Photo : Jesús Alberto Benitez

Photo : Jesús Alberto Benitez

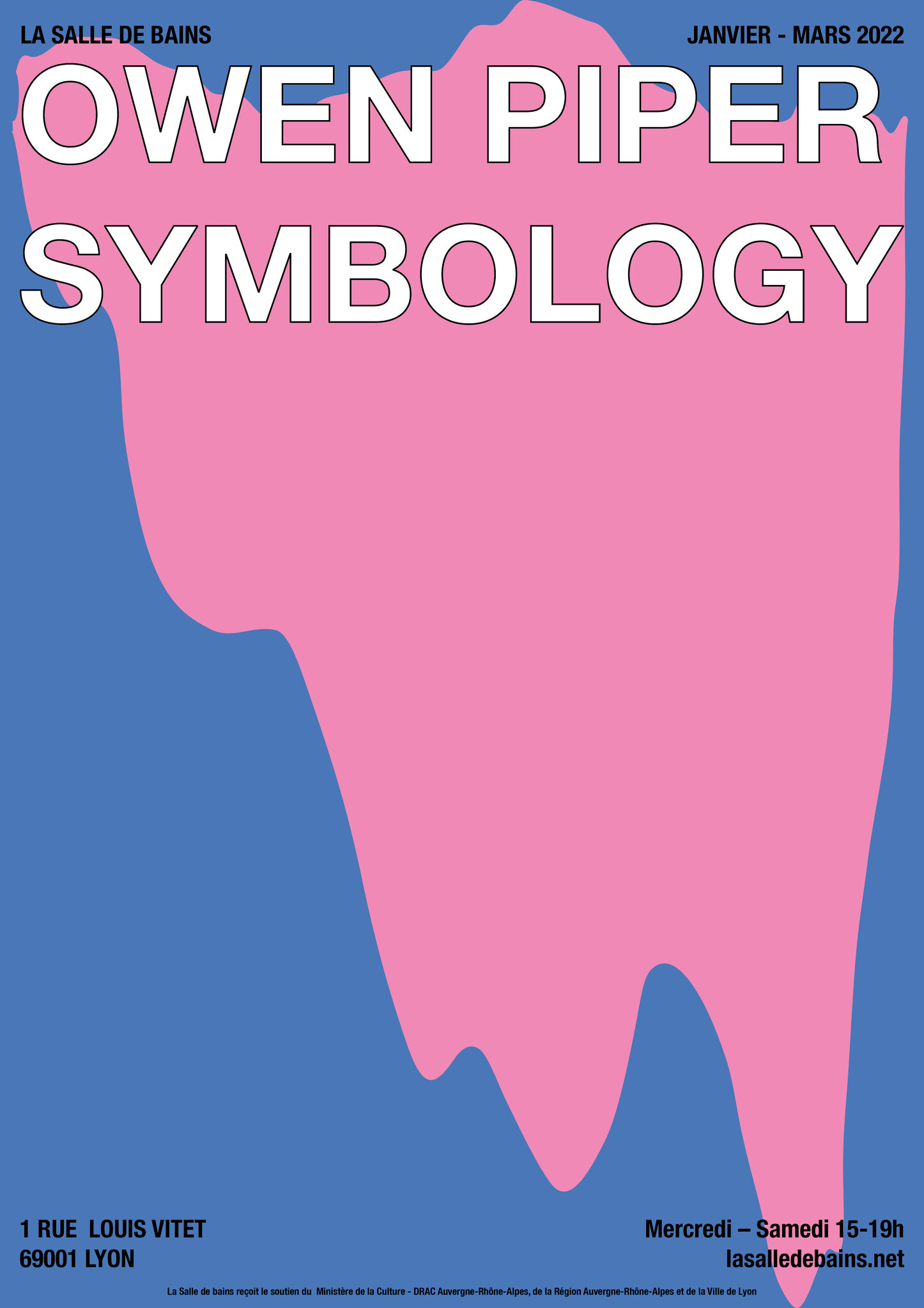

Symbology - salle 2

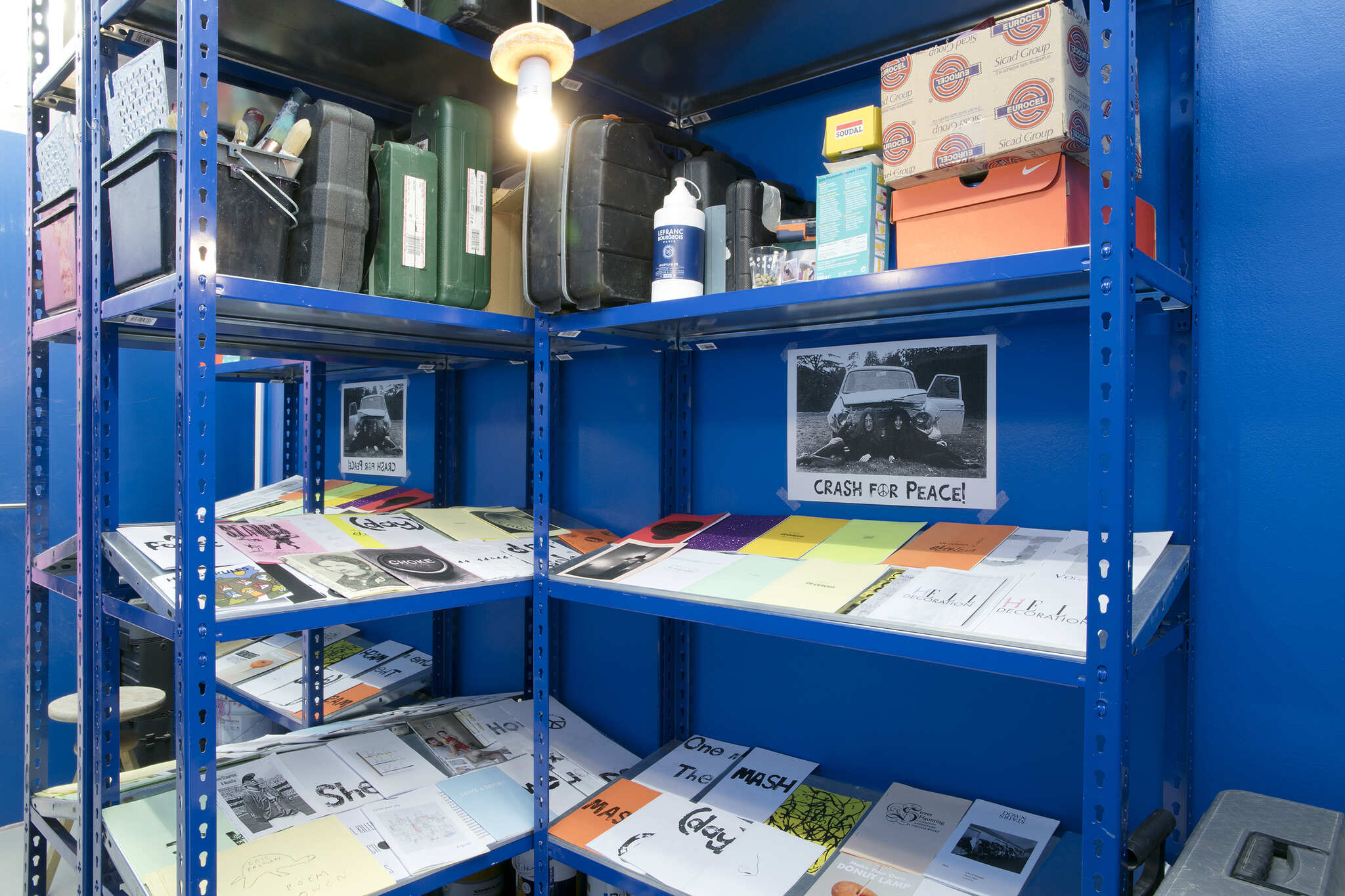

L’épisode précédent se passait dans une exposition de peintures d’Owen Piper. Elle offrait un petit aperçu d’une production extrêmement abondante, indiquant quelques aspects de la méthode de travail, comme le collage d’images ou d’objets pauvres trouvés dans l’environnement quotidien. Elle renseignait aussi sur quelques-uns des thèmes récurrents de l’œuvre, en particulier l’irrémédiable autoréférentialité de la peinture en même temps que ses envieuses aspirations pour le cinéma. La présentation était assez conventionnelle, à l’exception des cimaises peintes en bleu sur la moitié de l’espace d’exposition, ce dernier en partie encombré par les étagères déplacées de la réserve, celle-ci transformée en petite salle de projection. Tandis que tout l’outillage nécessaire à sa production avait glissé sur la scène même de l’exposition, à sa place, un film passait en revue des séquences de peinture en bâtiment soulignant le caractère poétique, politique ou tactique de l’acte de peindre (de Mister Bean à Clint Eastwood dans L’Homme des hautes plaines, en passant par la cellule syndicale dans Tout va bien de Jean-Luc Godard), le tout sous les auspices de la Panthère rose dans The Pink Phink (1964) qui célèbre la victoire du rose sur le bleu dans une véritable guerre de territoire.

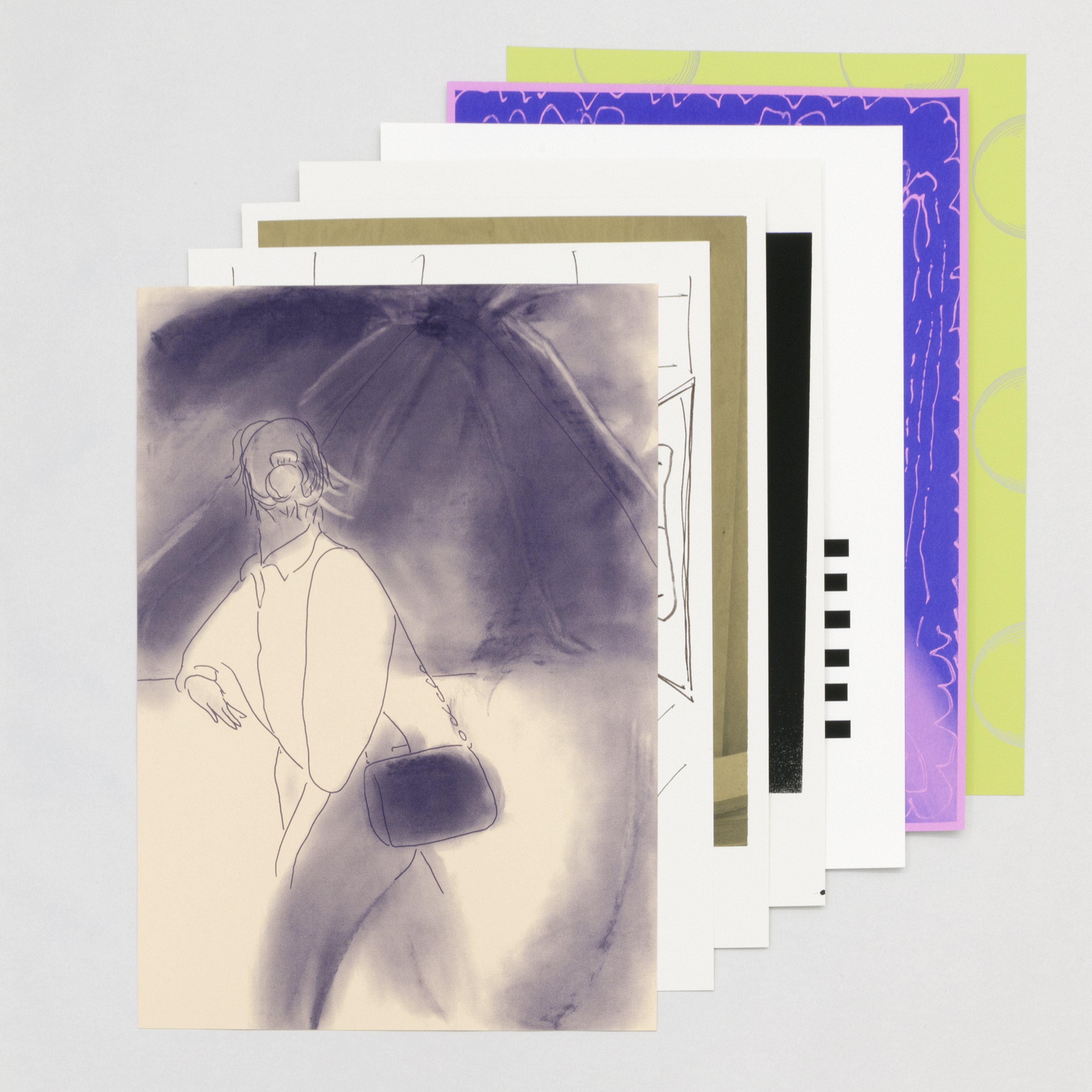

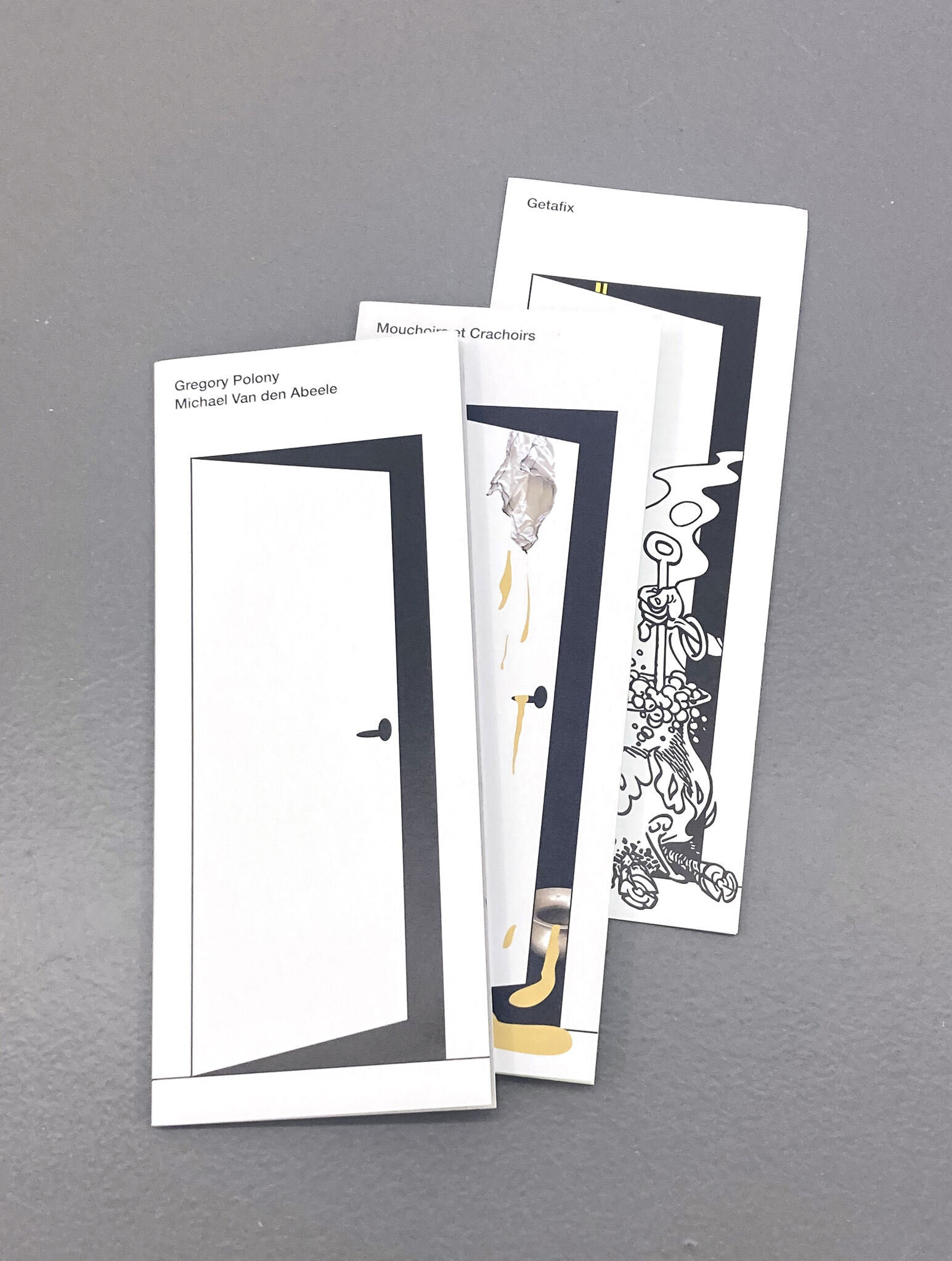

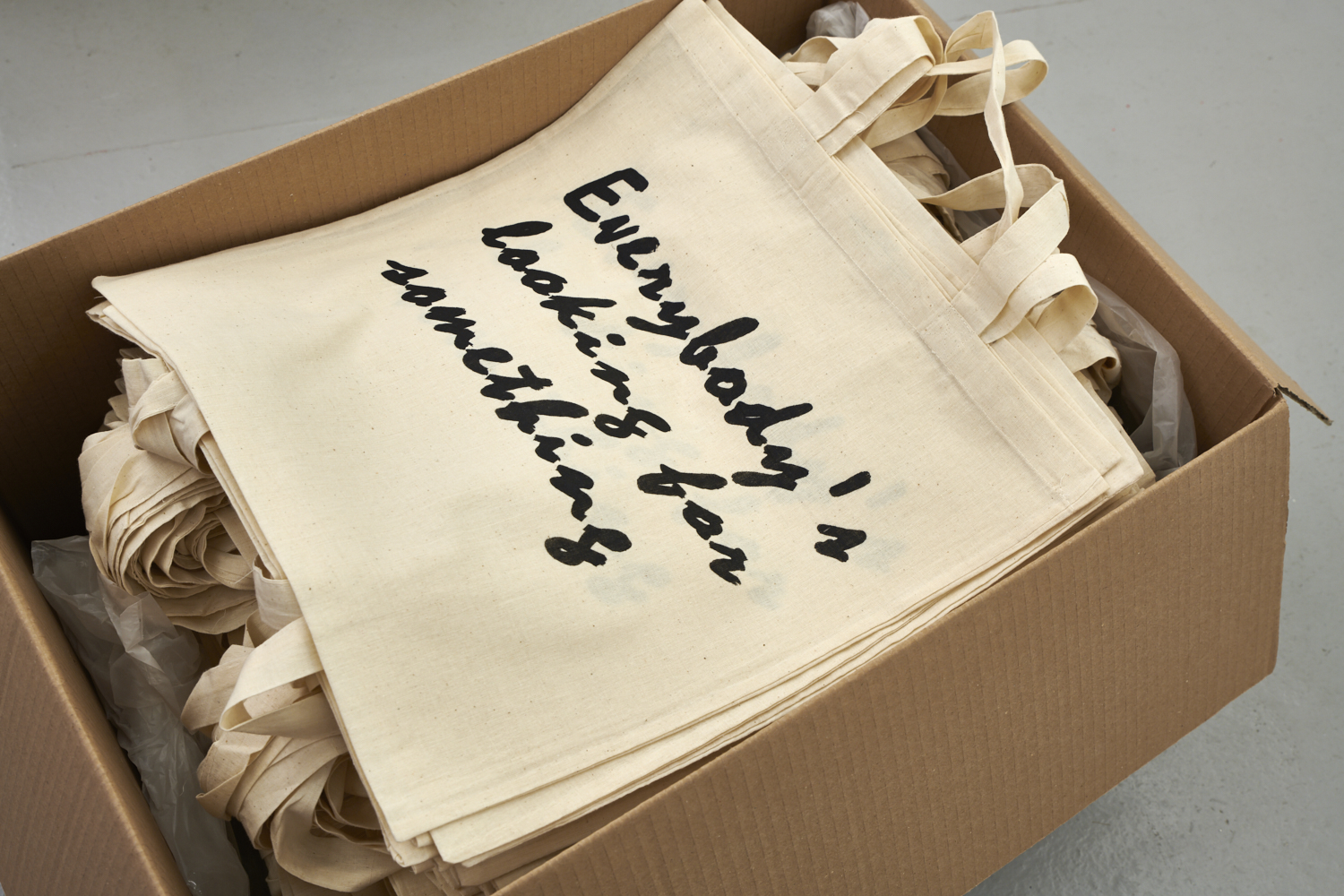

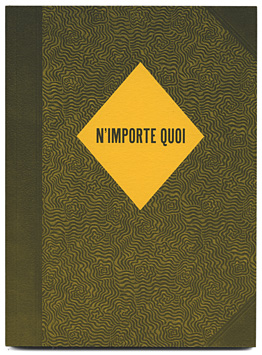

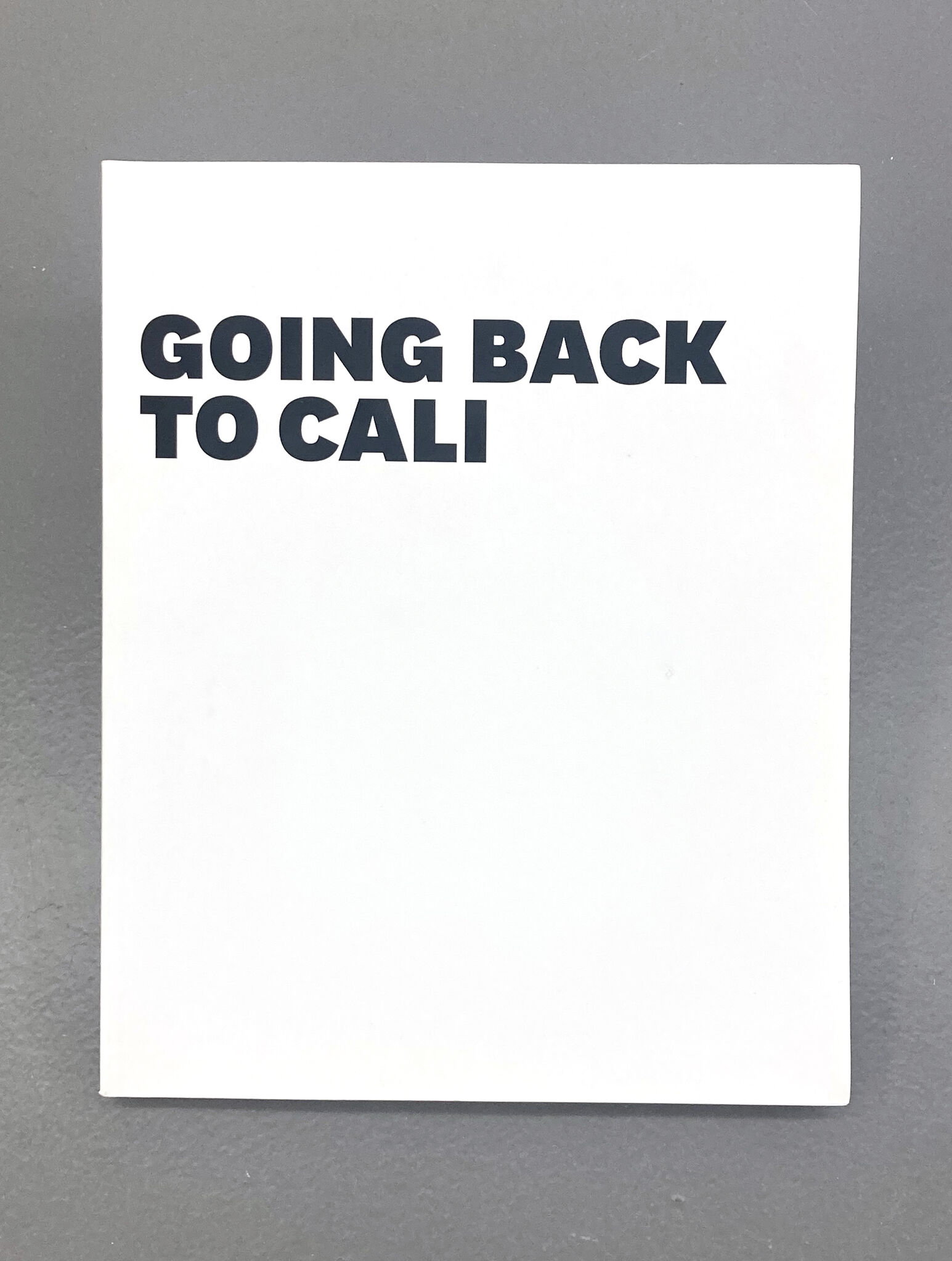

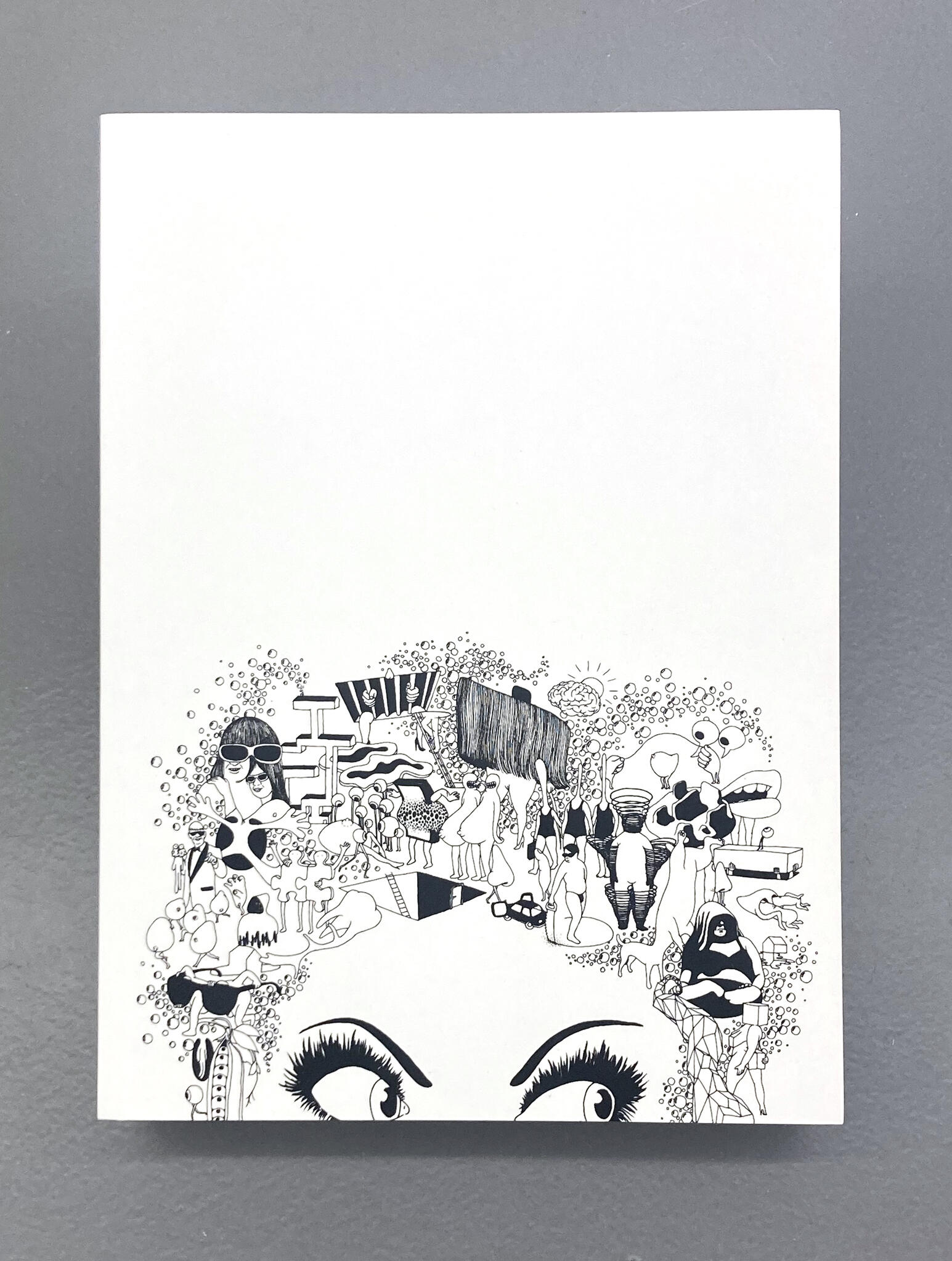

Voilà pour le résumé. Le scénario de la deuxième salle de l’exposition d’Owen Piper à la Salle de bains, quant à lui, est centré sur le travail d’édition, non moins prolifique, tout aussi modeste dans ses moyens et non moins séparé de la vie quotidienne de l’artiste. Ainsi pourra-t-on y croiser des membres de la famille, des ami.e.s artistes ou auteur.ice.s, comme des figures littéraires (avec une préférence pour le flâneur) ou médiatiques (avec une préférence pour les stars au destin tragique qu’ont produites les années 1960 et reproduites en masse les années 1980-90). Comme ses peintures, les éditions d’Owen Piper se distinguent par leur caractère fait main jusque dans leur diffusion (par les maisons d’auto-édition Maris Piper Press ou Jolly Good books), utilisant exclusivement le photocopieur ou l’imprimante de bureau pour des raisons économiques qui ont elles-mêmes à voir avec des raisons politiques. Ces zines ont aussi en commun avec les peintures de procéder par assemblage, rapprochements aléatoires voire impulsifs dont la relation texte-image est le théâtre, sans pour autant que le geste d’appropriation (d’œuvres ou de textes le plus souvent copiés dans leur intégralité) ne soit revendiqué comme un acte subversif – ce qui à l’heure actuelle serait déplacé – mais comme un comportement inné, un jeu d’enfant.

Pour toutes ces raisons, la pratique de la microédition chez Owen Piper prolonge aussi une certaine tradition du medium – où l’héritage de l’art conceptuel et de la culture punk est rendu visible – tout en étant le vecteur d’une réflexion sur ce qu’il reste des utopies de la modernité et des mouvements d’émancipation de la deuxième moitié du XXe siècle dans l’ère numérique et à l’heure où la philosophie du do it yourself se perpétue dans le meuble en kit et le développement personnel. Mais nous n’avons pas affaire à un tempérament nostalgique, en témoigne l’énergie déployée dans cette hyperproduction dont la générosité va jusqu’à proposer plusieurs expositions en une, rattrapant un projet antérieur annulé à cause de la pandémie dans la présentation d’une version miniature (Grow the Revolution, qui devait avoir lieu à la Salle de bains en même temps que la mise en œuvre du Brexit). S’il fallait qualifier l’humeur dont est teintée l’œuvre d’Owen Piper, elle serait plutôt ambivalente, comme revenue de l’épuisement de ses moyens et de la croyance en des vertus transcendantales de l’art, mais continuant sans relâche – et avec beaucoup d’humour – à produire des objets qui vont à leur tour créer des espaces de rencontre et de partage, comme l’est un projet éditorial. Issu d’une collaboration avec David Bellingham, le poster distribué pendant l’exposition signale en code morse et à la pomme de terre : « travaux en cours ».

The preceding iteration took place in a show featuring Owen Piper’s paintings. That exhibition afforded a small preview of an extremely extensive output and pointed up several aspects of the artist’s way of working, like the collage of images and humble objects found in normal

day-to-day surroundings. It also told us about a few of the recurrent themes running through the work, especially painting’s irreparable self-referentiality along with its jealous aspirations for the cinema. The presentation was fairly conventional, except for the walls displaying the works, painted blue in half the exhibition space. The latter was, moreover, partly blocked by the shelving units removed from the storage room, which had been in turn transformed into a screening room. While all the equipment required to produce the show literally slipped through the space of the display to its appointed position, in its place a film was screened that went over sequences of house painting that underscored the poetic, political, and tactical character of the act of painting (from Mister Bean to Clint Eastwood in High Plains Drifter and the labor union committee in Godard’s Tout va bien), all of this under the auspices of the Pink Panther in The Pink Phink (1964), which celebrates the victory of pink over blue in a veritable turf war.

So much for the summary.

The story of the second gallery of the Owen Piper show at La Salle de bains is centered on the editorial work, no less prolific, just as modest in its means, and no less separate from the artist’s day-to-day life. There visitors will run into Piper’s family members, artist friends and writers, as well as literary figures (with a preference for the flâneur) and media personalities (with a preference for the stars with tragic lives that the 1960s produced and the 1980s and ‘90s reproduced en masse). As with the artist’s paintings, Owen Piper editions stand out for their handmade character, right down to their distribution (by the self-publishing houses Maris Piper Press and Jolly Good Books), exclusively using the photocopying machine or office printer for economic reasons that also have something to do with political ones. These zines have something in common with the paintings, too, i.e., they take shape through assemblage and random, even impulsive parallels, the theater of which is the relationship of the text to the image – but without the gesture of appropriation (of works or text, most often copied out in their entirety) being touted as a subversive act. At present, that would be uncalled for. The gesture is rather given out as innate behavior, child’s play.

For all these reasons, the practice of micro-editions in Piper’s art extends a certain tradition of the medium as well, where the legacy of conceptual art and punk culture is made visible. And that practice is a vector, too, of Piper’s reflection on what remains of the utopias littering modernity and the liberation movements of the second half of the 20th century in the digital age and at a time when the DIY philosophy is carried on in ready-to-assemble furniture and personal development. Yet what we have here is not a nostalgic temperament. We only need to think about the energy involved in this hyperproduction whose generosity goes so far as to offer several shows in one, making up for an earlier project – canceled because of the pandemic – now on view in a miniature version (Grow the Revolution, that ought to have taken place at La Salle de bains at the same time Brexit was going into effect). If we had to characterize the mood of Piper’s work throughout, it would be ambivalent, as if it had been brought back from its exhausted means and the belief in the transcendental virtues of art, yet continuing without respite – and with lots of humor – to produce objects that will in turn create spaces for meeting others and sharing, just as a publishing project does. The result of a collaboration with David Bellingham, the poster distributed during the show indicates “work in progress” in Morse code using a potato stamp.

translation : John O'Toole

Liste des œuvres :

List of works :

Bonsaï, 2022

peinture sur toile, collage sur poster

Green cancelled painting, 2021

collage et peinture sur toile

Jacket, 2020

peinture sur veste

Oakleaf, 2021

peinture sur toile

The Bosman series, 2015-2020

11 fanzines, impression laser sur papier, format A5,

The great toe, 2021

peinture sur toile

Bi-Furious, 2021

peinture sur toile

Untitled work, 2022

peinture sur toile

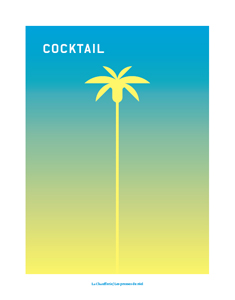

Tu aimes mon affiche ?, 2019

poster

Ensemble de publications, 2015-2022

Donut lamp, 2019/2022

ampoule et donut

Grow the revolution, 2021

poster

12th February to 17th February, 2022

collage

Hanging Light, 2022

ampoule et peinture sur vinyle

Grow the revolution, 2022

maquette, matériaux divers et poster

Iloveyouall, 2022

poster,

Badge, 2015

badge

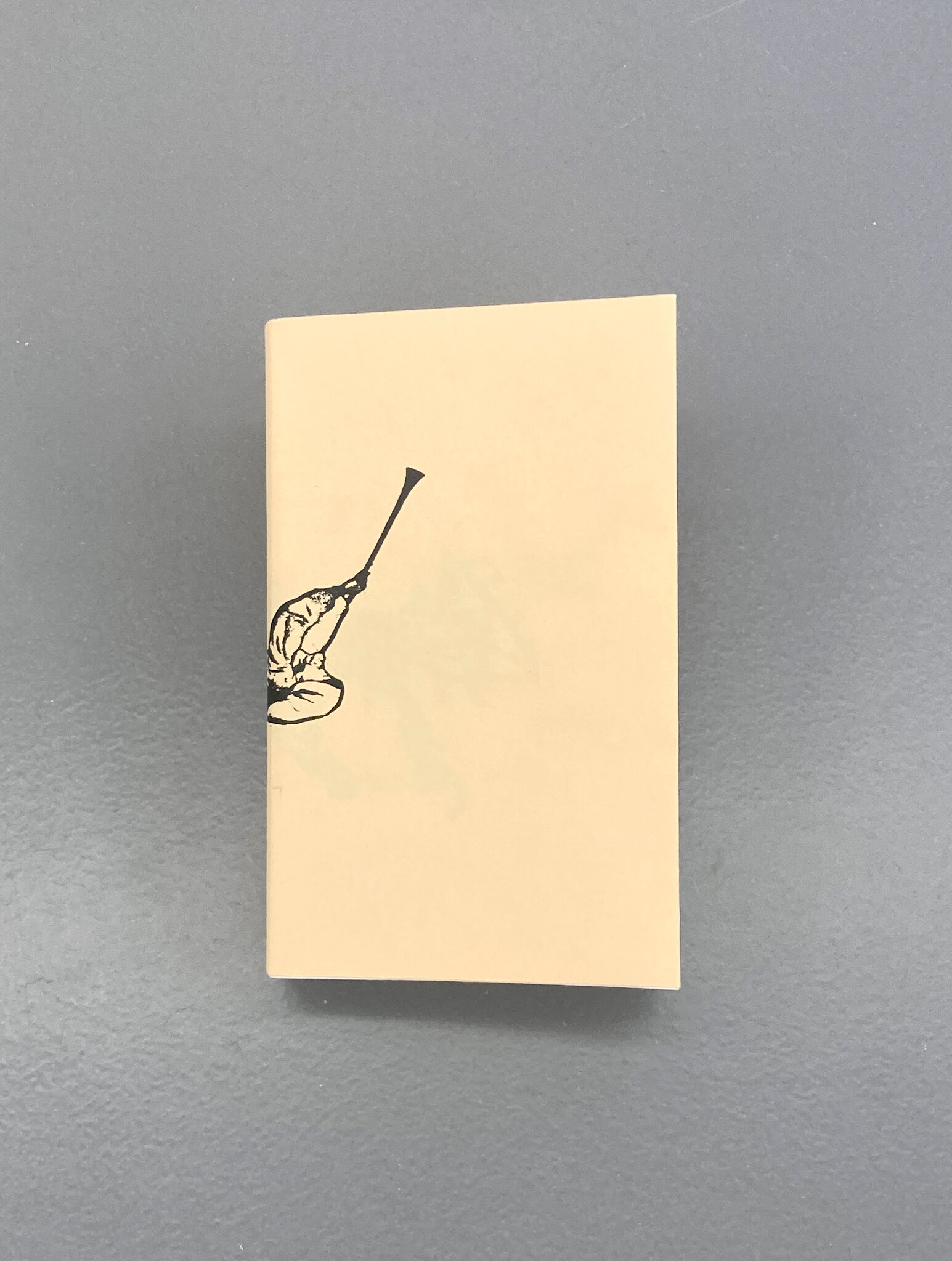

Jolly Good books, 2015-2022

fanzines

Technologies of the self, 2022

peinture sur toile

Joni does it with her teeth, 2022

peinture sur toile

Hofner ignition violin bass, Star-club, Hamburg 1962, 2022

peinture sur toile

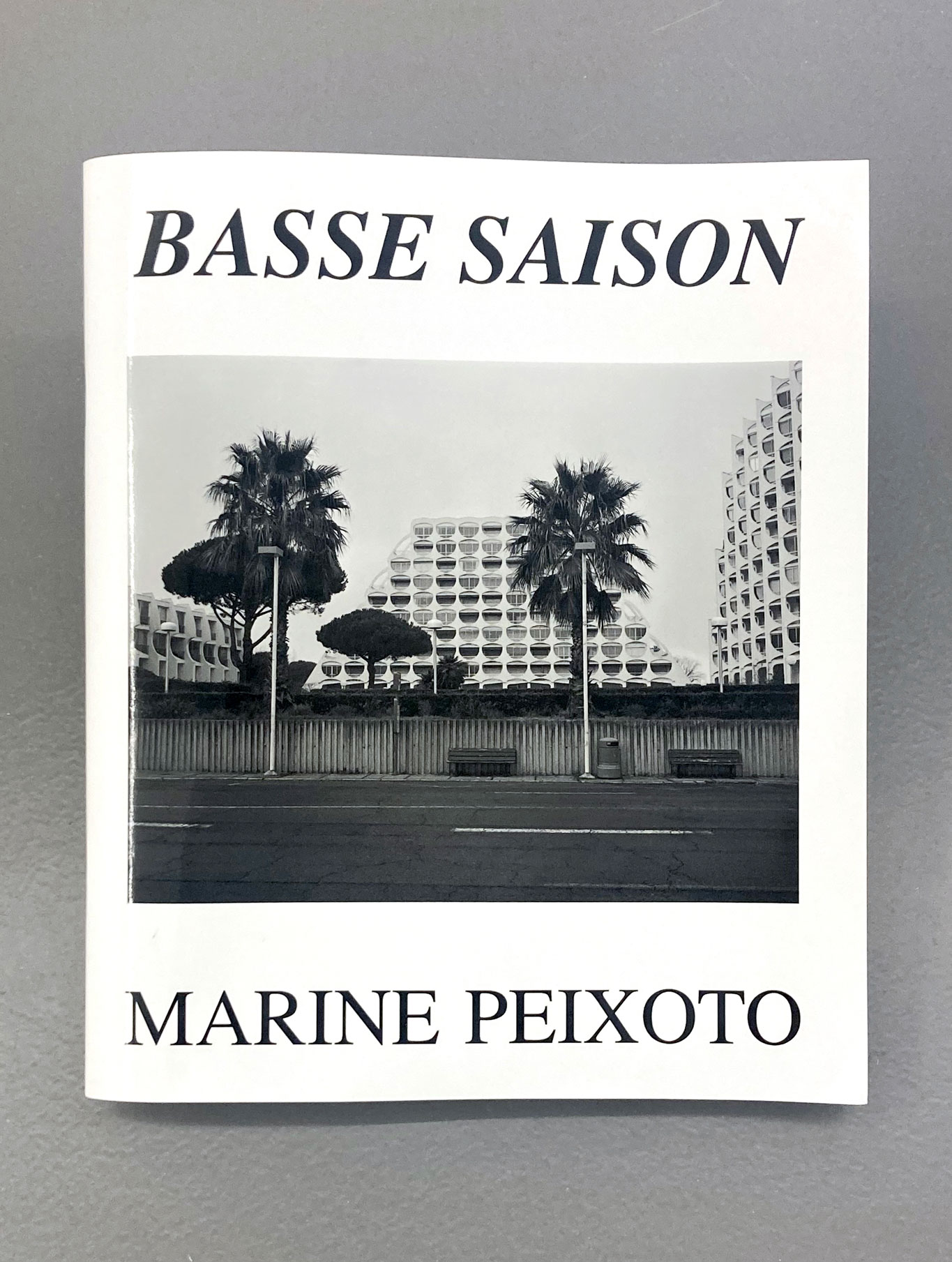

Sélection de publications récentes, 2021-2022

fanzines et photocopies

Bonsaï, 2022

painting on canvas, collage on poster

Green cancelled painting, 2021

collage and painting on canvas

Jacket, 2020

painting on jacket

Oakleaf, 2021

painting on canvas

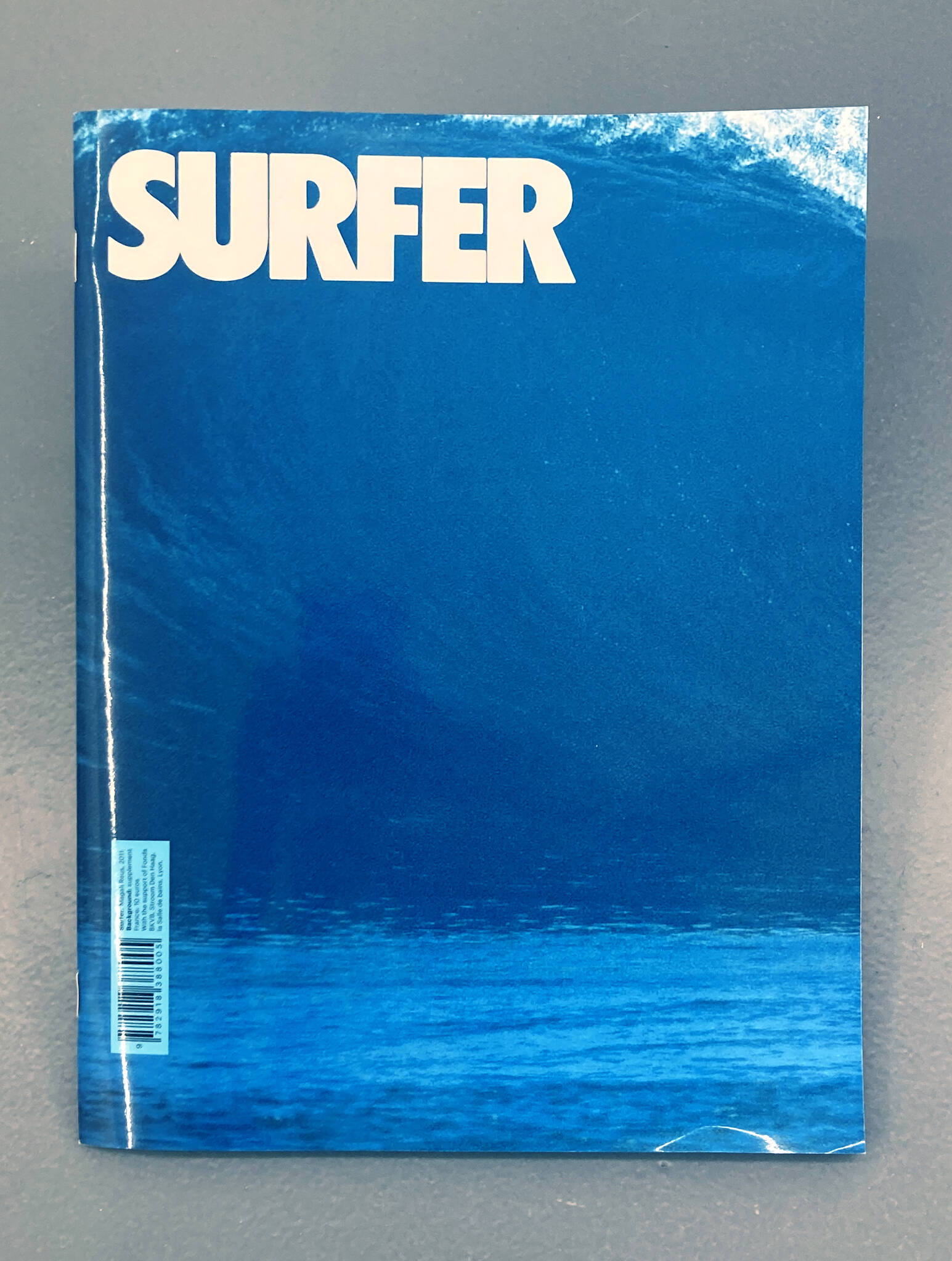

The Bosman series, 2015-2020

A5 fanzines

The great toe, 2021

painting on canvas

Bi-Furious, 2021

painting on canvas

Untitled work, 2022

painting on canvas

Tu aimes mon affiche ?, 2019

poster

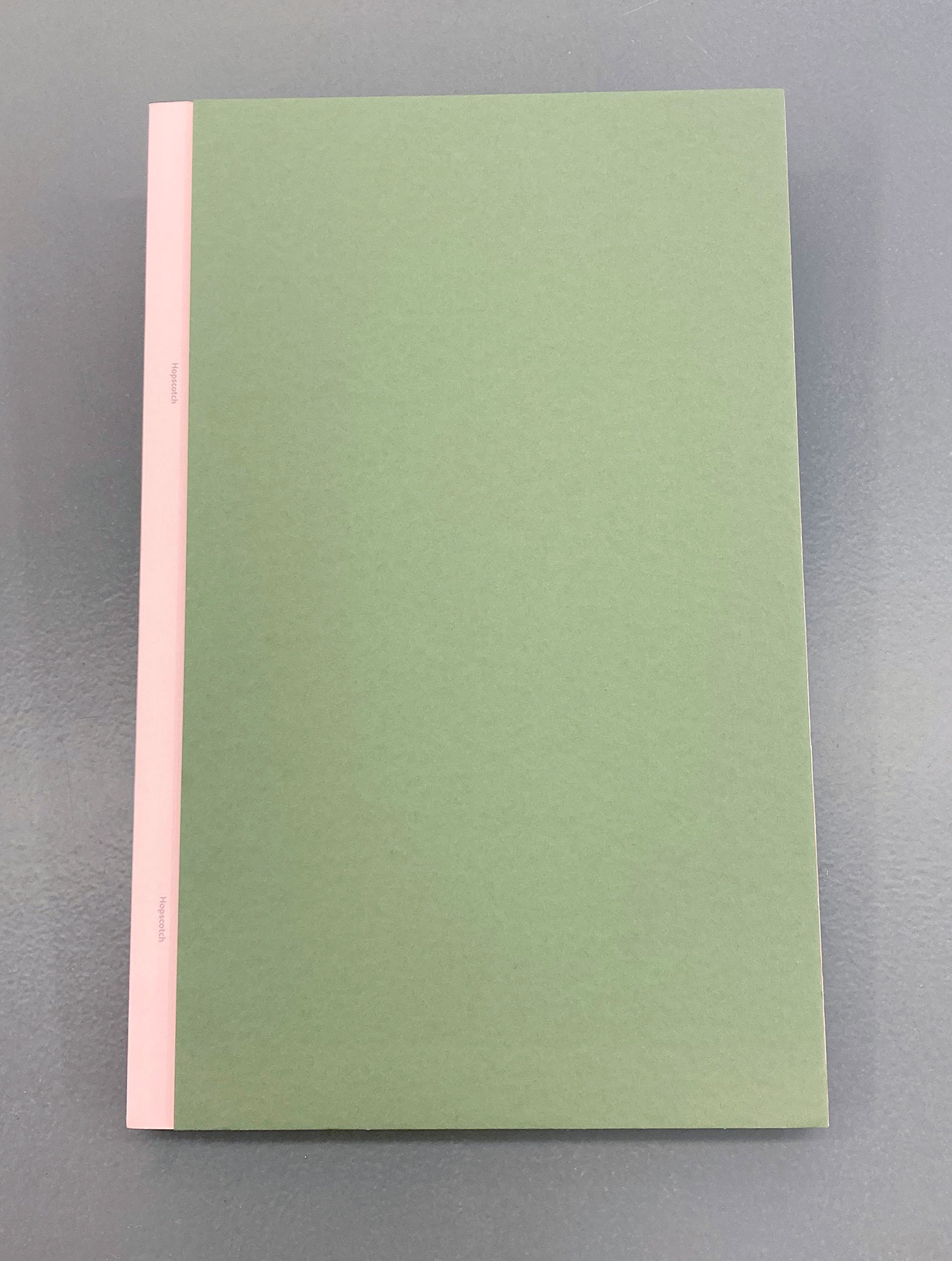

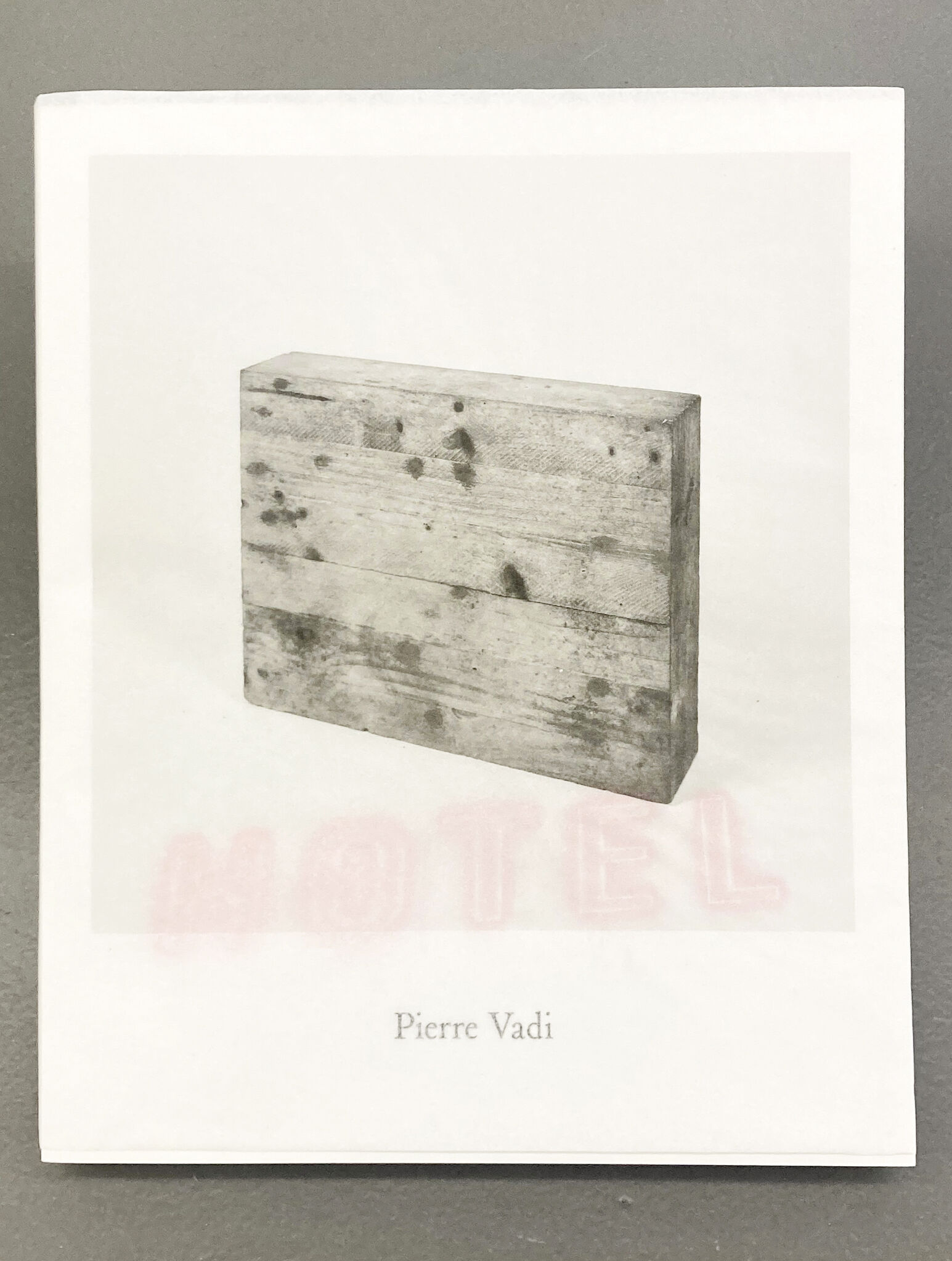

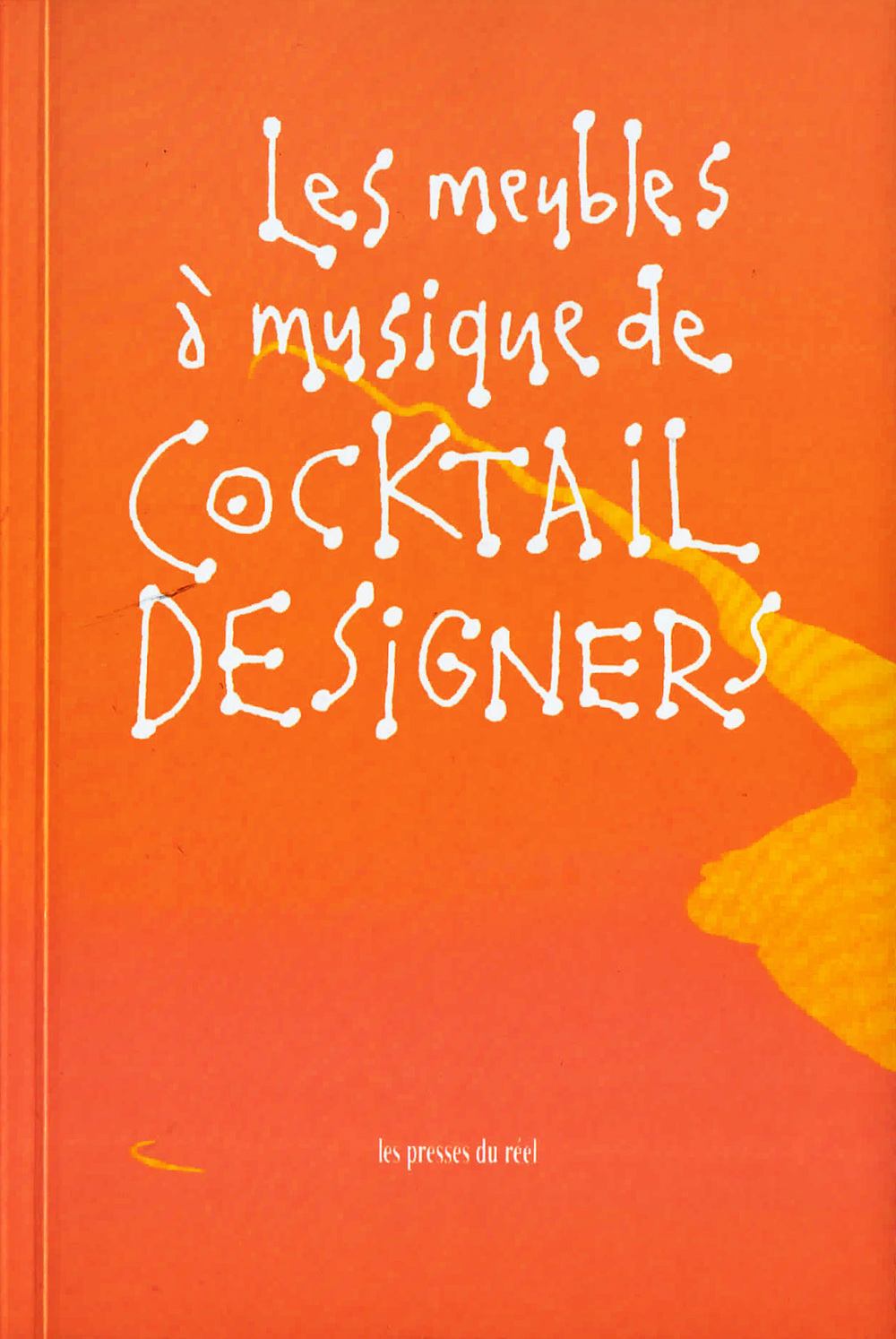

Set of publications, 2015-2022

Donut lamp, 2019/2022

light bulb and donut

Grow the revolution, 2021

poster

12th February to 17th February, 2022

collage

Hanging Light, 2022

light bulb and painting on vinyl

Grow the revolution, 2022

model, mixed media and poster

Iloveyouall, 2022

poster

Badge, 2015

badge

Jolly Good books, 2015-2022

fanzines

Technologies of the self, 2022

painting on canvas

Joni does it with her teeth, 2022

painting on canvas

Hofner ignition violin bass, Star-club, Hamburg 1962, 2022

painting on canvas

Set of recent publications, 2021-2022

fanzines and photocopies

Owen D. Piper (1975, Londres), vit et travaille à Glasgow.

Ses dernières expositions personnelles et collectives regroupent notamment : I’ll be your city, Good press, Glasgow, 2019 ; Elle disait bonjour aux machines, Villa du parc, Annemasse, 2019 ; Mash, avec Cheryl Donegan, Downstairs Projects, New York, 2018 ; How to talk dirty and influence people, avec Lili Reynaud Dewar, SALTS, Birsfelden, Suisse, 2016 ou encore Deep screen, Parc Saint Leger, Pougues Les Eaux, 2015.

Parmi ses publications récentes, citons Images du monde, visite d’atelier, éditions Connoisseurs, 2018 et Le jeu de l’image, avec Charlie Hammond, autoédition, 2019.

Owen D. Piper (1975, London), lives and works in Glasgow.

Recent solo and group exhibitions include: I'll be your city, Good press, Glasgow, 2019; Elle disait bonjour aux machines, Villa du parc, Annemasse, 2019; Mash, with Cheryl Donegan, Downstairs Projects, New York, 2018; How to talk dirty and influence people, with Lili Reynaud Dewar, SALTS, Birsfelden, Switzerland, 2016 or Deep screen, Parc Saint Leger, Pougues Les Eaux, 2015.

His recent publications include Images of the world, studio visit, Connoisseurs Editions, 2018 and The game of the image, with Charlie Hammond, self-publishing, 2019.

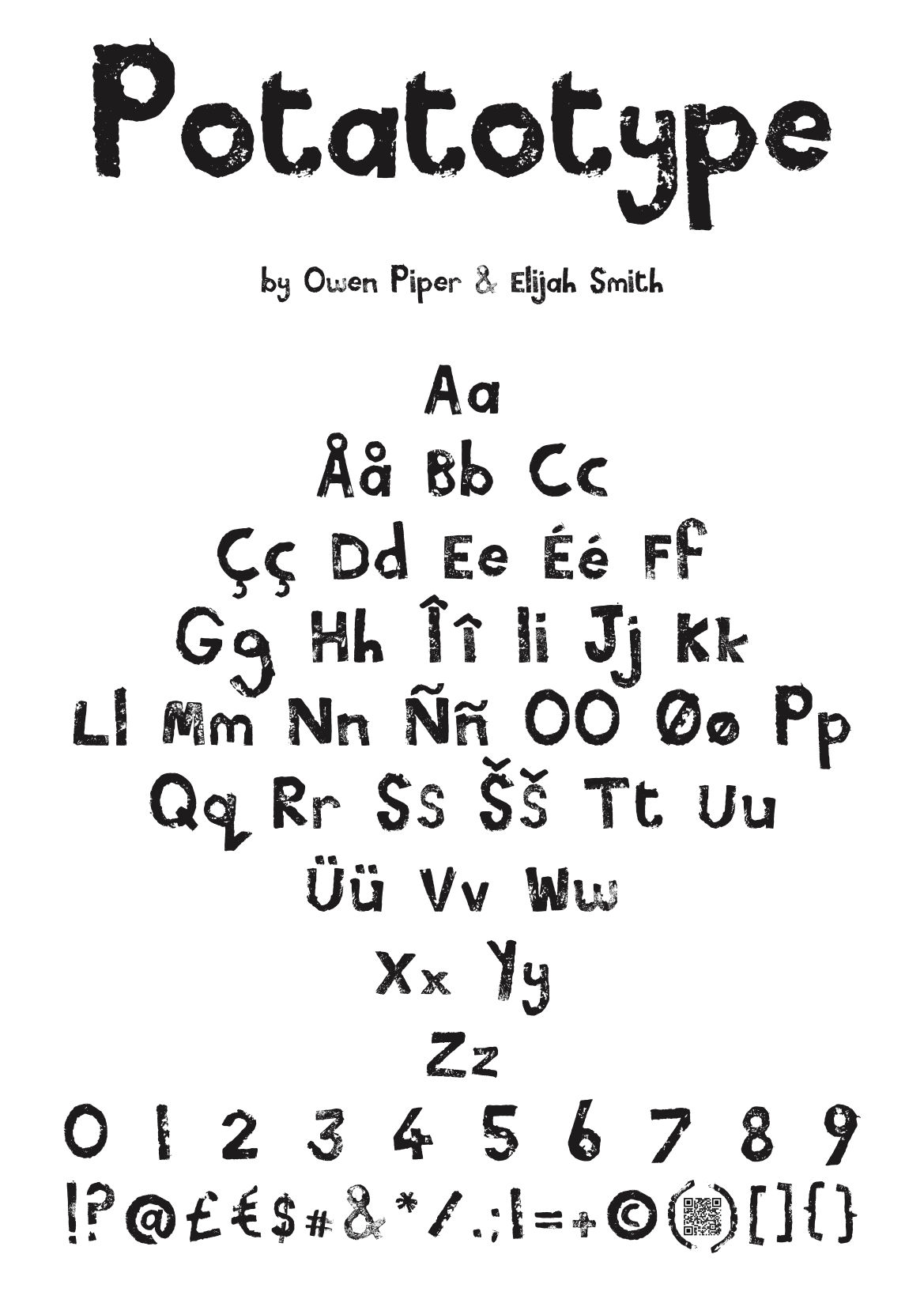

Pendant la durée de l'exposition, les polices de caractère dessinées par Owen Piper et Elijah Smith sont disponibles : Potatotype Regular et Potatotype Filled.

de la Région Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes et de la Ville de Lyon.