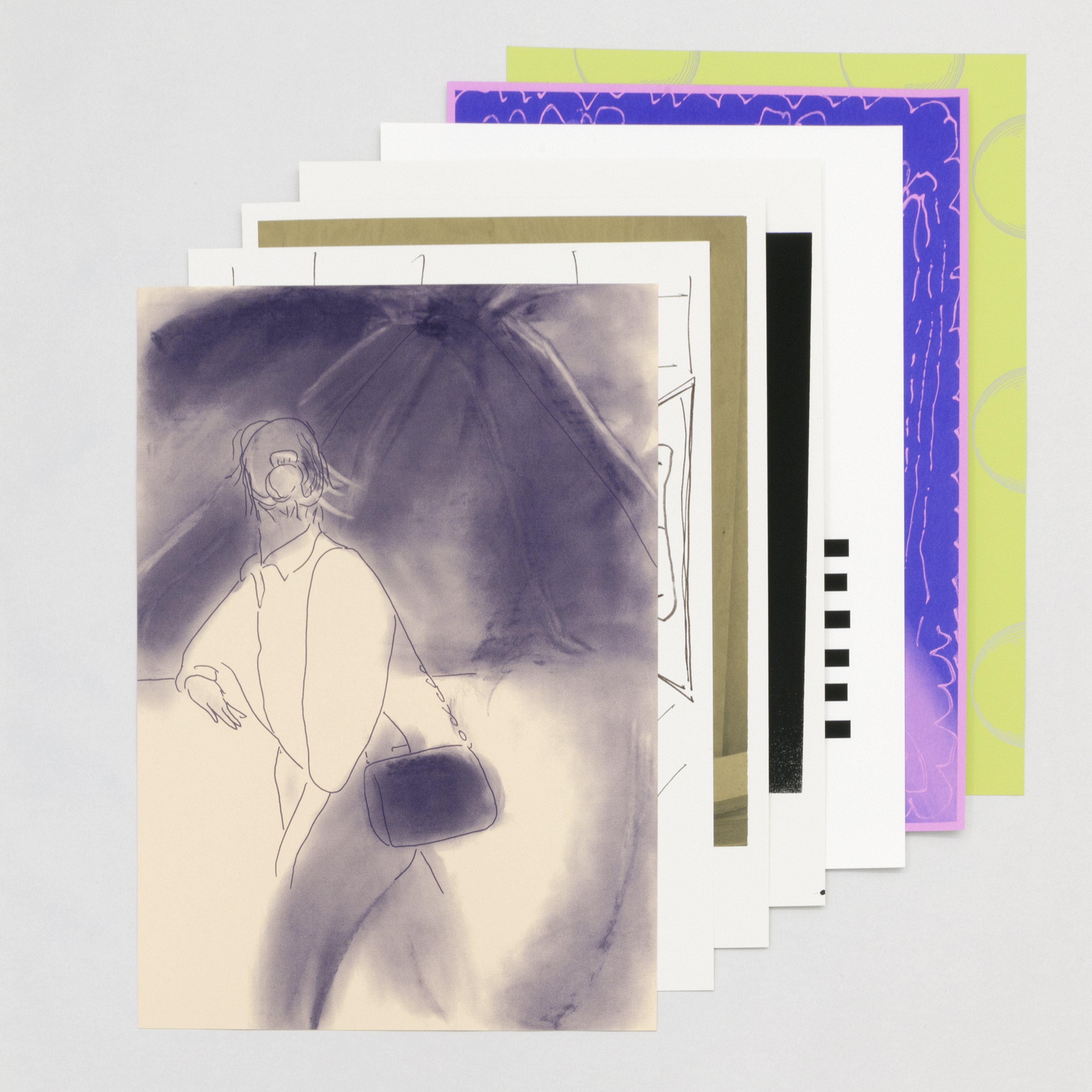

Photos: Mathis Altmann.

Photos: Mathis Altmann.

Individuality – Pasquart (Biel/Bienne, CH)

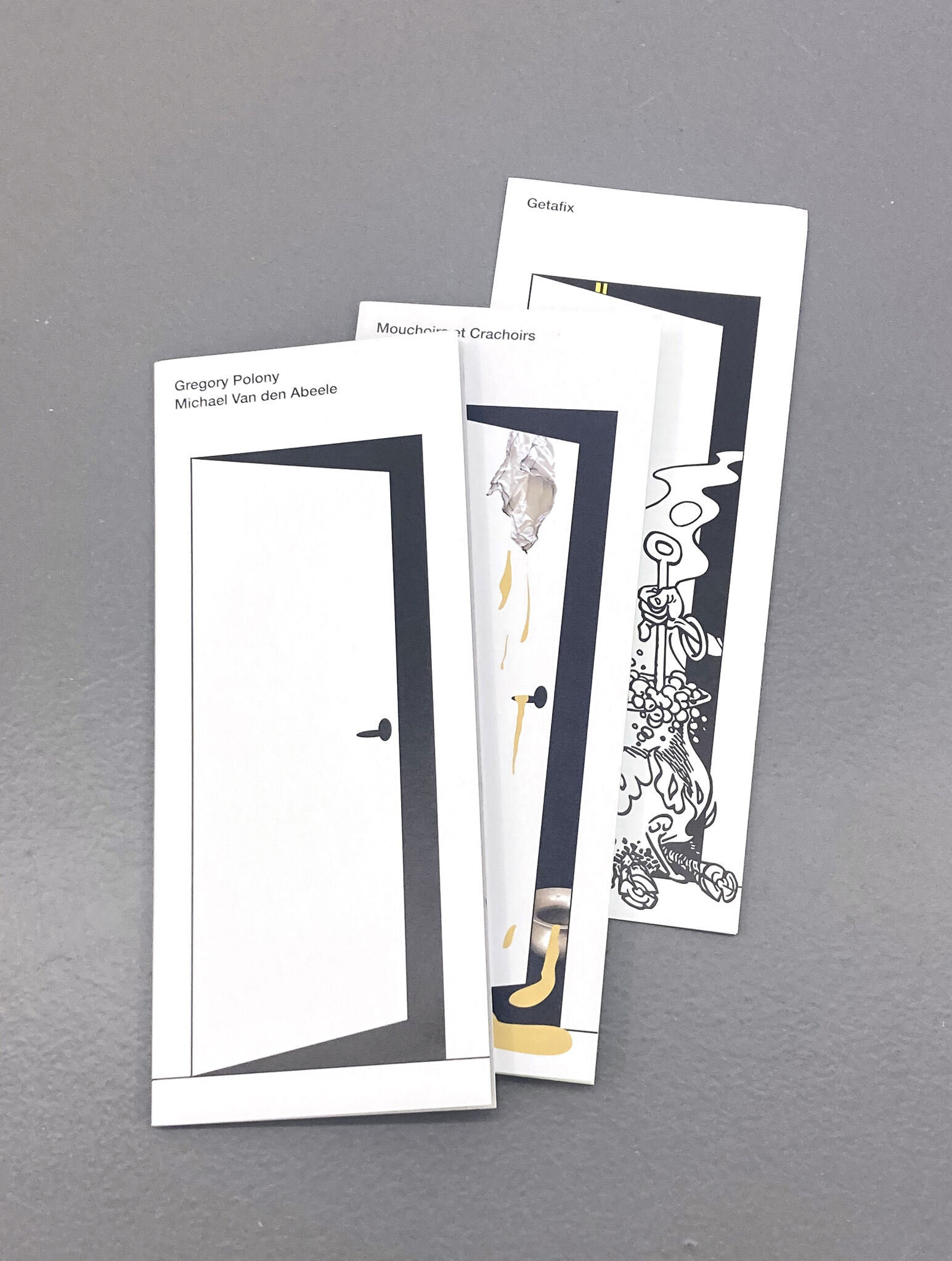

A la suite de l’exposition de Mathis Altmann à la Salle de bains, le Centre d’art Pasquart nous a invités à rejouer le projet de Lyon dans la plus grande salle de l’institution consacrée aux expositions temporaires, la salle Poma.

En parallèle, Pasquart accueillait la première rétrospective de l’artiste français Daniel Pommereule (1937-2003) curatée par Armance Léger.

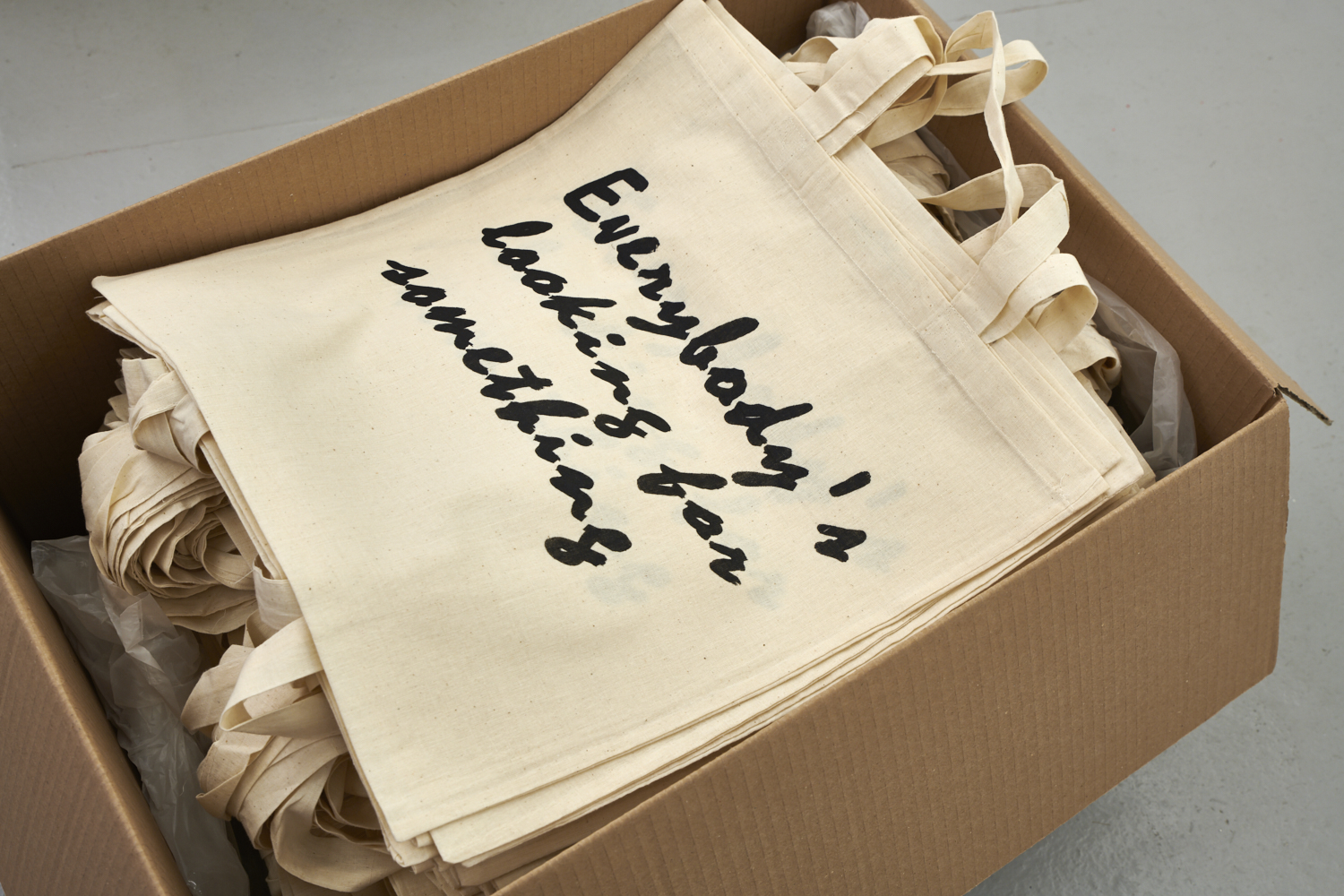

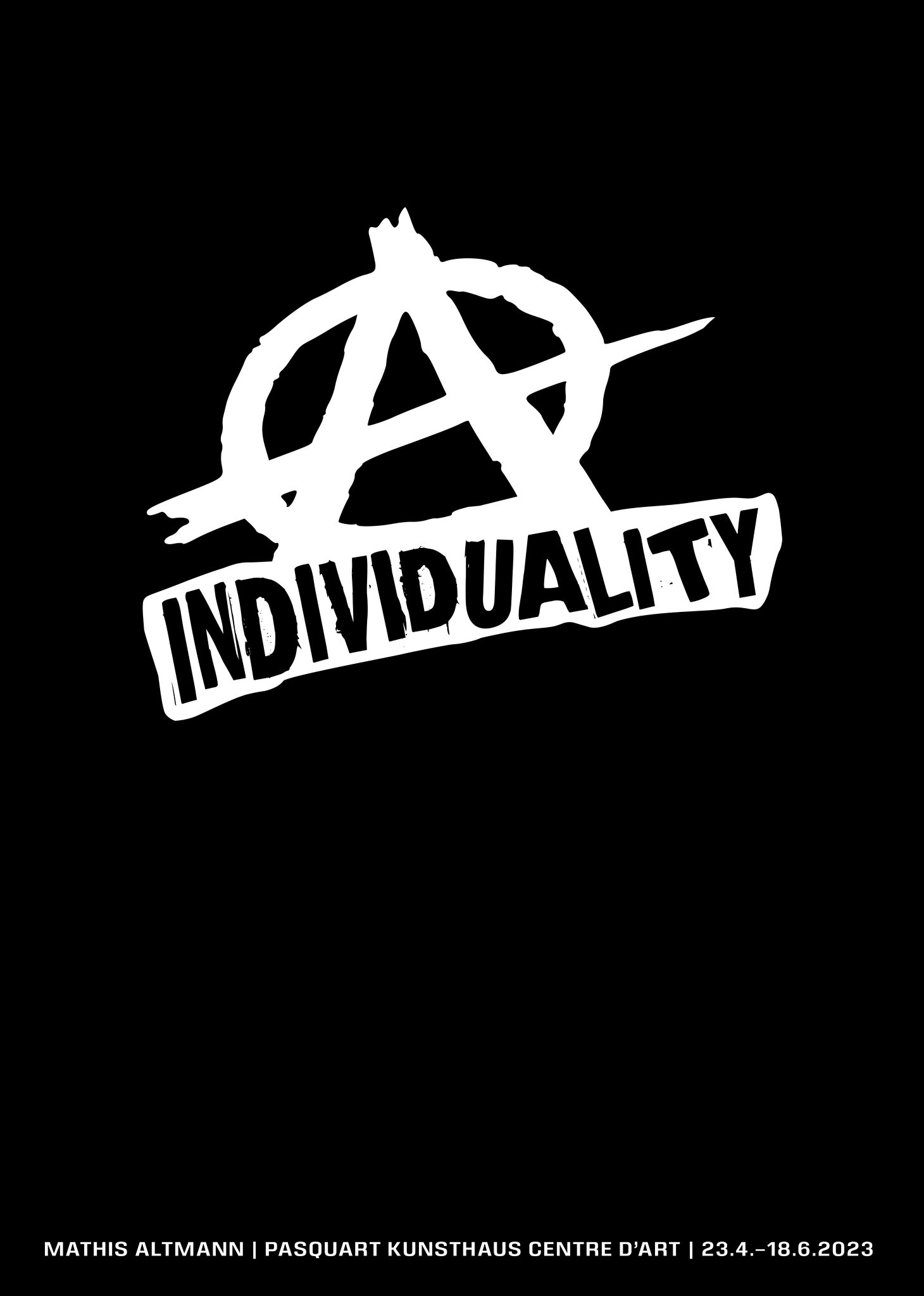

Le titre de l’exposition personnelle de Mathis Altmann dans la monumentale Salle Poma lui a été inspiré par l’image d’un écusson anarchiste circulant sur internet. Le A cerclé y est souligné du mot «INDIVIDUALITY» en lettres capitales dans ce qui apparaît comme une revendication sincère autant que l’emblème tragicomique (et peut-être fait main) de l’état de confusion idéologique laissé par l’absorption des marges dans le modèle ultra-libéral. Mathis Altmann est un fin observateur de ces symptômes dans différents aspects de la culture contemporaine. Il leur porte un regard critique mais aussi amusé, et même tendre, quand ils expriment encore une fidélité aux mouvements de la contre-culture par-delà leurs multiples réappropriations commerciales, ou qu’ils traduisent les aspirations de sa génération à des expériences intenses via des abus de langage, qualifiant toute chose désirable de «hard» et de «core». L’emprunt de ce logo antithétique dans une des œuvres de l’exposition et sa reprise sur l’affiche produite en parallèle de la communication officielle du centre d’art pourrait signer, là aussi, l’affirmation d’une volonté d’indépendance tout en admettant le caractère accessoire de son geste, ce qui revient à une formule poétique plutôt efficace (si vous la cherchez, elle est disponible à l’accueil).

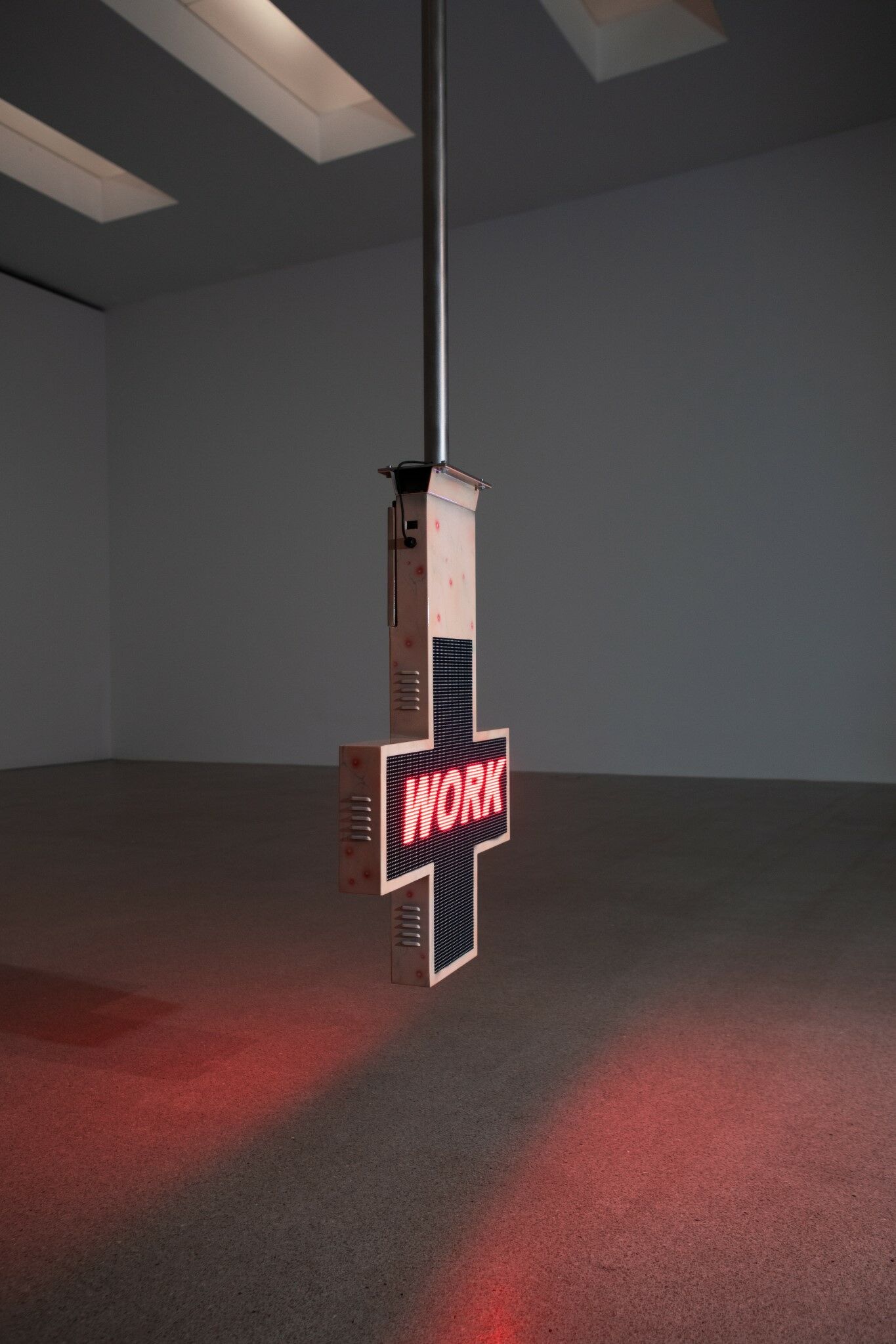

L’artiste qui a grandi dans les années 2000 a pris acte de la neutralisation du potentiel subversif de l’underground et de l’art par le capitalisme ayant transformé en valeurs compétitives les instruments de libération qu’étaient l’autogestion, la créativité ou la réalisation de soi (de son «individualité»). Comment envisager, dès lors, l’élaboration d’une esthétique capable de contrer l’esthétisation de l’économie post-industrielle, d’assumer une fonction critique qui ne soit déjà cannibalisée? La question n’est pas directement posée dans le travail de Mathis Altmann, bien qu’il semble proposer différentes options dans lesquelles il s’engage avec force et même une certaine exagération – où l’on présumera une certaine ironie. Est exclue, en revanche, la stratégie de l’improductivité réclamée périodiquement dans l’art en s’en remettant quasi-religieusement à des figures révolutionnaires tel Guy Debord, qui commit en 1953, à Paris, son célèbre graffiti «NE TRAVAILLEZ JAMAIS», ou à des postures d’oisiveté radicale comme celle qu’incarne le personnage joué par Daniel Pommereulle dans La Collectionneuse d’Éric Rohmer (1967), s’appliquant à la tâche difficile de ne rien faire. En contre-point, Altmann s’intéresse au syndrome d’hyperactivité professionnelle – et son aggravation dans notre époque post-pandémie. Elle touche une génération d’actif·ve·s – y compris de travailleur·euse·s de l’art – converti·e·s à la méritocratie et complices de leur aliénation par un métier qu’il·elle·s ont eux·elles-même créé. L’artiste relie ce phénomène au pharmakon, symbole ambivalent qui désigne à la fois le poison et le remède, à l’heure où la source du problème prodigue aussi les solutions, si l’on pense aux opérations managériales de «bien-être au travail». Aussi la croix de pharmacie suspendue la tête en bas au centre de la Salle Poma, tel un corps supplicié et malade, diffuse-t-elle une sorte de sermon en images animées sur le thème de la dévotion au travail. Il aurait pu être généré par une intelligence artificielle nourrie par un flux Linkedln de cadres supérieurs et hacké par un groupe sataniste, mais il n’en est rien. Tous les énoncés qui interviennent dans le travail de Mathis Altmann sont puisés dans le flux des discours médiatiques et publicitaires parmi ceux employés à créer de nouveaux besoins chez les consommateur·ice·s ou encore à promouvoir des campagnes de rénovations urbaines assorties à de nouveaux life-styles. C’est l’une des voies critiques empruntées par l’œuvre d’Altmann, soit la réappropriation de motifs préalablement appropriés par le capital (ce qui peut être un jeu sans fin). Ainsi de sa série de sculptures lumineuses qui procèdent au détournement de l’enseigne d’une multinationale leader sur le marché des «solutions d’espaces de travail flexible» dont la marque convoque l’imaginaire des organisations communautaires dans une déclaration sibylline: «we work». On la retrouve au sommet d’immeubles de bureaux vitrés qui prolifèrent avec des équipements de sport et de loisirs culturels à destination des classes supérieures et à la place des friches industrielles qui étaient jusqu’alors d’autres types d’espaces de liberté.

C’est à l’accélération vertigineuse de ce genre de transformation urbaine qu’assiste Mathis Altmann depuis quelques années à Berlin où il a un atelier. À partir de là, l’agencement des œuvres dans la Salle Poma peut nous apparaître comme une schématisation de l’évolution de la ville, dans une version qui confine volontairement à l’attraction foraine. Notons aussi la manière dont elles se jouent des dimensions spectaculaires du white cube – une nouvelle fois plongé dans l’obscurité – par la miniaturisation ou l’allongement outrancier d’un dispositif d’accroche. Il convient ici de rappeler que ces pièces ont été initialement montrées à la Salle de bains à Lyon, un petit lieu d’art associatif – donc précaire, dans une ville où l’immobilier est lui aussi sous tension, dans un pays où les travailleur·eus·e·s descendent chaque semaine dans la rue…

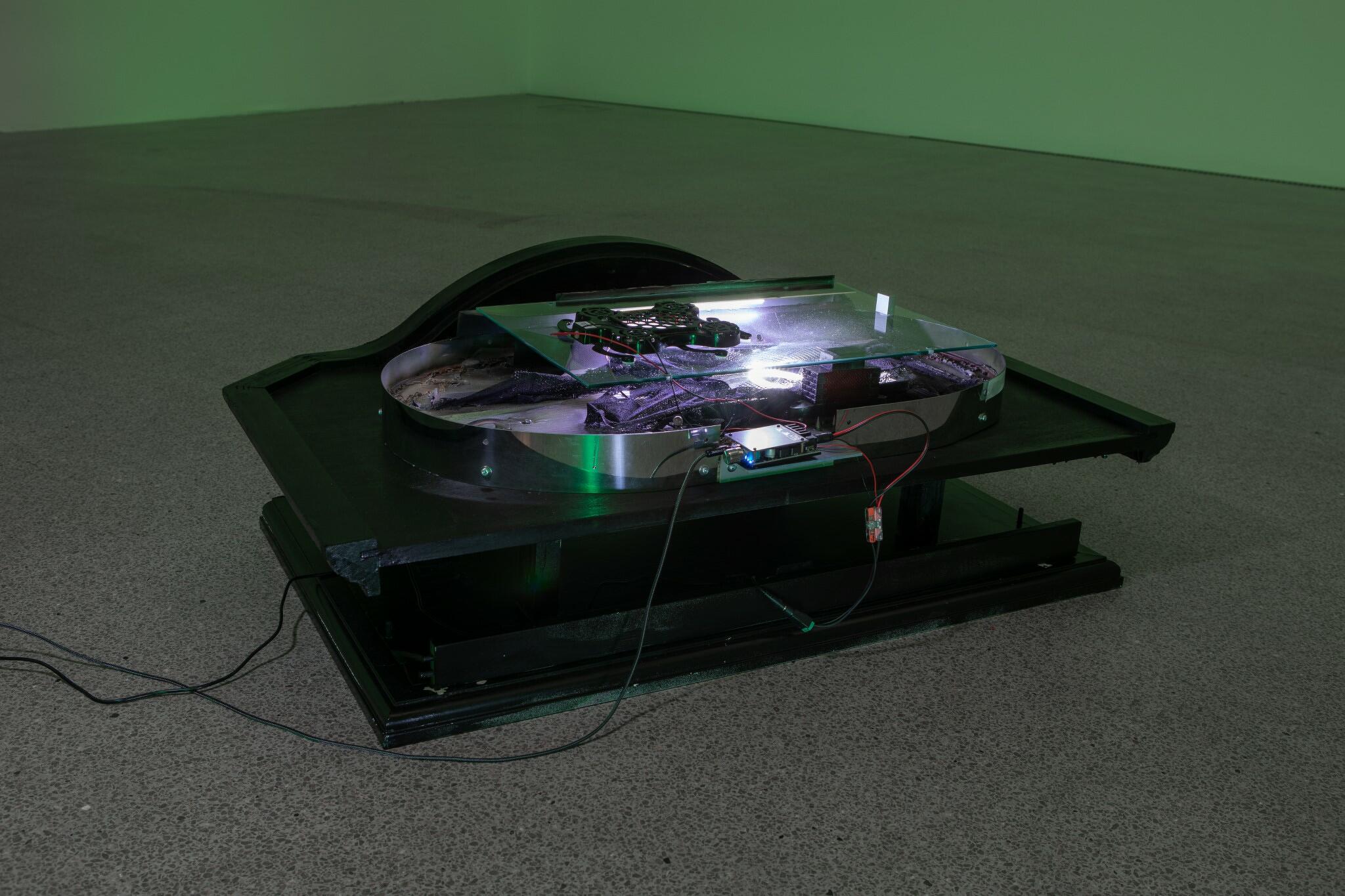

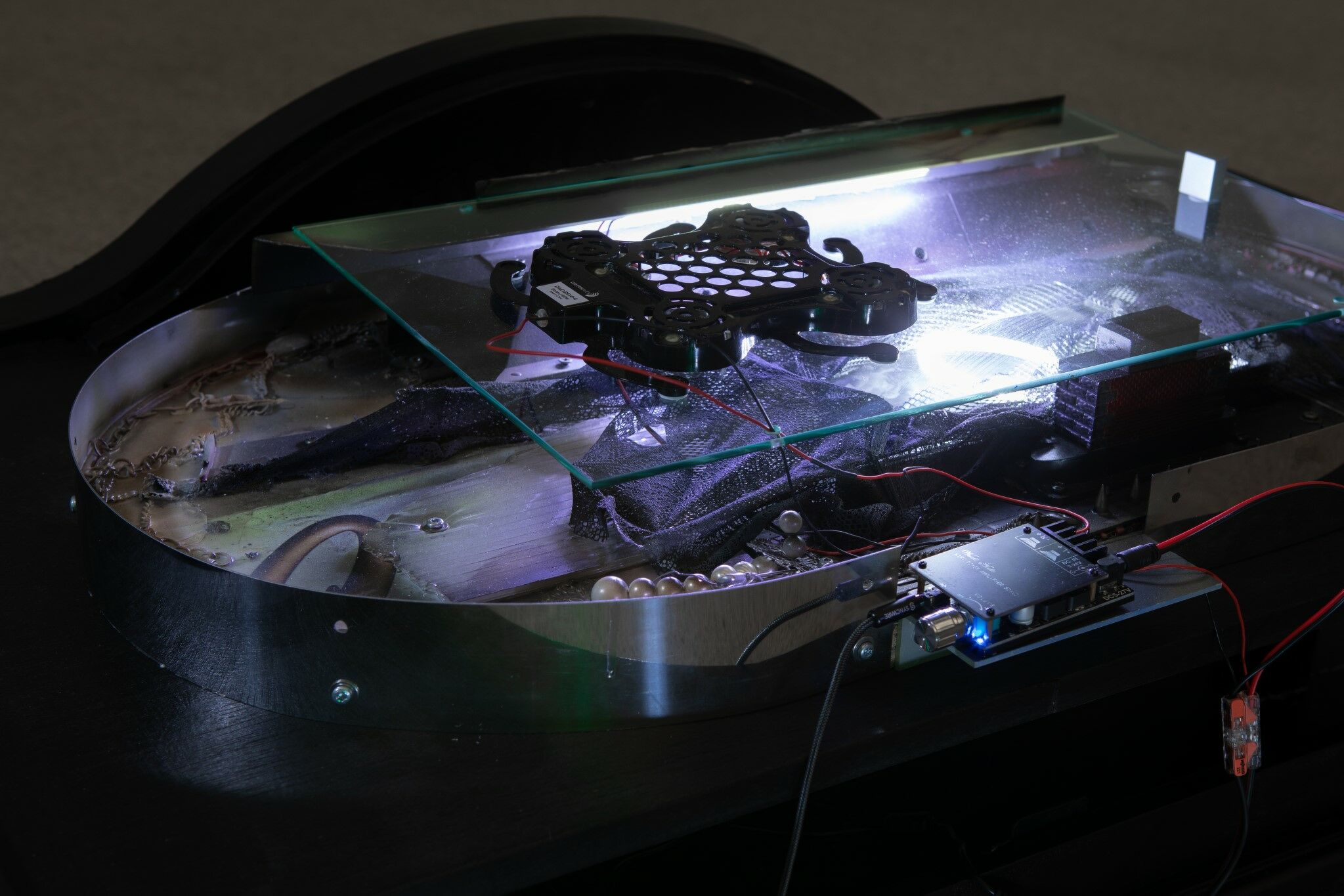

Mais revenons à la Salle Poma: tandis qu’au centre, la croix tourne sur elle-même en offrant le spectacle hypnotique d’une névrose collective bientôt érigée en système productif, à la périphérie, les sculptures sonores qui pourraient évoquer un ensemble de maquettes d’usines désaffectées tantôt converties en night clubs, forment un manège ou une machine en rodage. Ces œuvres procèdent par assemblage – une autre stratégie critique qui compte un fort héritage dans l’histoire de l’art – dont la ville fournit le matériau au sens propre, en rejetant dans la rue un flot de débris au rythme de la gentrification systématique de ses quartiers. Elles sont augmentées par un appareillage de technologies récentes qui les met sous tension. L’œuvre procède d’un mouvement organique et cyclique (propre au remix) qui va dans le sens inverse de l’expansion de la «ville générique» décrite par Rem Koolhaas comme un principe «amnésique», consistant à remplacer tout ce qui ne répond plus aux nécessités et aux goûts présents. C’est le refoulé rugueux et ardent de ce réel uniformisé que nous livre l’œuvre de Mathis Altmann.

Julie Portier

Following Mathis Altmann's exhibition at the Salle de bains, the Centre d'art Pasquart invited us to replay the Lyon project in the institution's largest room devoted to temporary exhibitions, the Salle Poma.

At the same time, Pasquart hosted the first retrospective of French artist Daniel Pommereule (1937-2003), curated by Armance Léger.

The title of Mathis Altmann’s solo exhibition in the monumental Poma Room was inspired by an image of an anarchist emblem circulating on the internet. The circled A is underscored by the word «INDIVIDUALITY» in capital letters, appearing as both a sincere claim and a tragicomic emblem (possibly handmade) representing the ideological confusion resulting from the absorption of margins into the ultra-liberal model. Altmann keenly observes these symptoms across various aspects of contemporary culture. He approaches them critically yet also with amusement and even tenderness when they express fidelity to countercultural movements beyond their multiple commercial reappropriations or when they reflect his generation’s aspirations for intense experiences through language abuses, labelling everything desirable as «hard» and «core.» The adoption of this antithetical logo in one of the exhibition’s works and its inclusion in the simultaneously produced poster for the art centre’s official communication could also signify the affirmation of a desire for independence while acknowledging the accessory nature of the gesture, leading to a rather effective poetic formula (if you seek it, it’s available at the reception).

Having grown up in the 2000s, the artist acknowledges the neutralisation of the subversive potential of the underground andartbycapitalism, whichhasturnedinstrumentsofliberation such as self-management, creativity, or self-realisation («individuality») into competitive values. Consequently, how can the development of an aesthetic capable of countering the aestheticisation of the post-industrial economy be envisaged, assuming a critical function not already cannibalised? While Mathis Altmann’s work doesn’t directly pose this question, it seems to propose various options in which he engages forcefully and even with a certain exaggeration—presumably with a hint of irony. However, the strategy of periodic unproductivity advocated in art, almost religiously relying on revolutionary figures like Guy Debord, who famously tagged «NE TRAVAILLEZ JAMAIS» (Never Work) in Paris in 1953, or embracing radical idleness as embodied by the character played by Daniel Pommereulle in Eric Rohmer’s «La Collectionneuse» (1967), dedicated to the challenging task of doing nothing, is excluded. Instead, Altmann focuses on the phenomenon of professional hyperactivity - exacerbated in our post-pandemic era. It affects a generation of active individuals - including art workers - converted to meritocracy and complicit in their alienation through a profession they have created. The artist connects this phenomenon to the «pharmakon,» an ambivalent symbol signifying both poison and remedy, at a time when the source of the problem also offers solutions, considering workplace «well-being» managerial operations. Hence, the upside-down pharmacy cross suspended in the centre of the Poma Room, resembling a tortured and sick body, emits a sort of sermon through animated images on the theme of devotion to work. It could have been generated by an AI fed from a LinkedIn stream of top executives and hacked by a satanist group, but it’s not. All statements within Mathis Altmann’s work are drawn from the flow of media and advertising discourses, among those used to create new needs among consumers or promote urban renewal campaigns accompanied by new lifestyles. This is one of the critical paths taken by Altmann’s work, involving the reappropriation of motifs previously co-opted by capital (which could be an endless game). For instance, his series of illuminated sculptures divert the signage of a multinational leader in the market for «flexible workspace solutions,» whose brand evokes the imagery of community organisations in a cryptic declaration: “We work.» This same signage appears atop glass office buildings proliferating with sports and cultural leisure facilities for the upper classes, replacing industrial wastelands that used to be spaces of a different kind of freedom.

Mathis Altmann has been witnessing the dizzying acceleration of such urban transformations for a few years in Berlin, where he has a studio. Consequently, the arrangement of the artworks in the Poma Room might appear as a schematic representation of the city’s evolution, deliberately verging on the fairground attraction. Noticeably, they play with the spectacular dimensions of the white cube - once again plunged into darkness - through either miniaturisation or excessive elongation of a hanging device. It’s important to note that these pieces were initially shown at the Salle de bains in Lyon, a small associative art space - thus precarious - in a city where real estate is also under pressure, in a country where workers take to the streets every week...

But back to the Poma Room: while at the centre, the cross rotates, offering the hypnotic spectacle of a collective neurosis soon to be erected into a productive system, at the periphery, the sound sculptures resembling a collection of models of abandoned factories occasionally transformed into nightclubs, form a carousel or a machine in trial operation. These works operate through assemblage - another critical strategy with a strong heritage in art history - for which the city provides material quite literally, ejecting a stream of debris onto the streets at the pace of systematic gentrification of its neighbourhoods. They are enhanced by an array of recent technologies that put them under tension. The artwork stems from an organic and cyclical movement (typical of remixes) that runs counter to the expansion of the «generic city» described by Rem Koolhaas as an «amnesic» principle, aiming to replace everything that no longer aligns with present needs and tastes. Mathis Altmann’s work delivers the rough and ardent repressed aspects of this standardised reality.

— Julie Portier

Liste des œuvres :

List of works :

enseigne lumineuse LED

Devine Powerstyles, 2023

croix de pharmacie LED, peinture acrylique sur aluminium, boucle vidéo 13'30"

Untitled, 2023

bois, plastique, métal, verre, peinture acrylique, lumière laser, haut-parleur exciter, boucle audio 06'55"

Untitled, 2023

bois, plastique, métal, verre, tissu, perles, chaines, impression photographique, peinture acrylique, LED, haut-parleur exciter, boucle audio 26'09"

Untitled, 2023

bois, plastique, métal, verre, impression photographique, peinture acrylique,

écran LED, haut-parleur exciter, boucle audio 23'21"

Untitled, 2023

bois, plastique, métal, verre, peinture acrylique, LED, haut-parleur exciter,

boucle audio 05'27"

Untitled, 2023

bois, plastique, verre, peinture acrylique, LED, lampe CCFL, haut-parleur exciter, boucle audio 1h34'

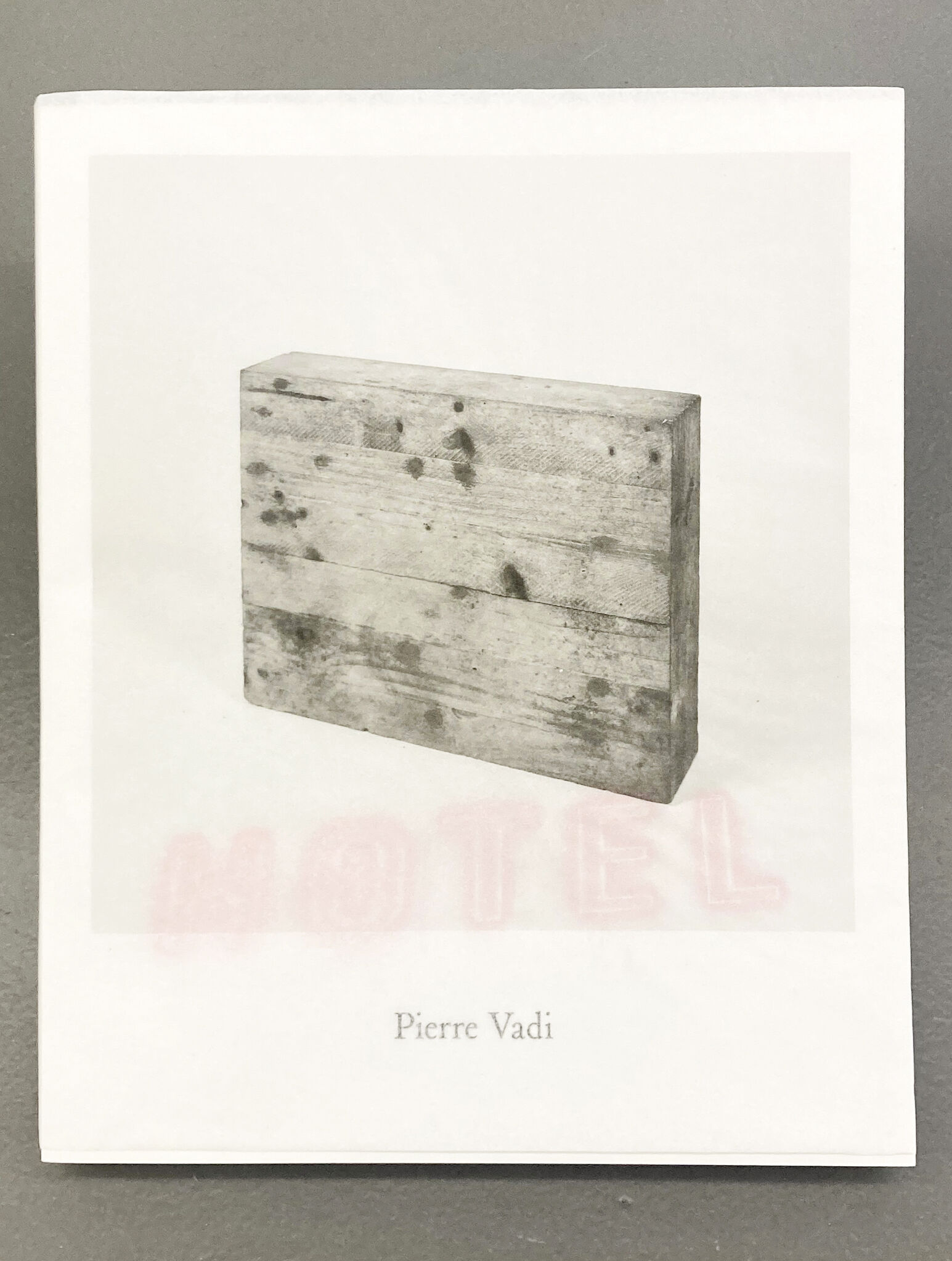

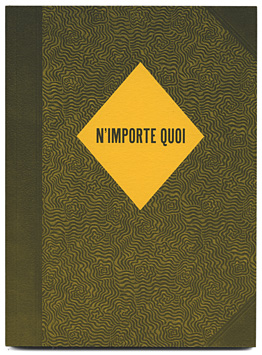

Individuality, 2023

aluminium, peinture aérosol, piercings, chaîne en argent massif, clous, impression photographique, résine, peinture acrylique

LED sign

Devine Powerstyles, 2023

LED pharmacy cross, acrylic paint on aluminium, video loop 13'30"

Untitled, 2023

wood, plastic, metal, glass, acrylic paint, laser light, exciter loudspeaker, audio loop 06'55"

Untitled, 2023

wood, plastic, metal, glass, net, pearl, chains, photo print, acrylic paint, LED, exciter loudspeaker, audio loop 26'09"

Untitled, 2023

wood, plastic, metal, glass, photo print, acrylic paint, LED, exciter loudspeaker, audio loop 23'21"

Untitled, 2023

wood, plastic, metal, acrylic paint, LED, exciter loudspeaker, audio loop 05'27"

Untitled, 2023

wood, plastic, metal, acrylic, glass, LED, CCFL lamp, wood, plastic, metal,acrylic paint, LED 1h34'

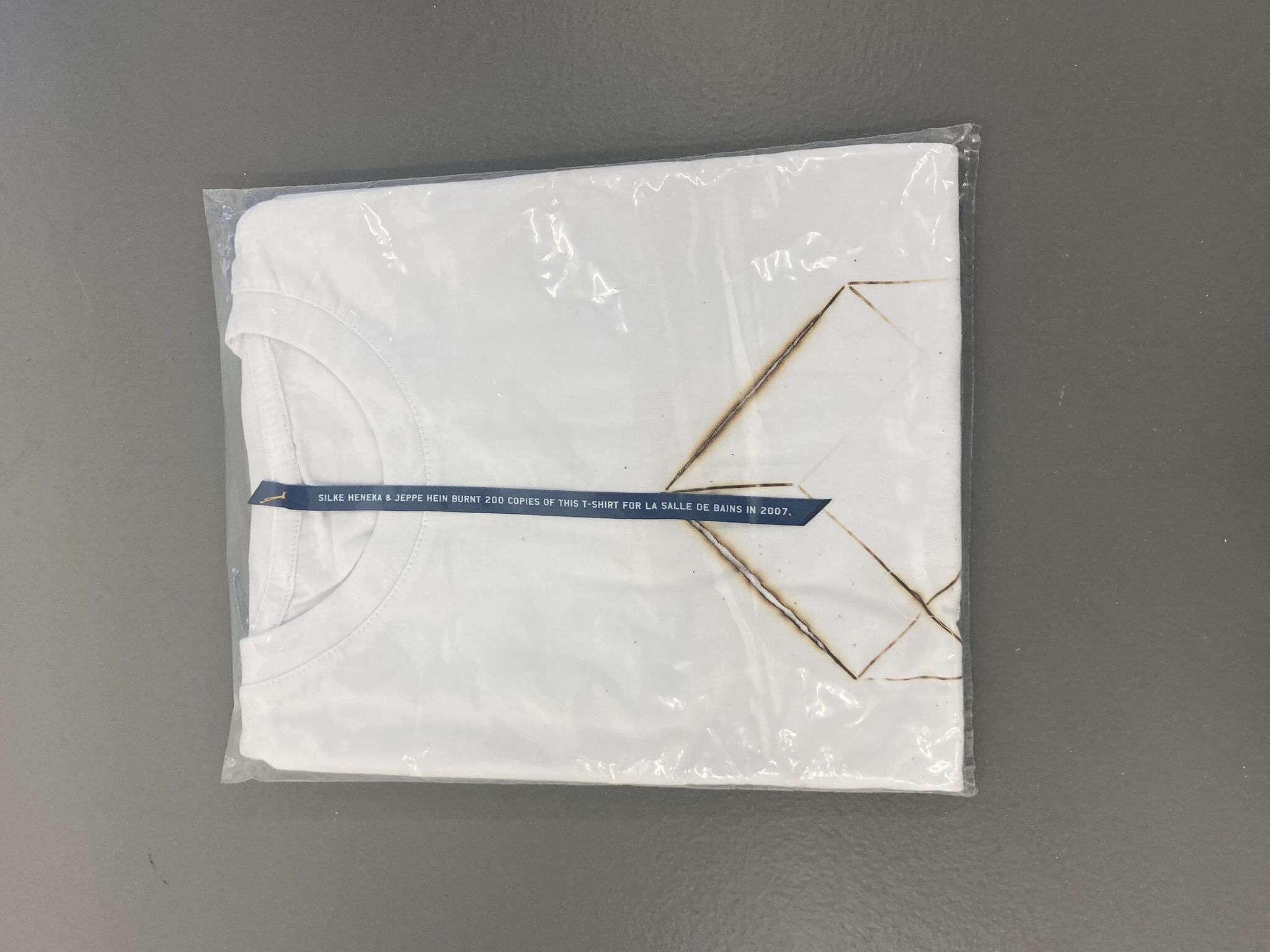

Individuality, 2023

aluminium, spray paint, piercings, silver chain, nails, photographic print , resin, acrylic paint

Son travail a fait l’objet d’expositions monographiques en Allemagne, à Efremidis à Berlin en 2021 ; en Italie, à l’Institut Suisse de Milan en 2018 et en Suisse, au Kunstmuseum de Wintherthur en 2021 et à Truth & Consequences à Genève en 2016. Il a également participé à de nombreuses expositions collectives en 2021 telles que Bijoux ! à Fitzpatrick Gallery à Paris ; Nimmersatt? Imagining Society without Growth au Westfälischer Kunstverein à Münster ; Macht! Licht! au Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, en Allemagne et en 2020 comme Grand Miniature à Zurich ou encore ANNEMARIE VON MATT. JE NE M’ENNUIE JAMAIS, ON M’ENNUIE au Centre Culturel Suisse à Paris.

Il est représenté par Fitzpatrick Gallery à Paris.

His work has been the subject of monographic exhibitions in Germany, at Efremidis in Berlin in 2021; in Italy, at the Swiss Institute in Milan in 2018 and in Switzerland, at the Kunstmuseum in Wintherthur in 2021 and at Truth & Consequences in Geneva in 2016. He has also participated in numerous group exhibitions in 2021 such as Bijoux! at Fitzpatrick Gallery in Paris; Nimmersatt? Imagining Society without Growth at the Westfälischer Kunstverein in Münster; Macht! Licht! at the Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, Germany and in 2020 as Grand Miniature in Zurich or ANNEMARIE VON MATT. JE NE M’ENNUIE JAMAIS, ON M’ENNUIE at the Centre Culturel Suisse in Paris.

He is represented by Fitzpatrick Gallery.

Le commissariat de cette exposition organisée au Centre d'art Pasquart a été mené par Julie Portier, La Salle de bains.