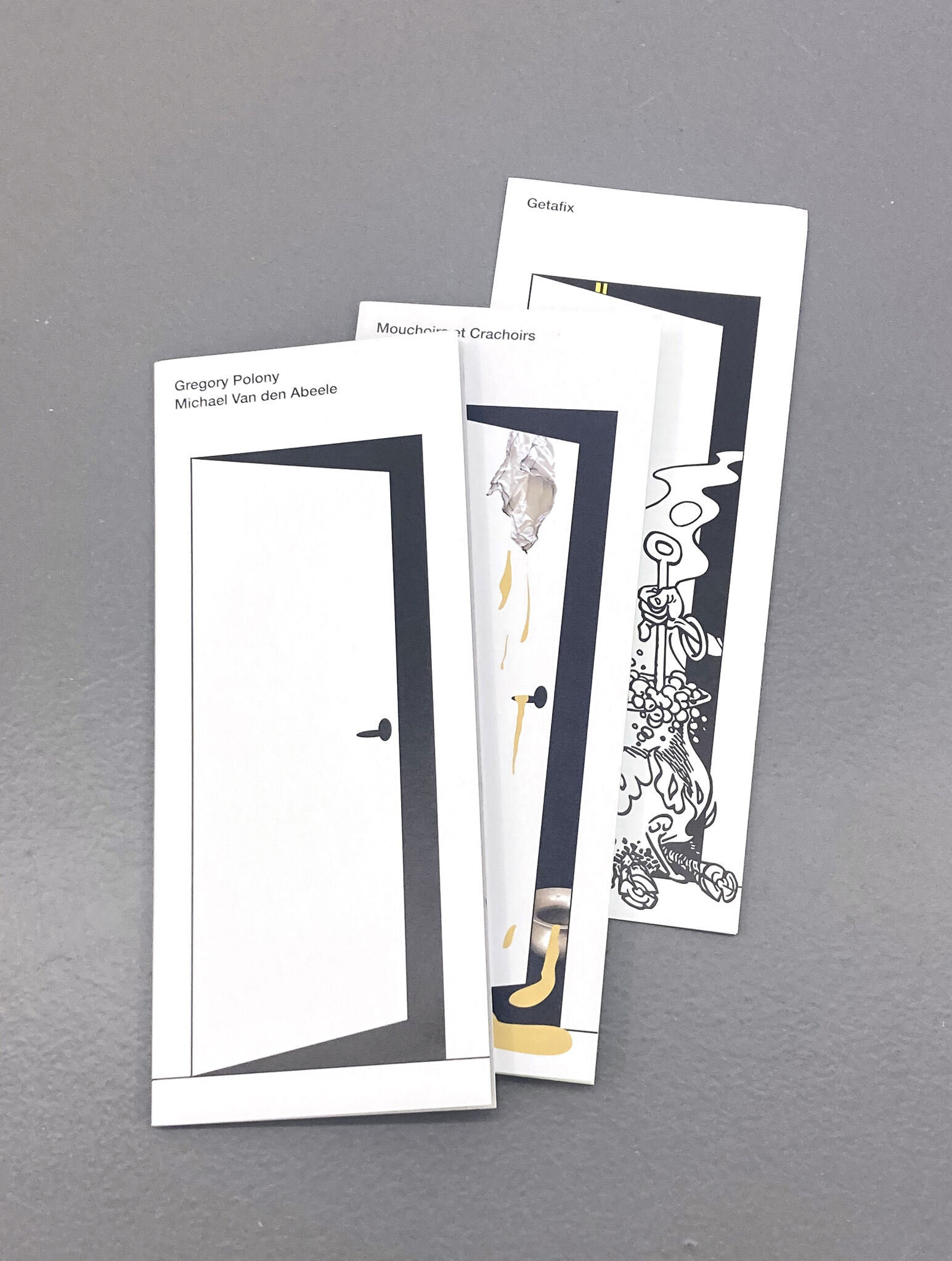

La deuxième partie de l’exposition de Fiona Mackay à la Salle de bains aménage une expérience de ses œuvres à l’exacte opposée. En cela, le simple accord au pluriel du titre, passant de Babe à Babes, est une apparence trompeuse parmi d’autres. Notons aussi que « babes », contrairement à son singulier, ne s’emploie pas comme une familiarité, ni un sobriquet à l’adresse de l’être désiré, ce qui donne une saveur iconoclaste à l’ajout de ce S.

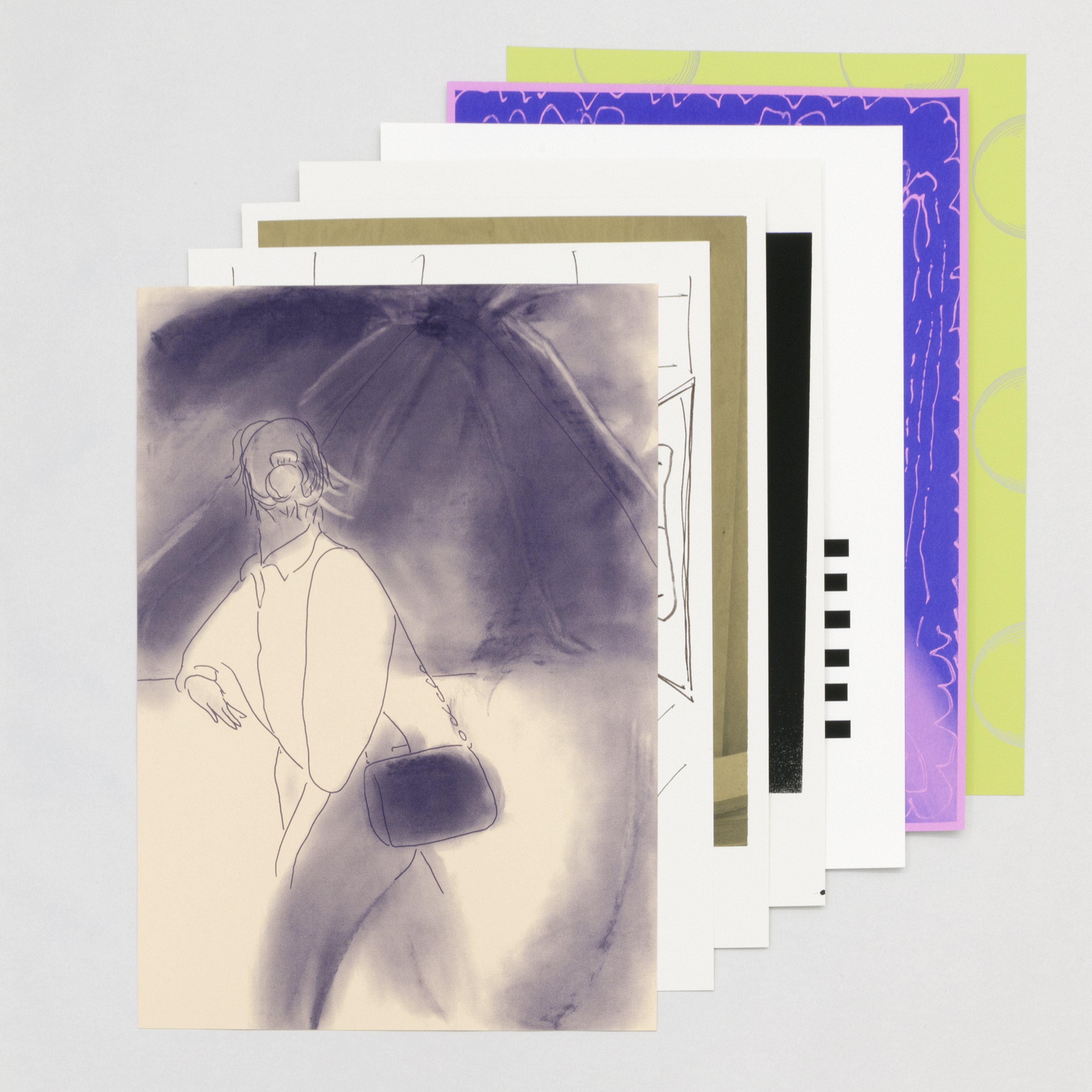

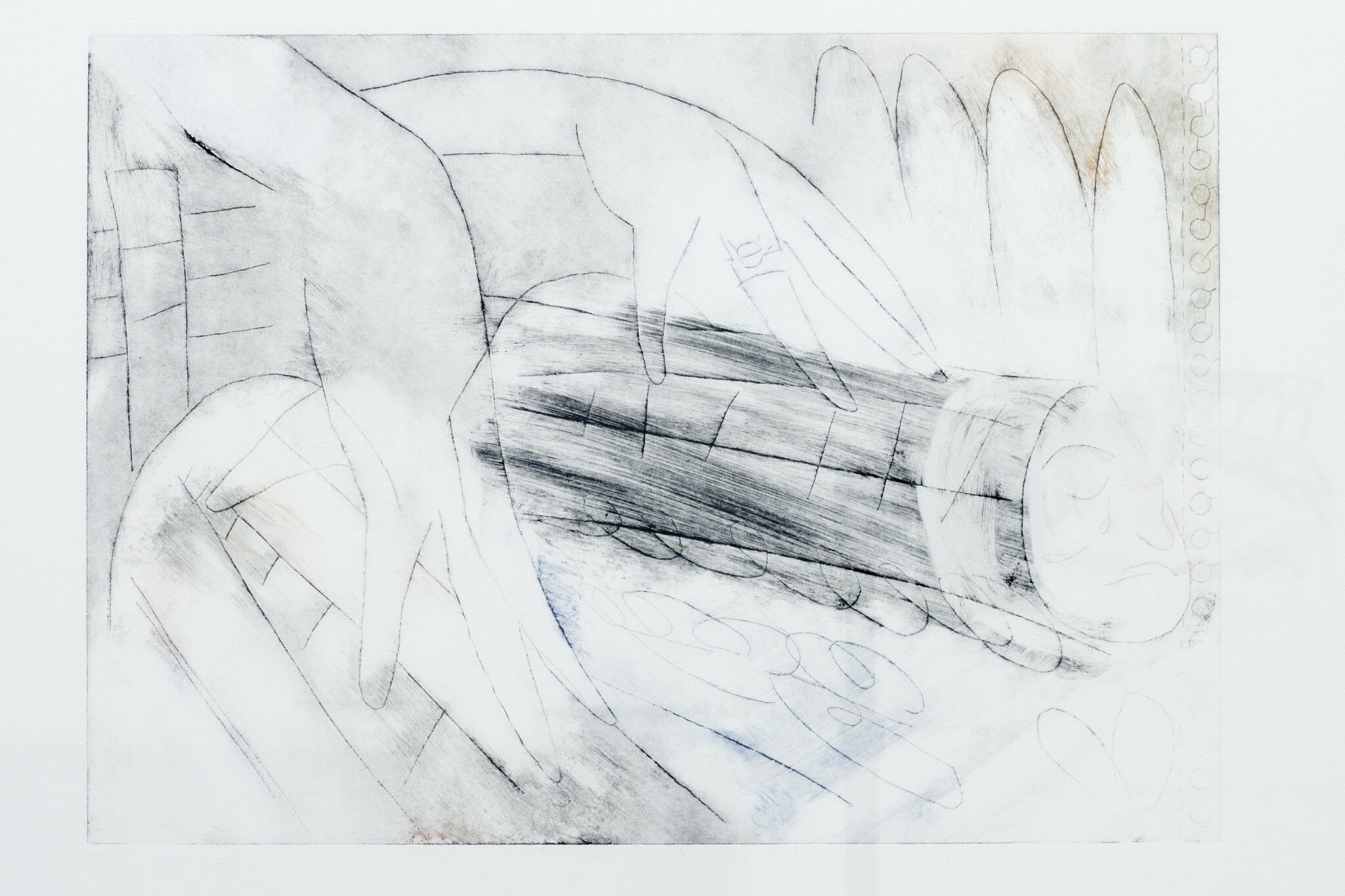

Mais l’introduction d’un trouble entre le pluriel et le singulier attire l’attention sur les relations complexes qu’entretiennent l’original et la copie dans une exposition qui a commencé par la diffusion massive de reproductions d’oeuvres dans l’espace public. Aussi, la technique de gravure employée par l’artiste (pointe sèche et monotype) laisse-t-elle le statut des œuvres dans un entre deux, entre l’unique et le multiple, la couleur étant redéposée sur la plaque à chaque passage sous presse. Cela peut donner à un même dessin des aspects extrêmement différents, selon la pâleur des encres ou la densité du pigment, comme un visage peut exprimer de manière terrifiante des variations d’humeur.

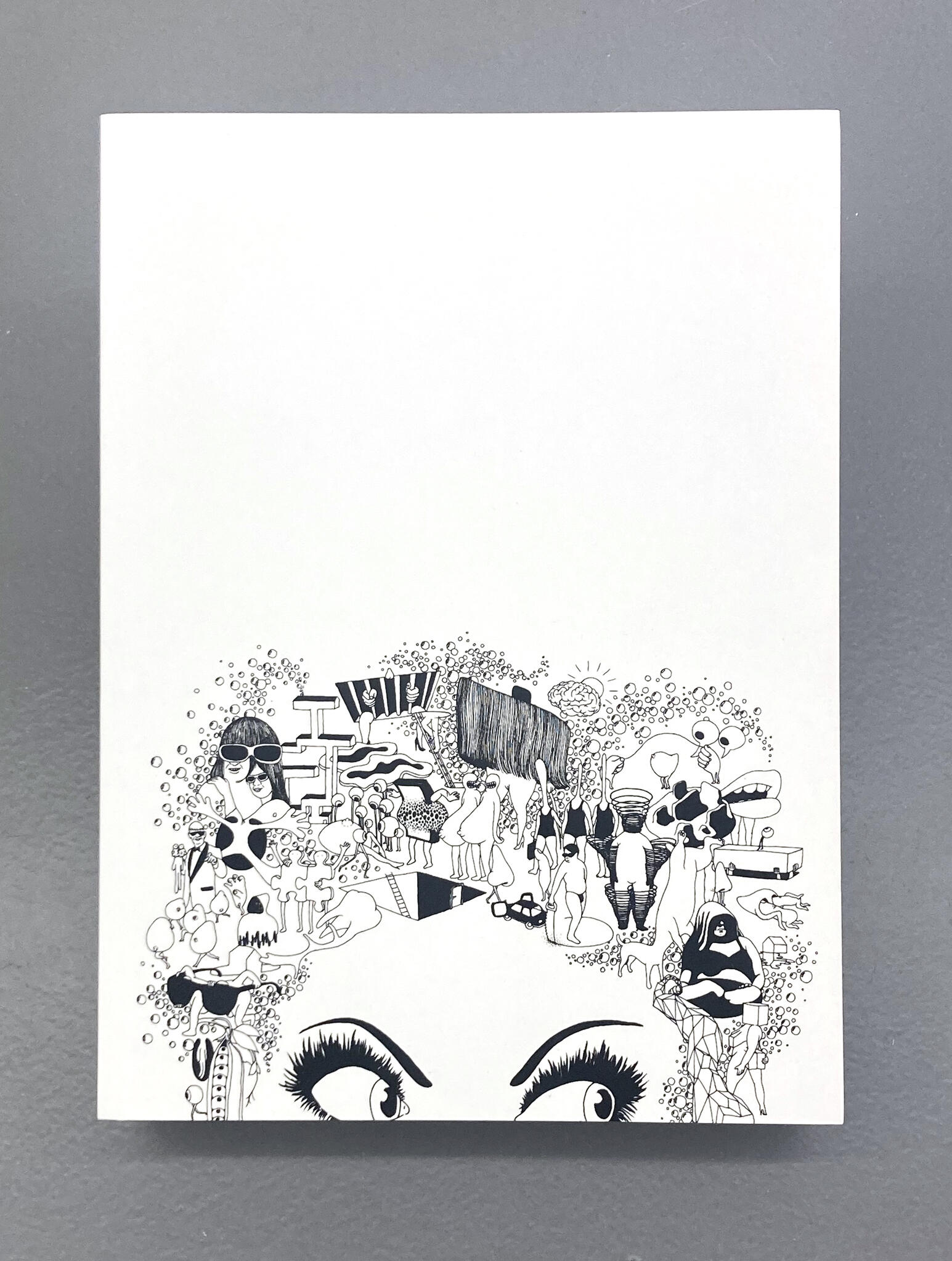

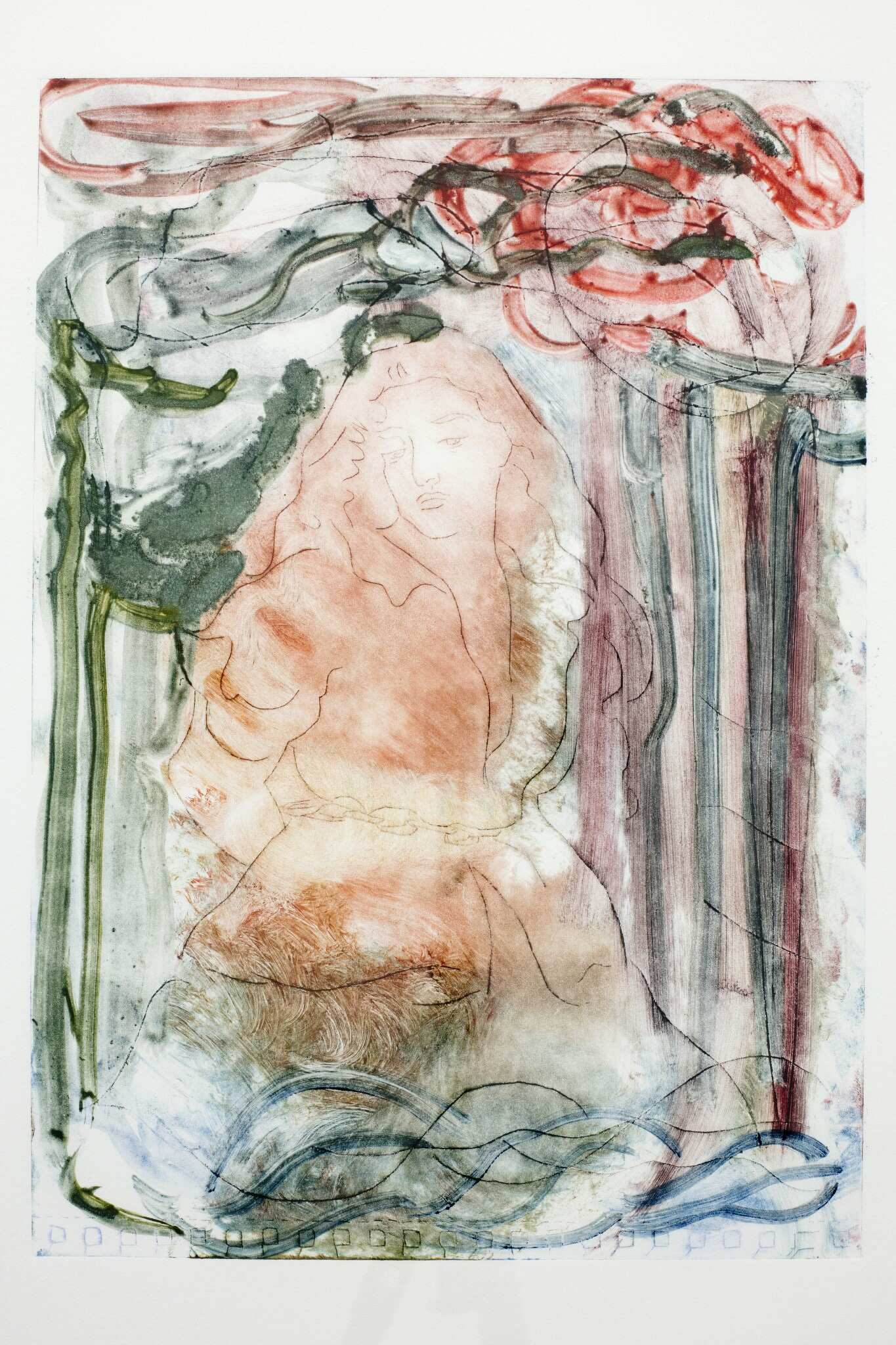

Celles qui traversent les six estampes montrées à la Salle de bains sont pour le moins ambivalentes, laissant d’autant plus ouvertes les interprétations de cette fable incomplète mettant en scène une jeune femme et un objet de désir. On pourra donc se méfier d’associer trop vite l’emprunt d’un style à un tempérament, qu’il en soit des traits cartoonesques de quelques figures descendantes de Lewis Carroll ou de la parenté de certaines scènes avec l’univers symboliste d’un Odilon Redon : une figure mélancolique pourrait aussi bien traduire un état de choc.

Ce qui est certain, c’est que la rêverie homo-érotique qui se laissait surprendre au détour d’une rue, a laissé place à une atmosphère plus froide pour abriter cette rencontre frontale avec les tirages originaux. De cette rencontre, le dispositif d’exposition particulie souligne les enjeux de manière un tantinet perverse, en obligeant le corps à accompagner l’action de regarder, quitte à répondre à cette attraction par un reflet incommodant.

La deuxième partie de l’exposition de Fiona Mackay à la Salle de bains aménage une expérience de ses œuvres à l’exacte opposée. En cela, le simple accord au pluriel du titre, passant de Babe à Babes, est une apparence trompeuse parmi d’autres. Notons aussi que « babes », contrairement à son singulier, ne s’emploie pas comme une familiarité, ni un sobriquet à l’adresse de l’être désiré, ce qui donne une saveur iconoclaste à l’ajout de ce S.

Mais l’introduction d’un trouble entre le pluriel et le singulier attire l’attention sur les relations complexes qu’entretiennent l’original et la copie dans une exposition qui a commencé par la diffusion massive de reproductions d’oeuvres dans l’espace public. Aussi, la technique de gravure employée par l’artiste (pointe sèche et monotype) laisse-t-elle le statut des œuvres dans un entre deux, entre l’unique et le multiple, la couleur étant redéposée sur la plaque à chaque passage sous presse. Cela peut donner à un même dessin des aspects extrêmement différents, selon la pâleur des encres ou la densité du pigment, comme un visage peut exprimer de manière terrifiante des variations d’humeur.

Celles qui traversent les six estampes montrées à la Salle de bains sont pour le moins ambivalentes, laissant d’autant plus ouvertes les interprétations de cette fable incomplète mettant en scène une jeune femme et un objet de désir. On pourra donc se méfier d’associer trop vite l’emprunt d’un style à un tempérament, qu’il en soit des traits cartoonesques de quelques figures descendantes de Lewis Carroll ou de la parenté de certaines scènes avec l’univers symboliste d’un Odilon Redon : une figure mélancolique pourrait aussi bien traduire un état de choc.

Ce qui est certain, c’est que la rêverie homo-érotique qui se laissait surprendre au détour d’une rue, a laissé place à une atmosphère plus froide pour abriter cette rencontre frontale avec les tirages originaux. De cette rencontre, le dispositif d’exposition particulie souligne les enjeux de manière un tantinet perverse, en obligeant le corps à accompagner l’action de regarder, quitte à répondre à cette attraction par un reflet incommodant.

The text introducing the last chapter conjured up the image of the guest artist in the solitude of her studio, completely immersed in a summer of intense work. During that time, in the sleepy streets of the city, posters sporadically appeared, although they displayed no written message; each week they distilled slightly erotic visions, like an intermittent story but also like a nonchalant communications initiative.

Depending on the day and hour, anyone could have surprised those figures of Apollo and Narcissus (sometimes the both of them together) still wet, freshly slapped up on their signboard, or puckering quite a lot from the heat and weather. Occasionally you would find them partly covered over by other ads, which these beautiful young men displayed, although they did contemptuously, as if such a foreign presence were an irreverence to their classic beauty.

The second part of the Fiona Mackay show at La Salle de bains lays out an experience of her work that is the exact opposite. In this case, the simple plural designation affixed to the title – Babe becoming Babes – is one of several misleading appearances. We should note, too, that “babes,” unlike the singular, isn’t used as a pet name for one’s “love object,” which lends an iconoclastic note to the addition of that ess.

Introducing a difficulty or confusion between the plural and the singular draws attention to the complex relationships that an original has with the copy in a show that began with the massive exposure in public of reproductions of works of art. Moreover, the engraving technique used by the artist (dry point and monotype) leaves the status of the artworks in limbo, an in-between state between the unique piece and the multiple, given that color is reapplied to the plate before each printing. This can give the same drawing extremely different looks according to the lightness of the inks or the density of the pigment, just as a face can express to a terrifying degree variations of mood.

Those running through the six prints on display at La Salle de bains are ambivalent at the very least, leaving all the more open our interpretations of an incomplete fable featuring a young woman and an object of desire. We might want to beware then of hastily associating the appropriation of a style with a certain temperament, be it the cartoonish traits of some figures descended from Lewis Carroll, or the kinship certain scenes have with the symbolist universe of an Odilon Redon. That is, a melancholic figure can just as well translate a state of shock.

What is certain though is that the homoerotic reverie that might seemingly pop up when you turn the next corner has given way to a chillier atmosphere for sheltering this head-on confrontation with the original editions. The exhibition’s specific display design underscores the issues surrounding that encounter in a way that is a tad perverse, forcing the body to go along with the act of looking, at the risk of responding to that attraction with an uncomfortable reflection.

translation: John O'Toole

Depending on the day and hour, anyone could have surprised those figures of Apollo and Narcissus (sometimes the both of them together) still wet, freshly slapped up on their signboard, or puckering quite a lot from the heat and weather. Occasionally you would find them partly covered over by other ads, which these beautiful young men displayed, although they did contemptuously, as if such a foreign presence were an irreverence to their classic beauty.

The second part of the Fiona Mackay show at La Salle de bains lays out an experience of her work that is the exact opposite. In this case, the simple plural designation affixed to the title – Babe becoming Babes – is one of several misleading appearances. We should note, too, that “babes,” unlike the singular, isn’t used as a pet name for one’s “love object,” which lends an iconoclastic note to the addition of that ess.

Introducing a difficulty or confusion between the plural and the singular draws attention to the complex relationships that an original has with the copy in a show that began with the massive exposure in public of reproductions of works of art. Moreover, the engraving technique used by the artist (dry point and monotype) leaves the status of the artworks in limbo, an in-between state between the unique piece and the multiple, given that color is reapplied to the plate before each printing. This can give the same drawing extremely different looks according to the lightness of the inks or the density of the pigment, just as a face can express to a terrifying degree variations of mood.

Those running through the six prints on display at La Salle de bains are ambivalent at the very least, leaving all the more open our interpretations of an incomplete fable featuring a young woman and an object of desire. We might want to beware then of hastily associating the appropriation of a style with a certain temperament, be it the cartoonish traits of some figures descended from Lewis Carroll, or the kinship certain scenes have with the symbolist universe of an Odilon Redon. That is, a melancholic figure can just as well translate a state of shock.

What is certain though is that the homoerotic reverie that might seemingly pop up when you turn the next corner has given way to a chillier atmosphere for sheltering this head-on confrontation with the original editions. The exhibition’s specific display design underscores the issues surrounding that encounter in a way that is a tad perverse, forcing the body to go along with the act of looking, at the risk of responding to that attraction with an uncomfortable reflection.

translation: John O'Toole

Liste des œuvres :

List of works :

de gauche à droite,

For real, 2021

pointe sèche et monotype sur papier

Valium, 2021

pointe sèche et monotype sur papier

Fortune and promise, 2021

pointe sèche et monotype sur papier

A young age, 2021

pointe sèche et monotype sur papier

Always summer (never winter), 2021

pointe sèche et monotype sur papier

Scandal, 2021

pointe sèche et monotype sur papier

For real, 2021

pointe sèche et monotype sur papier

Valium, 2021

pointe sèche et monotype sur papier

Fortune and promise, 2021

pointe sèche et monotype sur papier

A young age, 2021

pointe sèche et monotype sur papier

Always summer (never winter), 2021

pointe sèche et monotype sur papier

Scandal, 2021

pointe sèche et monotype sur papier

from left to right,

For real, 2021

drypoint and monotype on paper

Valium, 2021

drypoint and monotype on paper

Fortune and promise, 2021

drypoint and monotype on paper

A young age, 2021

drypoint and monotype on paper

Always summer (never winter), 2021

drypoint and monotype on paper

Scandal, 2021

drypoint and monotype on paper

For real, 2021

drypoint and monotype on paper

Valium, 2021

drypoint and monotype on paper

Fortune and promise, 2021

drypoint and monotype on paper

A young age, 2021

drypoint and monotype on paper

Always summer (never winter), 2021

drypoint and monotype on paper

Scandal, 2021

drypoint and monotype on paper

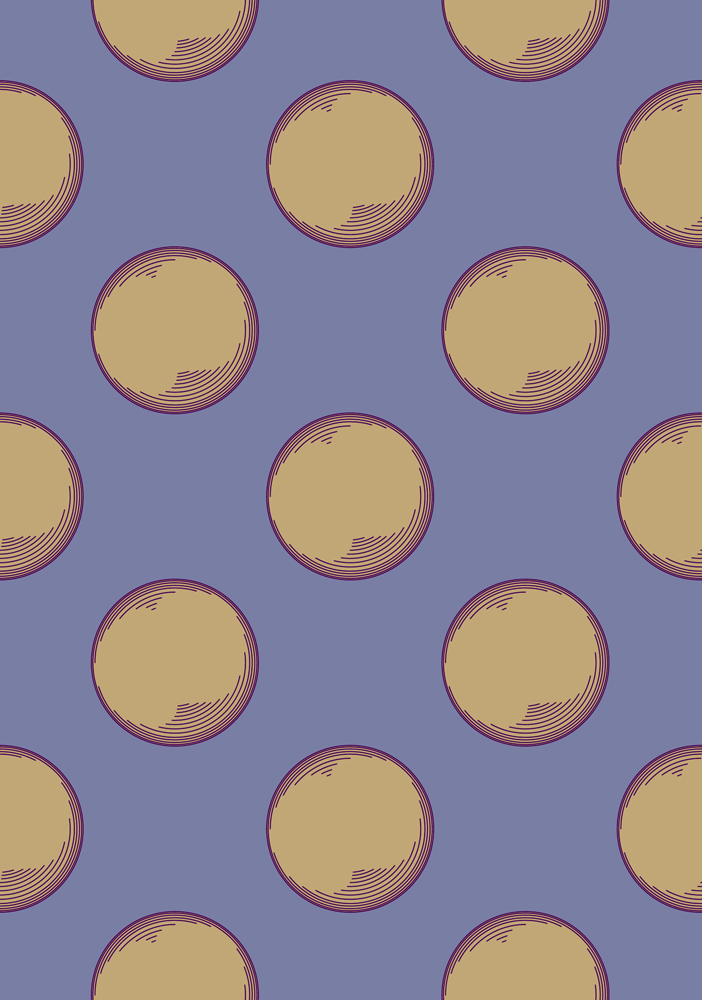

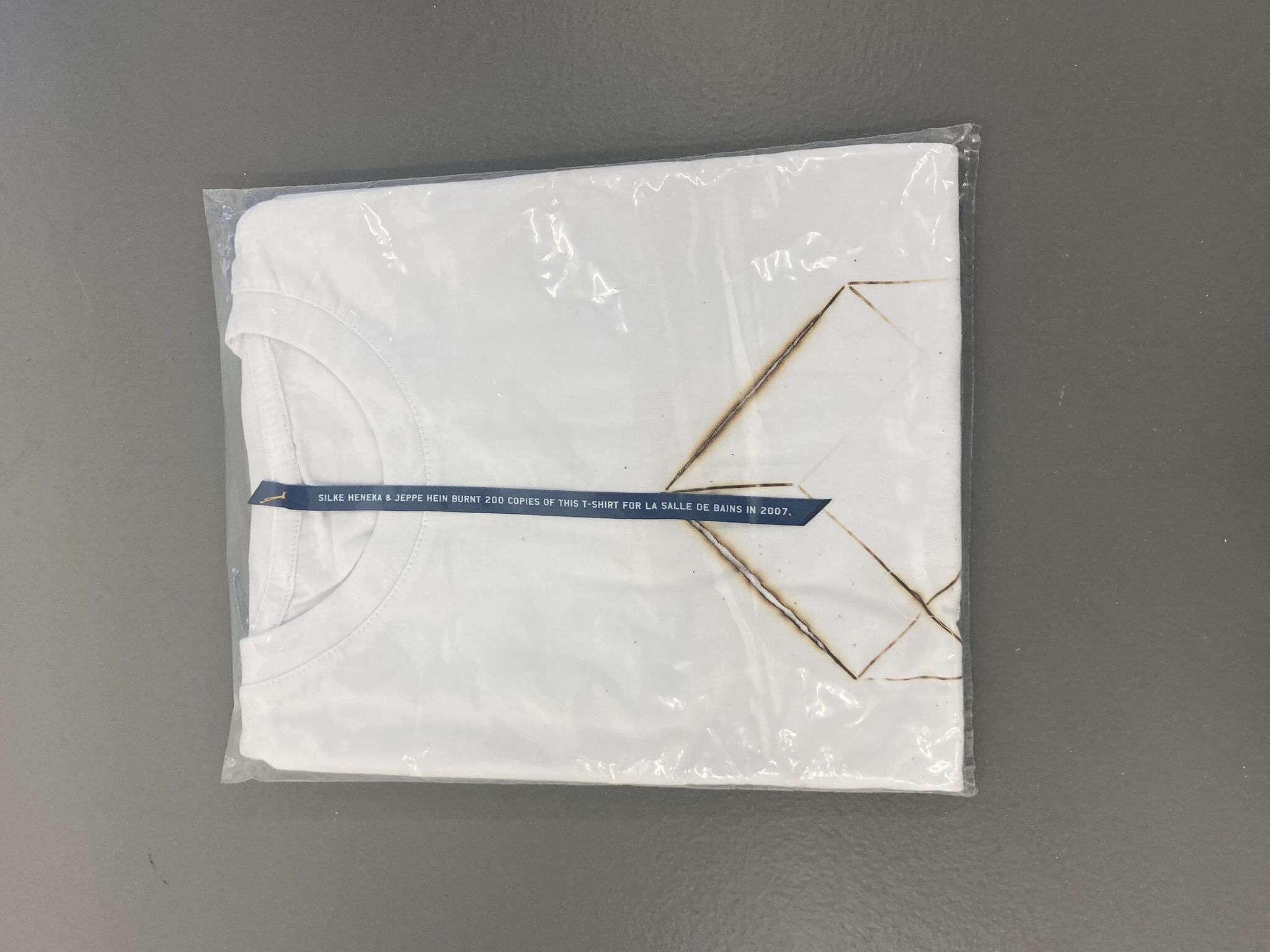

Babes, 2021

Affiche

Fiona Mackay (1984, Aberdeen, Ecosse), vit et travaille à Marseille.

Diplômée de la Glasgow School of Art (2006), Fiona Mackay a participé à de nombreuses expositions personnelles et collectives partout en Europe : opium, Belsunce projects, Marseille (2021) ; La psychologie des serrures, CAN, Neuchâtel (2020) ; dreams, Klemm’s, Berlin (2019) ; Running Away, New Joerg, Vienne (2018) ; Ether, Une, une, une, Perpignan (2018) ; prolog, Apes&castels, Bruxelles (2017) ; Foreign Place, WIELS, Bruxelles (2016)

Diplômée de la Glasgow School of Art (2006), Fiona Mackay a participé à de nombreuses expositions personnelles et collectives partout en Europe : opium, Belsunce projects, Marseille (2021) ; La psychologie des serrures, CAN, Neuchâtel (2020) ; dreams, Klemm’s, Berlin (2019) ; Running Away, New Joerg, Vienne (2018) ; Ether, Une, une, une, Perpignan (2018) ; prolog, Apes&castels, Bruxelles (2017) ; Foreign Place, WIELS, Bruxelles (2016)

Fiona Mackay (1984, Aberdeen, Scotland), lives and works in Marseille. A graduate of the Glasgow School of Art (2006), Mackay has taken part in numerous group and solo shows throughout Europe: opium, Belsunce projects, Marseille (2021) ; La psychologie des serrures, CAN, Neuchâtel (2020) ; dreams, Klemm’s, Berlin (2019) ; Running Away, New Joerg, Vienna (2018) ; Ether, Une, une, une, Perpignan (2018) ; prolog, Apes&castels, Brussels (2017) ; Foreign Place, WIELS, Brussels (2016)

La Salle de bains reçoit le soutien du Ministère de la Culture DRAC Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes,

de la Région Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes et de la Ville de Lyon.

de la Région Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes et de la Ville de Lyon.