Photos : Jesús Alberto Benítez, Laëtitia Badaut Haussmann.

Photos: Jesús Alberto Benítez

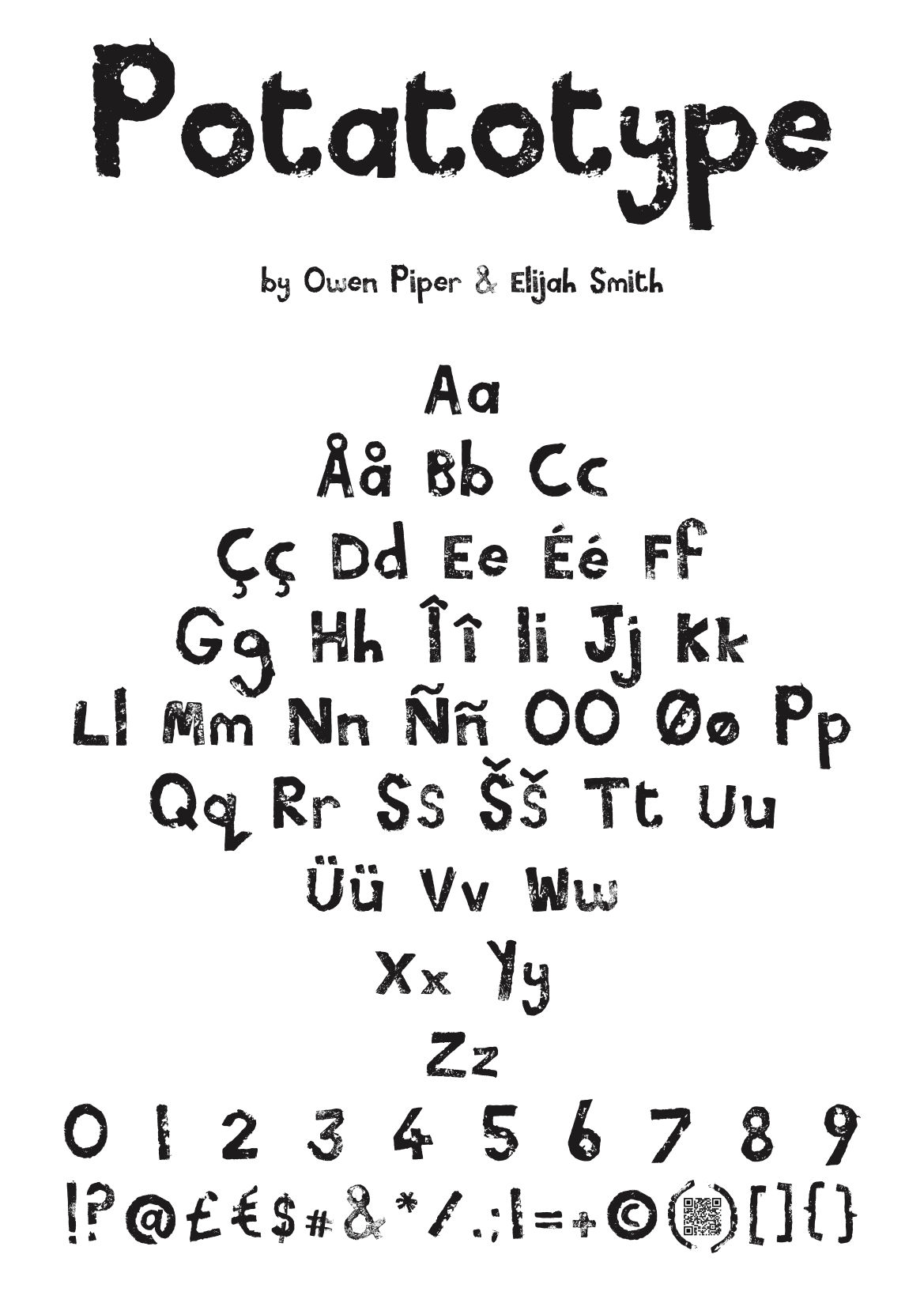

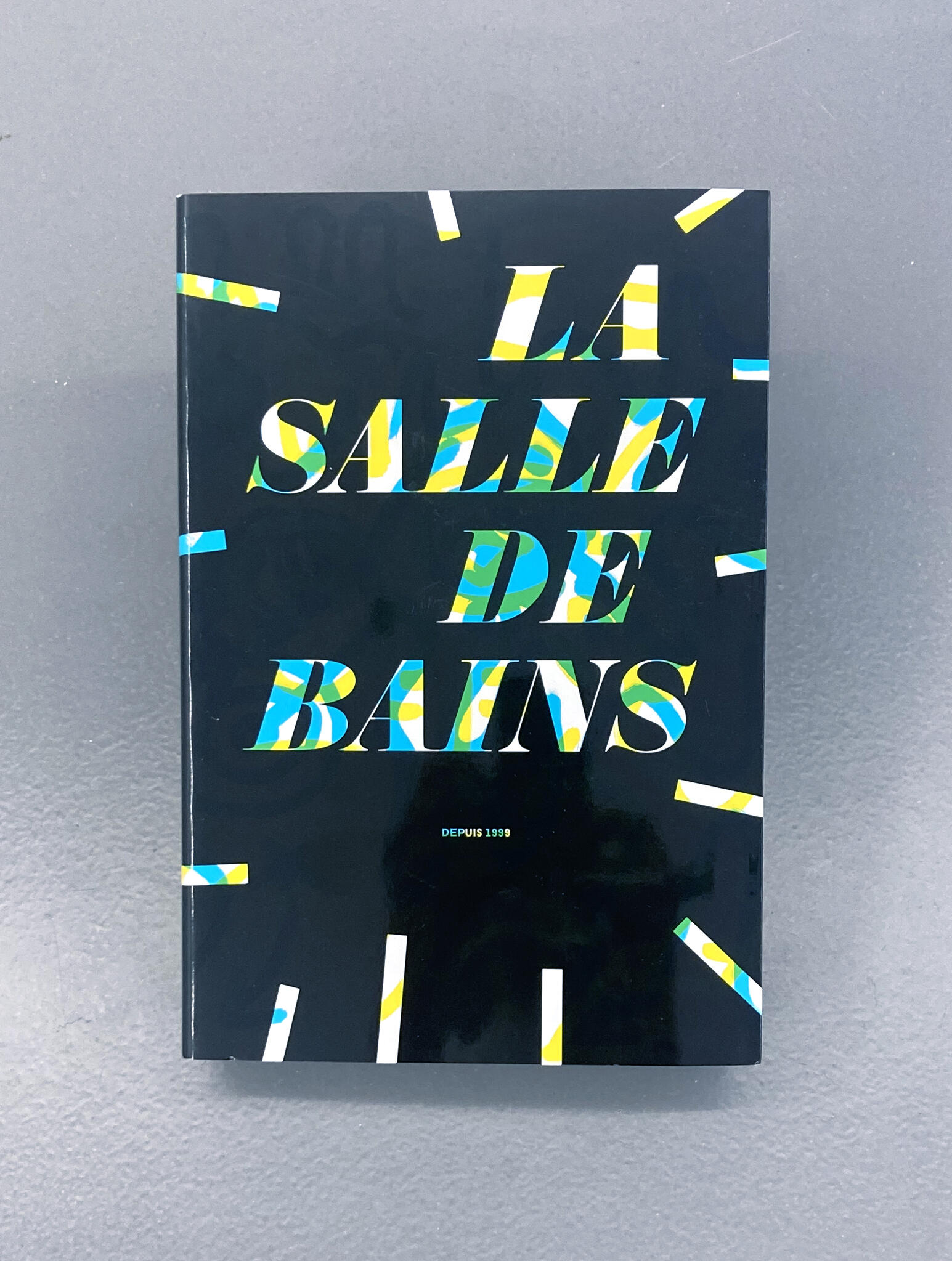

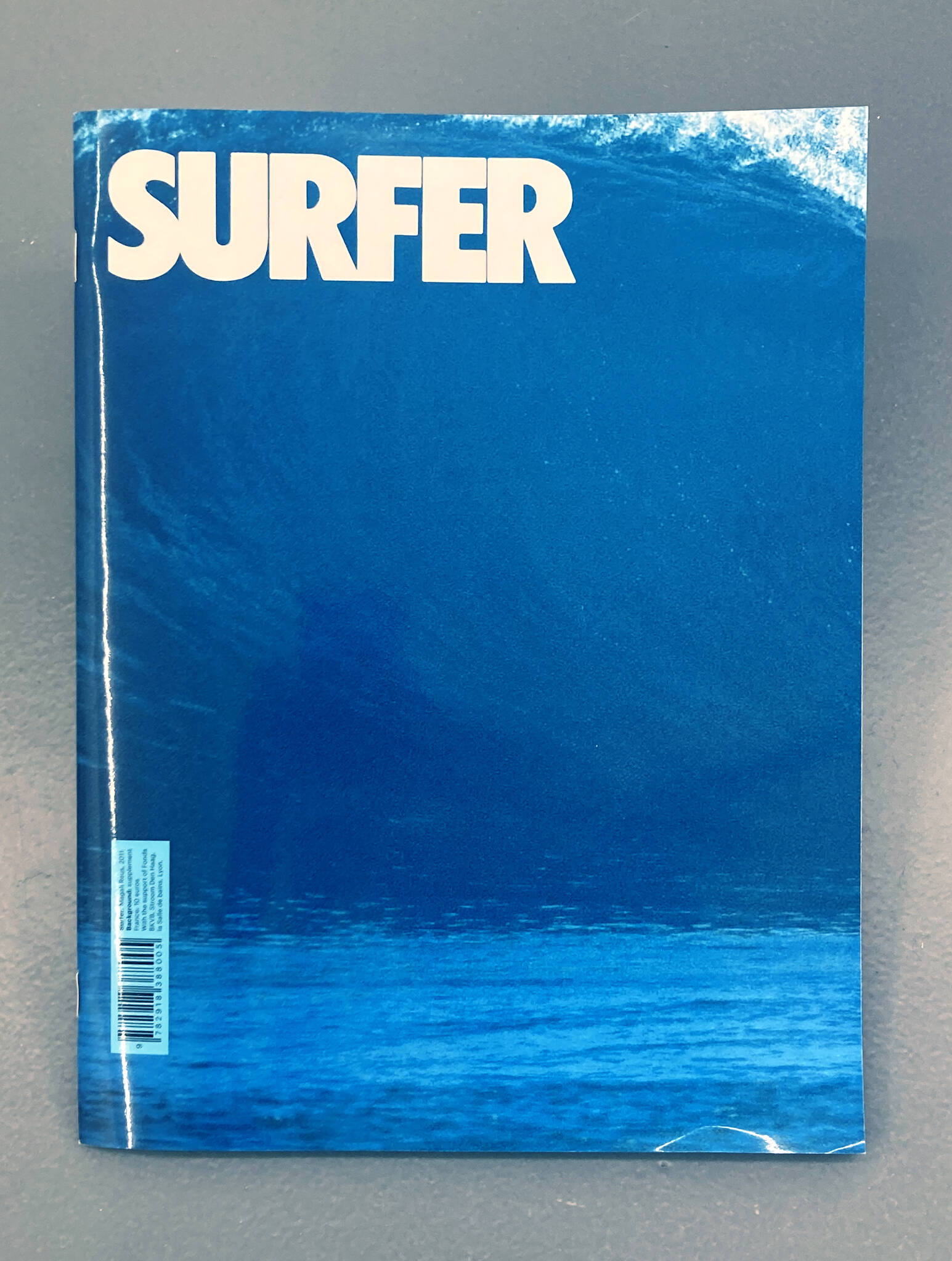

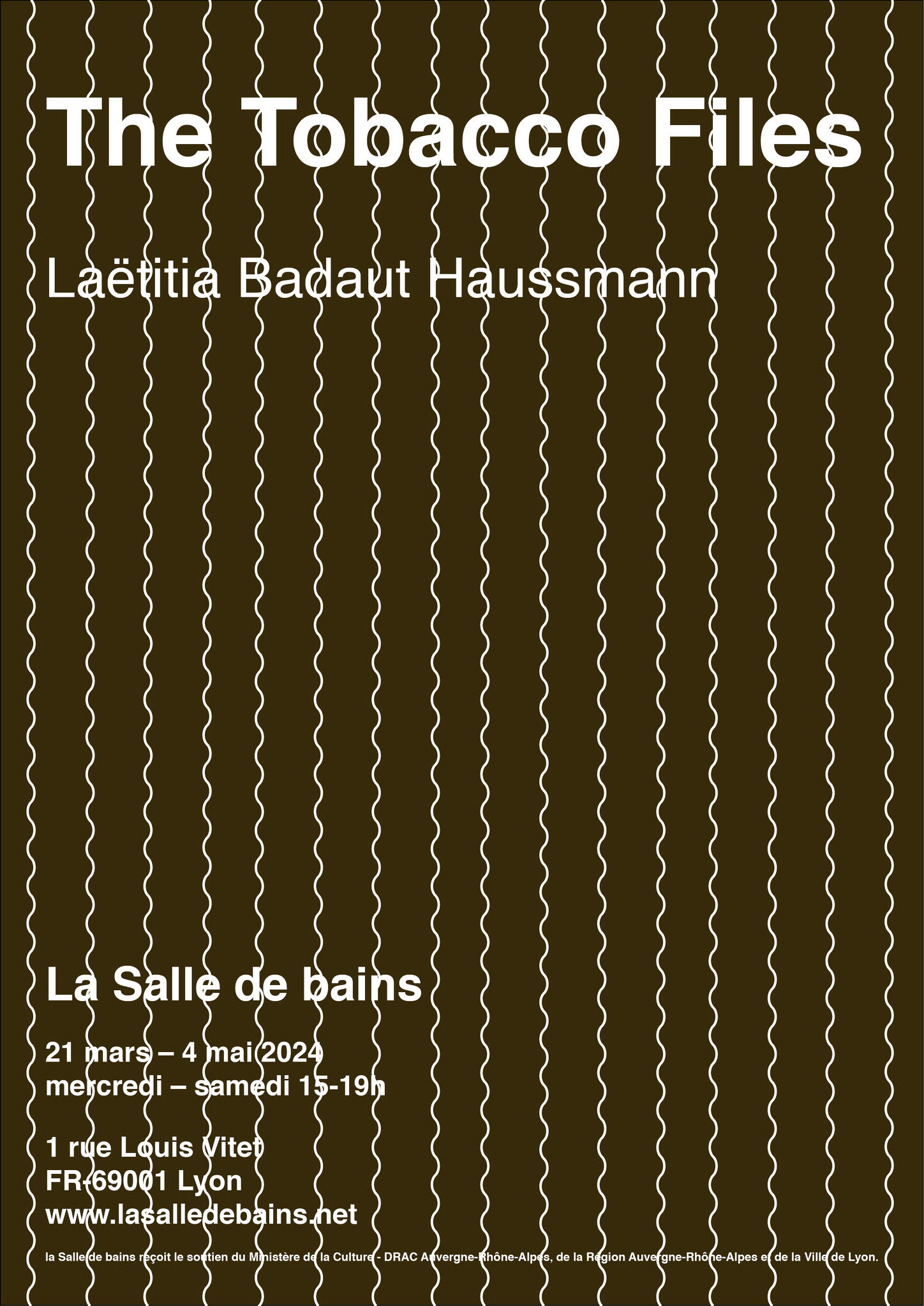

The Tobacco Files

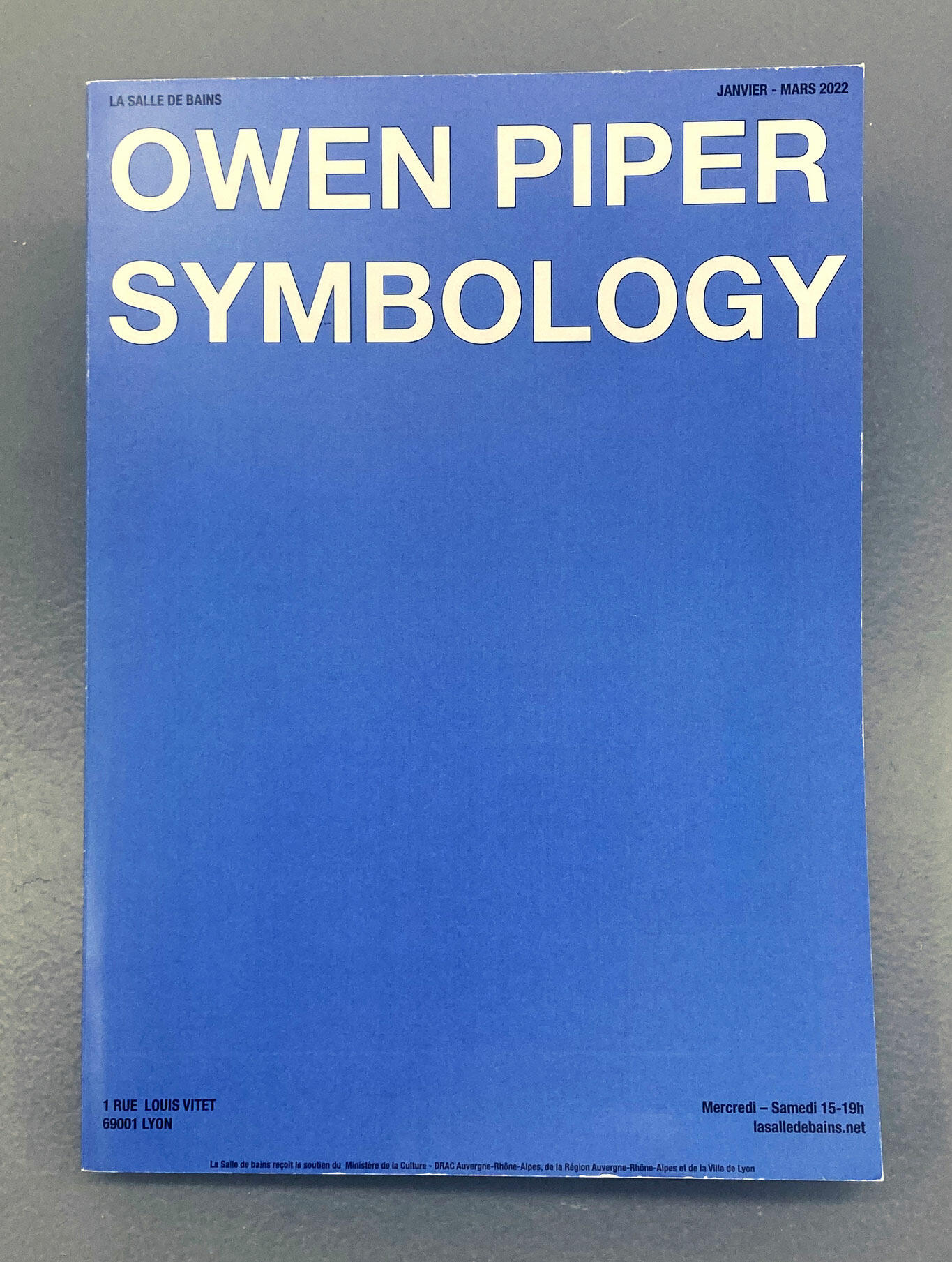

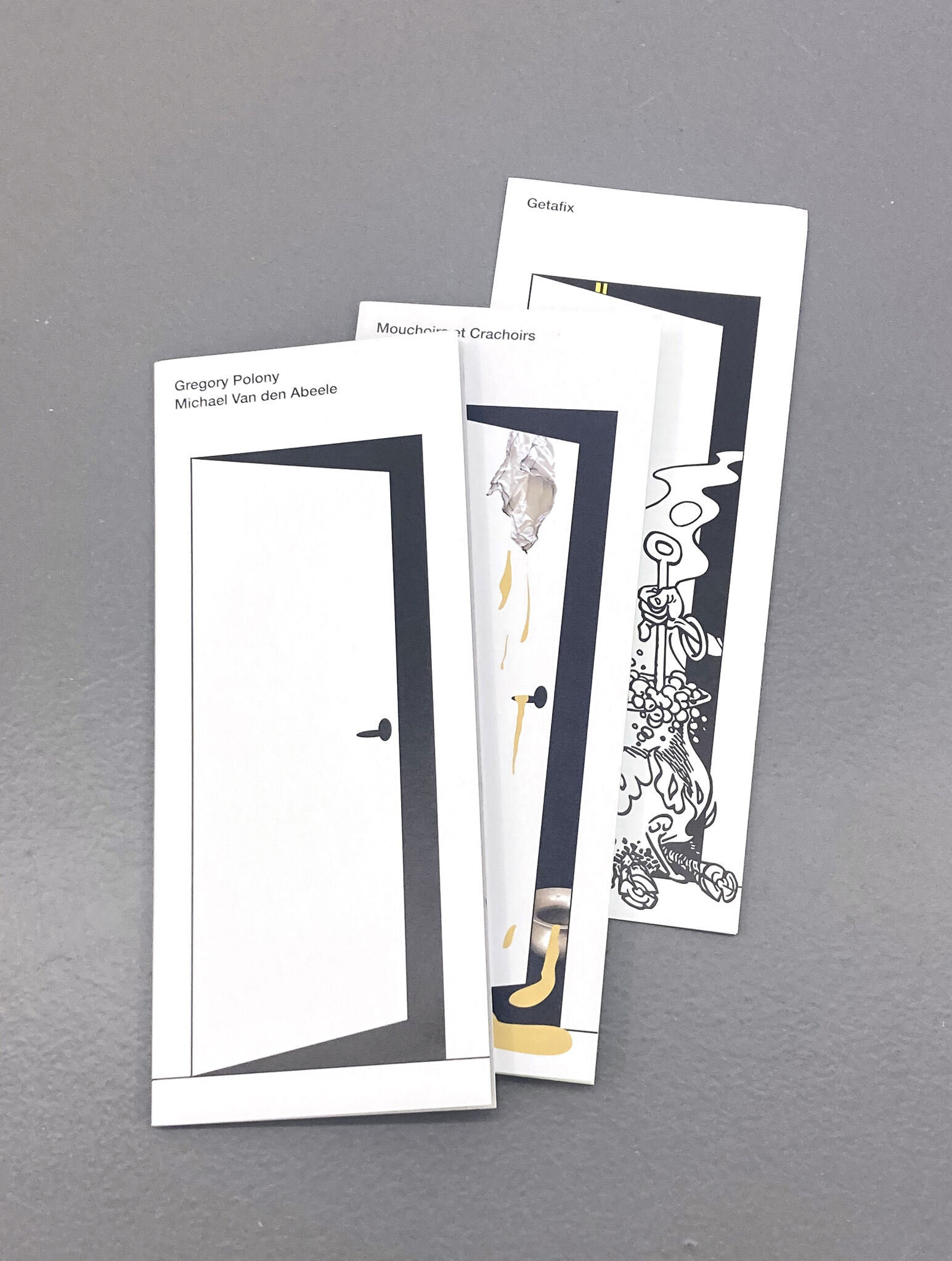

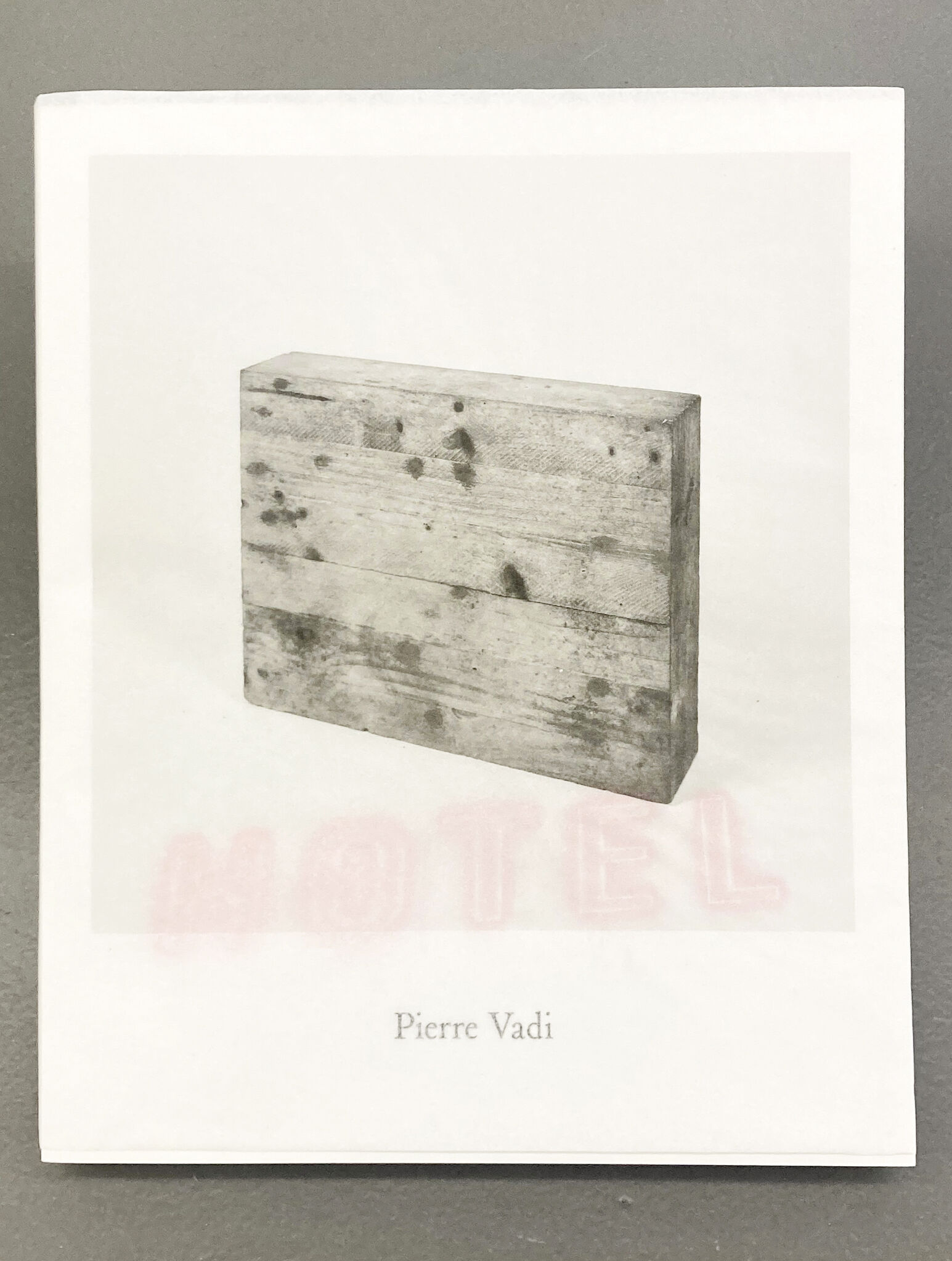

Certain·e·s visiteur·euse·s regrettent l'absence d'une pancarte qui rendrait plus visible la Salle de bains depuis la rue Louis Vitet. Il s'avère que l'association n'a jamais obtenu d'autorisation de ce type. La sculpture installée sur la façade le temps de l'exposition de Laëtitia Badaut Haussmann, elle, est une véritable enseigne de buraliste autrichien achetée sur le marché de seconde main. À Vienne, alors que l’artiste présentait une première étape de ses recherches sur le tabac, cette enseigne avait immédiatement fait l’objet d’un signalement et été décrochée en présence d’un agent assermenté de la compagnie nationale Austria Tabak. De quoi méditer sur l’agentivité du ready-made selon son contexte de présentation mais surtout sur l’autorité de certains signes, même quand ils sont usagés, et la manière dont ils régissent l’espace public, jusque dans la cour d’un espace d’art associatif.

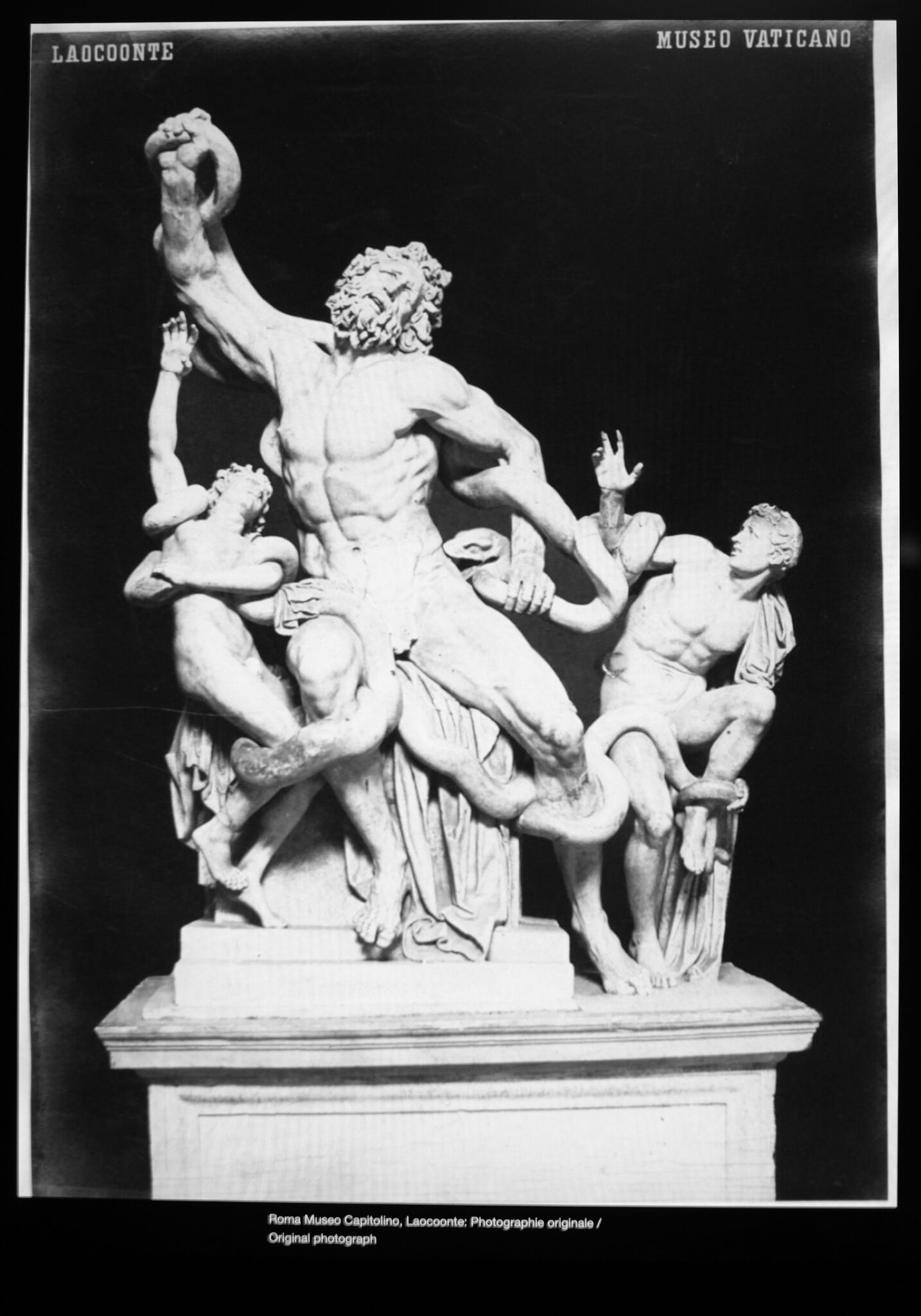

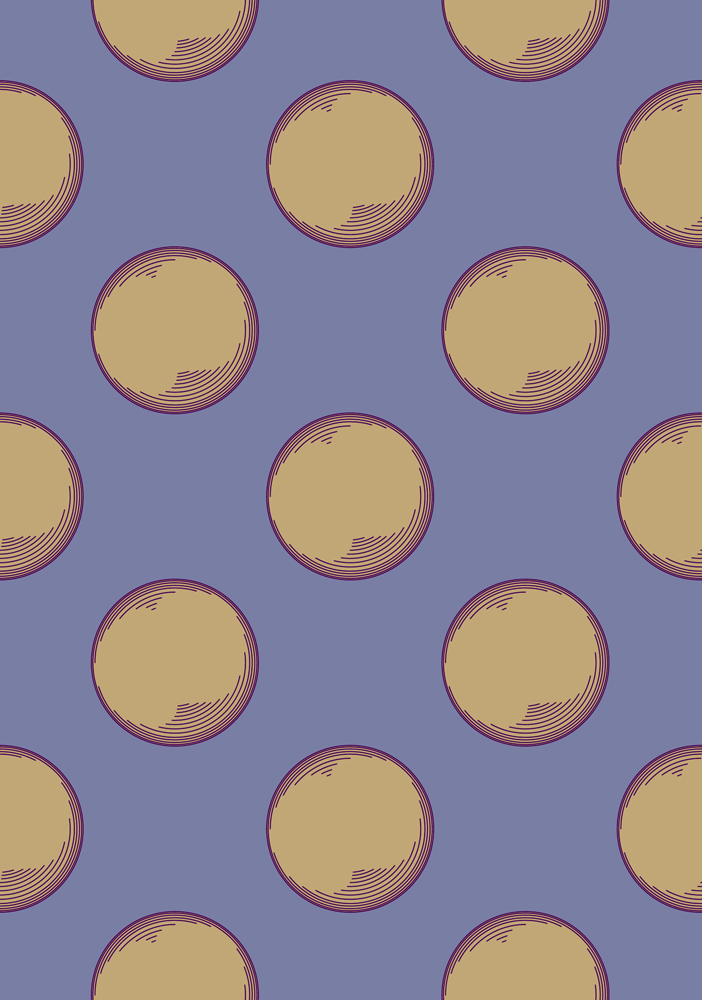

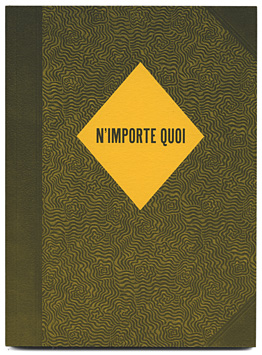

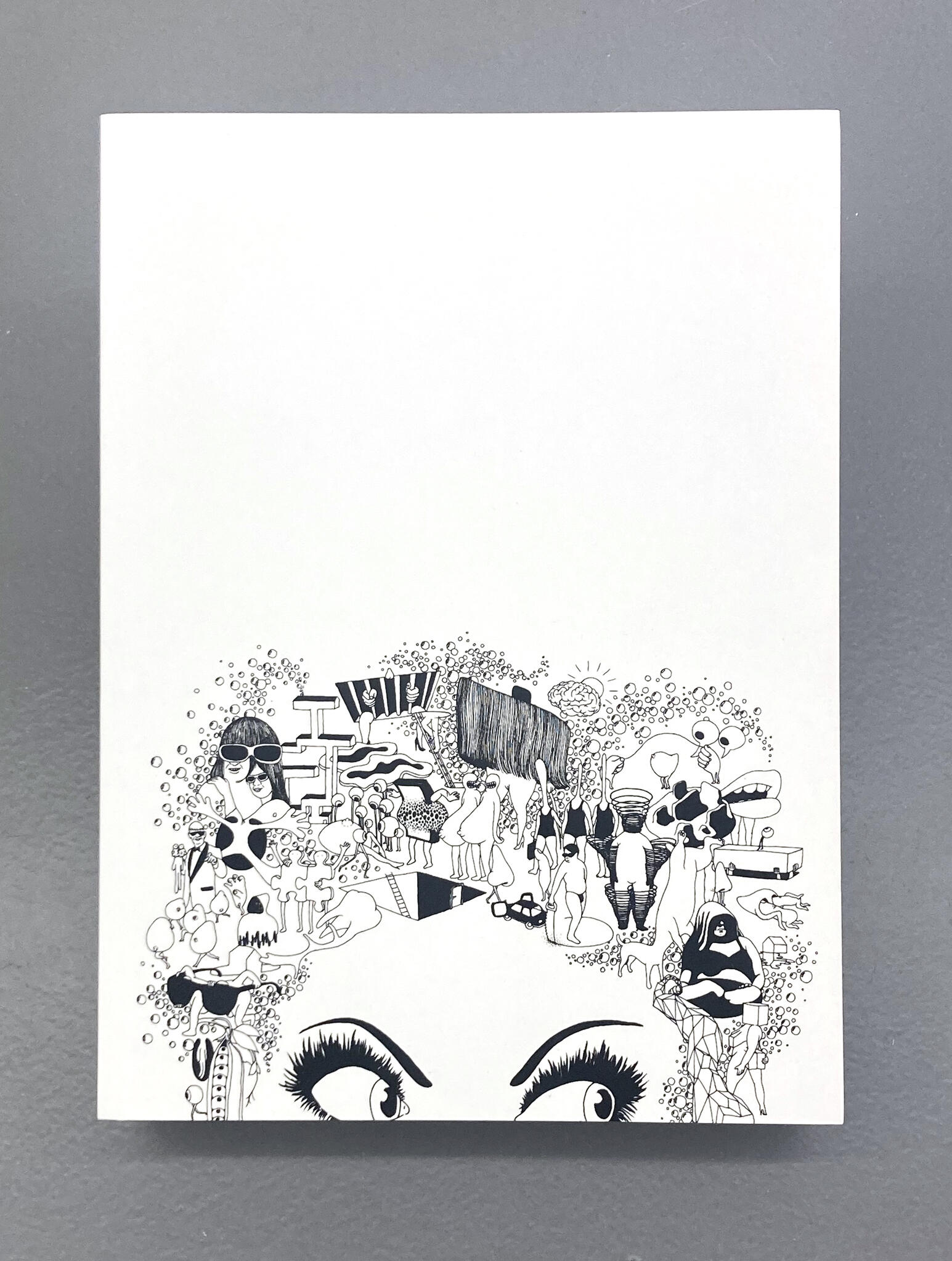

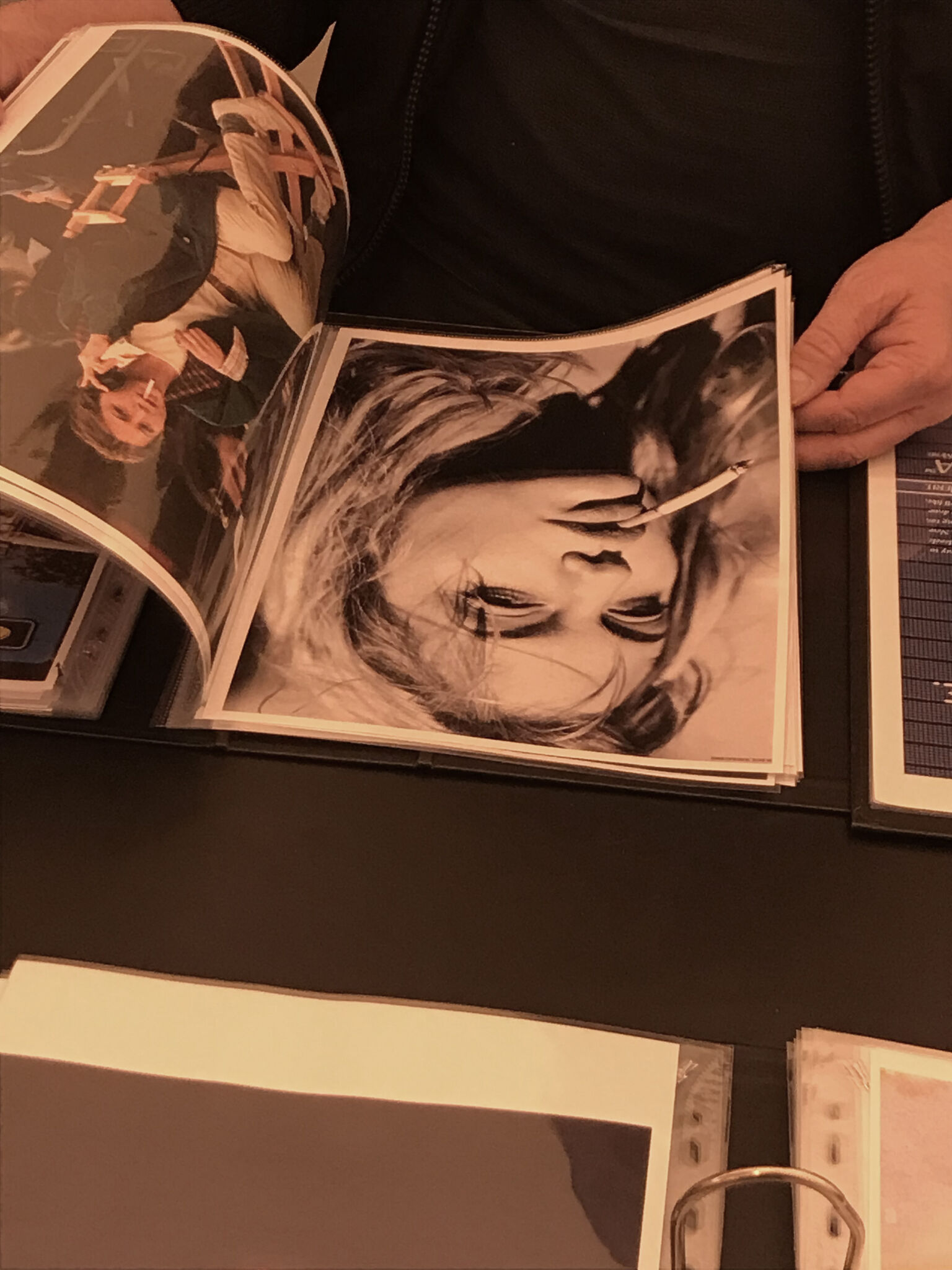

Les 120 classeurs et 9600 images qui constituent aujourd’hui le projet The Tobacco Files de Laëtitia Badaut Haussmann rappellent volontairement l’art conceptuel des années 1970 (au passage, une histoire majoritairement occidentale, masculine et blanche) où l’emprunt d’une esthétique administrative détourna efficacement l’art de l’expressivité comme gage du moi créateur. Dans les années 1980, de jeunes artistes (comptant cette fois de nombreuses femmes), ont continué d’attaquer le mythe de l’originalité en reprenant directement des images dans la publicité et la culture commerciale pour en faire des œuvres d’art. L’une des œuvres inaugurales de cet art de l’appropriation n’est autre que le recadrage, par Richard Prince, d’une réclame Marlboro figurant le fameux cow-boy, débarqué dans l’imaginaire de la marque pour masculiniser la clientèle des cigarettes filtre.

L’ambiance ambrée qu’installe Laëtitia Badaut Haussmann dans l’espace d’exposition nous enrobe d’une sensation douteuse, entre le souvenir d’un wagon fumeur et l’idée d’un plateau de tournage pour une scène en extérieur nuit. C’est ainsi qu’un simple geste pour modifier l’éclairage déplace l’expérience froide de l’art conceptuel dans une douce torpeur.

Le fait que cette recherche ait commencé à Vienne a son importance. Cela a permis de refaire le chemin qui mène de l’invention de la psychanalyse à celle des démocraties capitalistes. En effet, c’est sur la théorie de l’inconscient élaborée par son oncle Sigmund Freud que s’appuient les stratégies du publicitaire d’Edward Bernays transposées dès les années 1930 dans la politique (1). Cela consiste à garantir la paix par le contrôle des masses en fabriquant des désirs de consommation et en leur permettant de les assouvir partiellement. Le terme choisi à l’époque pour ce procédé est “l'ingénierie du consentement”.

Ces notions sont inscrites dans la définition de l’image publicitaire que fait l’auteur marxiste John Berger dans son célèbre essai de didactique des images “Voir le voir” (2) : “Le glamour existe seulement si l’envie sociale devient une émotion personnelle commune et généralisée. La société industrielle qui a évolué dans le sens de la démocratie - et qui s’est arrêtée à mi-chemin - est la société idéale pour faire naître ce genre d'émotions. La recherche du bonheur a été reconnue comme un droit universel. Cependant, les conditions sociales existantes font que l’individu se sent impuissant. Il vit entre la contradiction de ce qu’il est et de ce qu’il voudrait être. Et alors, ou bien il devient pleinement conscient de la contradiction et des causes et s’engage ainsi dans la lutte politique visant à une véritable démocratie qui, entre autres choses, requiert la destruction du capitalisme; ou bien il vit en proie à une sentiment permanent d’envie qui, combinée à la conscience de son impuissance, se dissout dans un rêve éveillé perpétuellement recommencé”.

Alors que cette dernière phrase résonne étrangement avec l’exposition de Laëtitia Badaut Haussmann, l’on note comment l’industrie du tabac et le motif de la cigarette offre une entrée majeure dans la compréhension de la construction du néolibéralisme et comment il croise les questions liées aux images, à l’émancipation ou aux affects. La cigarette se fait l'emblème de la névrose ordinaire de la société moderne : issue d’une industrie opaque qui a diffusé le plus d’images dans l’espace public, associant les notions de pouvoir et de liberté à un produit hautement addictif qui détruit le corps de l’intérieur, sur ce modèle dialectique, la liste pourrait être longue… Alors même que nos sociétés contemporaines tendent vers un “monde sans tabac”, il subsistent de cet ancien monde des réalités et des fantômes. C’est précisément ces signes de survivance du passé et la manière dont ils façonnent notre expérience du présent que met en lumière le travail de Laëtitia Badaut Haussmann.

Pour elle, le coup publicitaire organisé par Bernays en 1929 au service de la compagnie américaine de tabac, “The Torch of Freedom”, pourrait être le véritable premier happening de l’histoire moderne. Bernays avait recruté un échantillon représentatif de femmes américaines (en insistant pour qu’il y figure des féministes) afin qu’elles déambulent en fumant dans les rues de New York lors de la parade de Pâques. Ainsi faisait-il entrer la moitié de la population qui manquait à la clientèle des cigarettiers, et introduisait dans l’imaginaire collectif la figure de la fumeuse comme femme de pouvoir. En outre, il existe de nombreux points de rencontre entre le tabac et l’histoire de l’art. C’est la contribution financière de la firme Philip Morris qui a rendu possible la réalisation de l’exposition séminale “Quand les attitudes deviennent forme” à la Kunsthalle de Bern en 1969 en payant les billets d’avion des artistes. Dès lors, une exposition pouvait présenter des œuvres qui n’étaient pas des objets mais le résultat de l’intervention d’un artiste, son geste “in situ”.

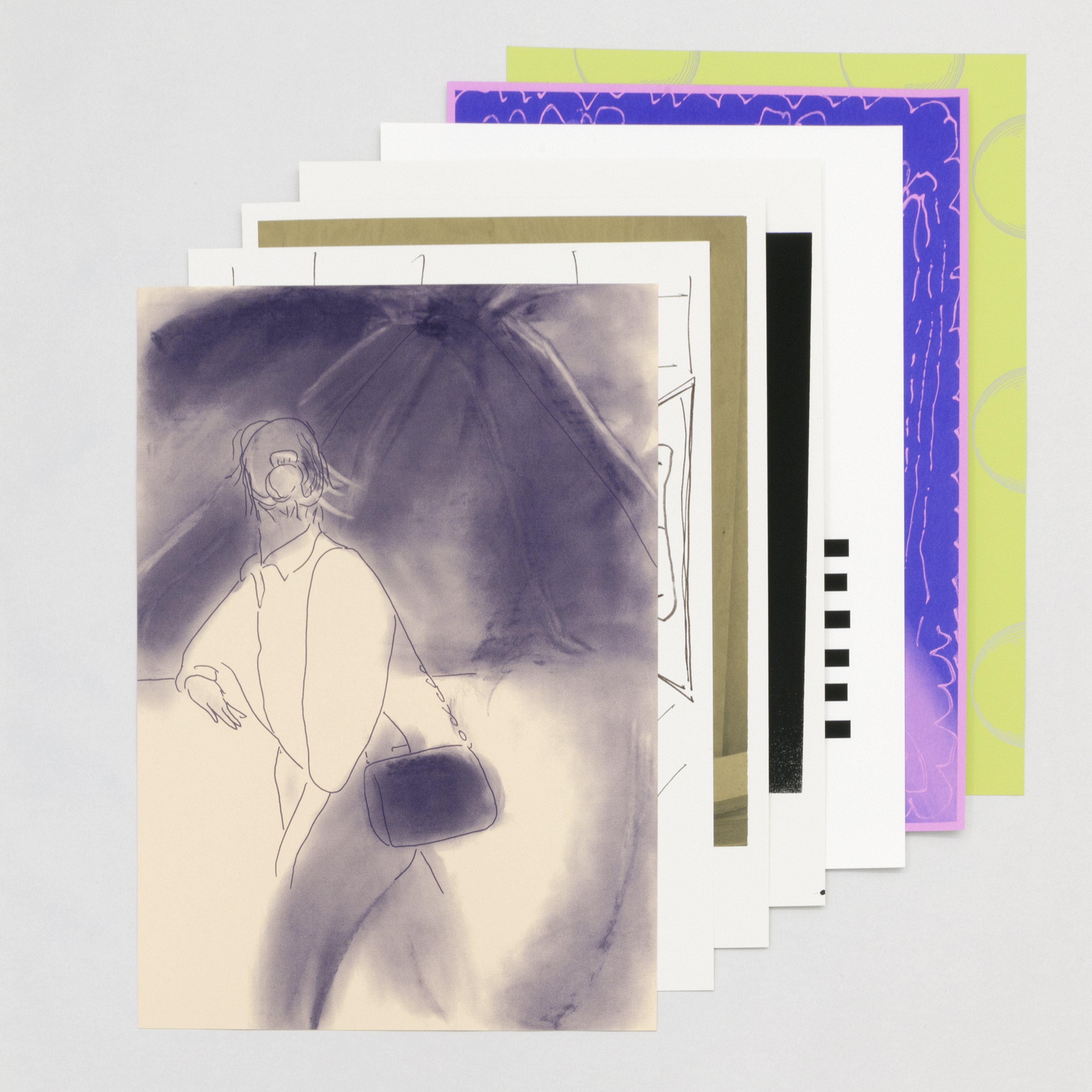

Si feuilleter les Tobacco Files offre une traversée de l’histoire des représentations liées au tabac, son projet n’est pas d’articuler cette histoire de manière exhaustive. La collection dans sa dimension quantitative pourrait elle aussi être vue comme un geste, un geste de sculpture, activant le regard par les motifs du plein et du creux, du visible et de l’invisible. Chaque image pourrait faire l’objet d’un décryptage, ce qui aujourd’hui pose la question de savoir s’il on est capable de définir l’identité du récepteur. À l’heure où la circulation des images n’est plus traçable, qu’elles transitent de sphères privées en sphères publiques, ressurgissent sous forme de mème au hasard des algorithmes, c’est plutôt la manière dont certaines images remontent ou non dans le moteur de recherche d’une femme artiste blanche occidentale qu’analyse Laëtitia Badaut Haussmann; ainsi la collection se poursuit-elle avec les contributions de personnes issues de différents milieux, territoires, genres, générations.

Some visitors regret the absence of a sign that could make La Salle de bains more visible from rue Louis Vitet. It’s true that the association has never obtained an authorization along those lines. The piece of sculpture installed on the façade during the run of Laëtitia Badaut Haussmann’s show is an authentic Austrian sign from a classic tobacconist-newsagent’s, purchased on the second-hand market. In Vienna, while the artist was exhibiting the initial results of her work on tobacco, the sign instantly caused an alert and was removed in the presence of a sworn agent of the state-run Austria Tabak company. Just the kind of thing for pondering the agency of the readymade within the context of its presentation, but especially the authority of certain signs, even when they look used, and the way they govern public space, right down to the courtyard of a community art space.

The 120 binders and 9600 images that currently make up Haussmann’s The Tobacco Files consciously recall the conceptual art of the 1970s (by the way, a story that is largely Western, male, and White), where a borrowednadministrative aesthetic effectively reappropriated expressiveness as a token of the creative ego. In the 1980s, young artists (including many women this time) continued to attack the myth of originality by lifting images directly from advertising and business culture and transforming them into works of art. One of the inaugural works of this art of appropriation is none other than Richard Prince’s reframing of a Marlboro ad featuring the famous cowboy, who rode into the brand’s imagery in order to masculinize the clientele of filtered cigarettes.

The amber atmosphere Haussmann has created in the exhibition space wraps us in a dubious sensation, something between the memory of a smoking car and the idea of a film set for an outdoor nighttime scene. Thus, a simple gesture modifying the lighting tips the cool experience of conceptual art over into a gentle torpor.

The fact that this development in Haussmann’s art started in Vienna is not without significance. It makes it possible to retrace the path leading from the invention of psychoanalysis to that of capitalist democracies. It was indeed the theory of the unconscious worked out by his uncle Sigmund Freud that underpinned Edward Bernays’s public relations strategies, which began to be applied to politics in the 1930s.(1) This consisted of guaranteeing peace through control of the masses by producing consumer desires and allowing those masses to partly satisfy them. The expression of choice in those days was engineering consent.

These ideas are an integral part of the definition of the advertising image proposed by the Marxist author John Berger in his famous essay on the didactics of images, Ways of Seeing: “Glamour cannot exist without personal social envy being a common and widespread emotion. The industrial society which has moved towards democracy and then stopped half way is the ideal society for generating such an emotion. The pursuit of individual happiness has been acknowledged as a universal right. Yet the existing social conditions make the individual feel powerless. He lives in the contradiction between what he is and what he would like to be. Either he then becomes fully conscious of the contradiction and its causes, and so joins the political struggle for a full democracy which entails, amongst other things, the overthrow of capitalism; or else he lives, continually subject to an envy which, compounded with his sense of powerlessness, dissolves into recurrent daydreams.”(2)

While that last sentence strangely resonates with Haussmann’s show, we should note how the tobacco industry and the cigarette motif offer a matchless way into understanding the construction of neoliberalism and how it brings together questions touching on images, emancipation and affects. The cigarette is the emblem of modern society’s ordinary neurosis. It comes from murky industry that has flooded public space with the greatest number of images, associating ideas of power and liberty with a highly addictive product that destroys the body from the inside – on this dialectic model, the list could easily go on… Even if our contemporary societies are moving towards a “tobacco-free world,” there lingers certain realities and ghosts from the old world where tobacco was king. It is precisely these signs of survival of the past and the way they mold our experience of the present that Haussmann’s work brings to light.

For her, the advertising coup that Bernays brought off in 1929 for the American tobacco company “The Torch of Freedom” could be the first true happening of modern history. Bernays had recruited a representative sample of American women (insisting that feminists be included) to walk around the streets of New York during the Easter parade while smoking. And thus he managed to pull in the half of the population that was missing from the cigarette companies’ clientele and introduce into the collective imagination the figure of the smoking female as a powerful woman. Moreover, there exist numerous points where tobacco and art history meet. It was the financial support of the Philip Morris Company, for instance, that made it possible to mount the seminal show “When Attitudes Become Form” at Bern’s Kunsthalle in 1969 by paying the invited artists’ airfare. After that date, an exhibition could present artworks that were not objects but rather the result of artists’ interventions, their “site-specific” gestures.

If paging through The Tobacco Files offers a long look at the history of representation with strong links to tobacco, the artist’s project is not to articulate this history exhaustively. The collection could also be viewed quantitatively as a gesture, a sculptural gesture, activating the eye through certain motifs, i.e., full and hollow, visible and invisible. Each image could be approached as something to be decrypted, which raises the question today of whether the receiver can be in fact identified. In an age when the circulation of images is no longer traceable, when they move from the private to the public sphere and pop back up in the form of a meme fashioned by random selections made by algorithms, it is more the way some images resurface or not in the search engine of a Western White woman artist that Haussmann is intent on analyzing. And so the collection continues with contributions of people from different milieux, places, genders, and generations.

Translation : John O'Toole

(1) Voir les documentaires pour la BBC d’Adam Curtis, The century of the self, 2002.

(2) John Berger, Voir le voir, B42, 2014 (1972).

(1) See Adam Curtis’s documentaries for the BBC, The Century of the Self, 2002.

(2) See Ways of Seeing, John Berger’s 1972 BBC series and subsequent book.

Liste des œuvres :

List of works :

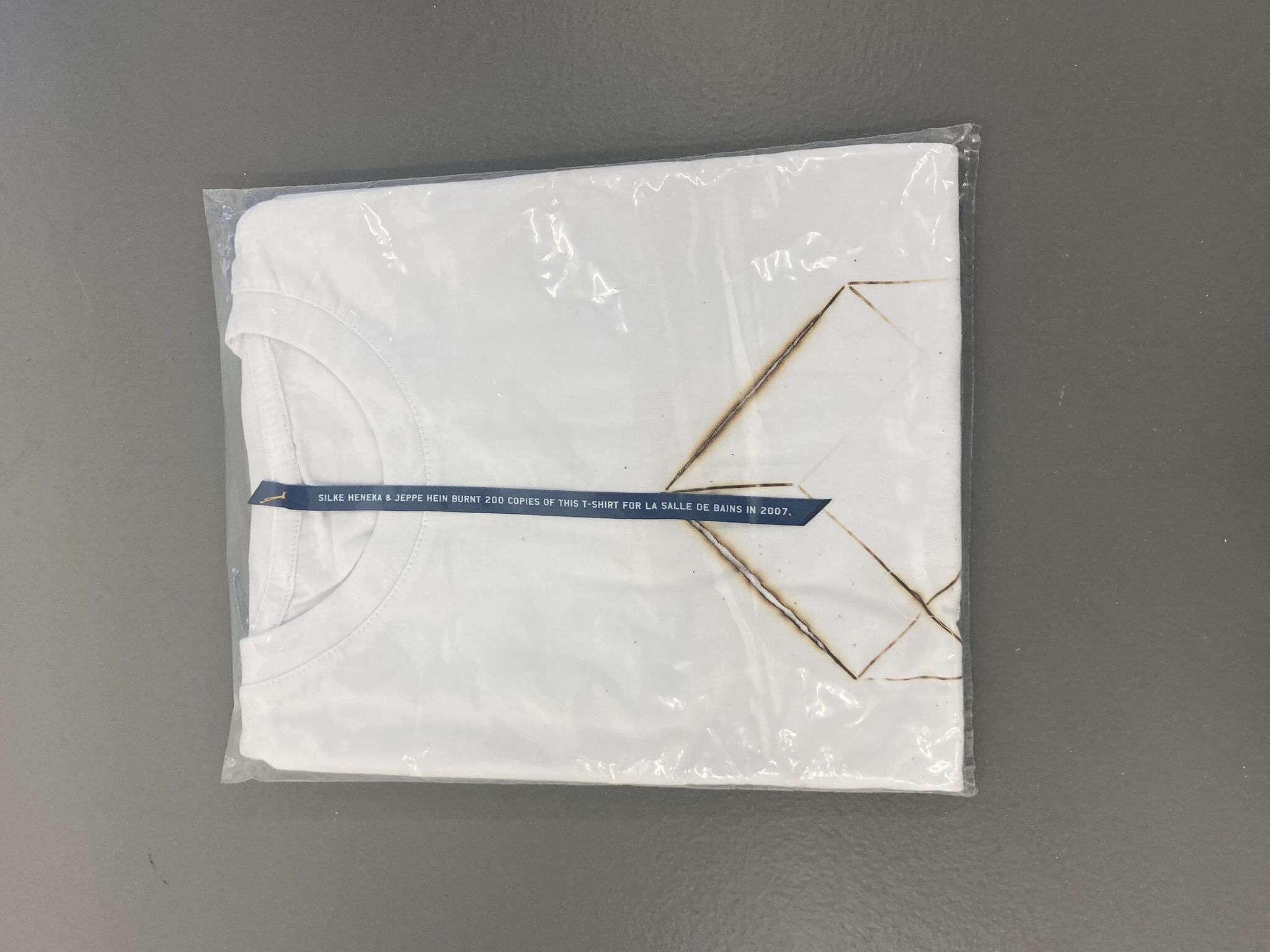

Enseigne d’occasion Austria Tabak en métal,

peinture epoxy, 60 x 130 x 20cm

Courtesy de l'artiste, galerie Allen, Emanuela Campoli, EDB Projects

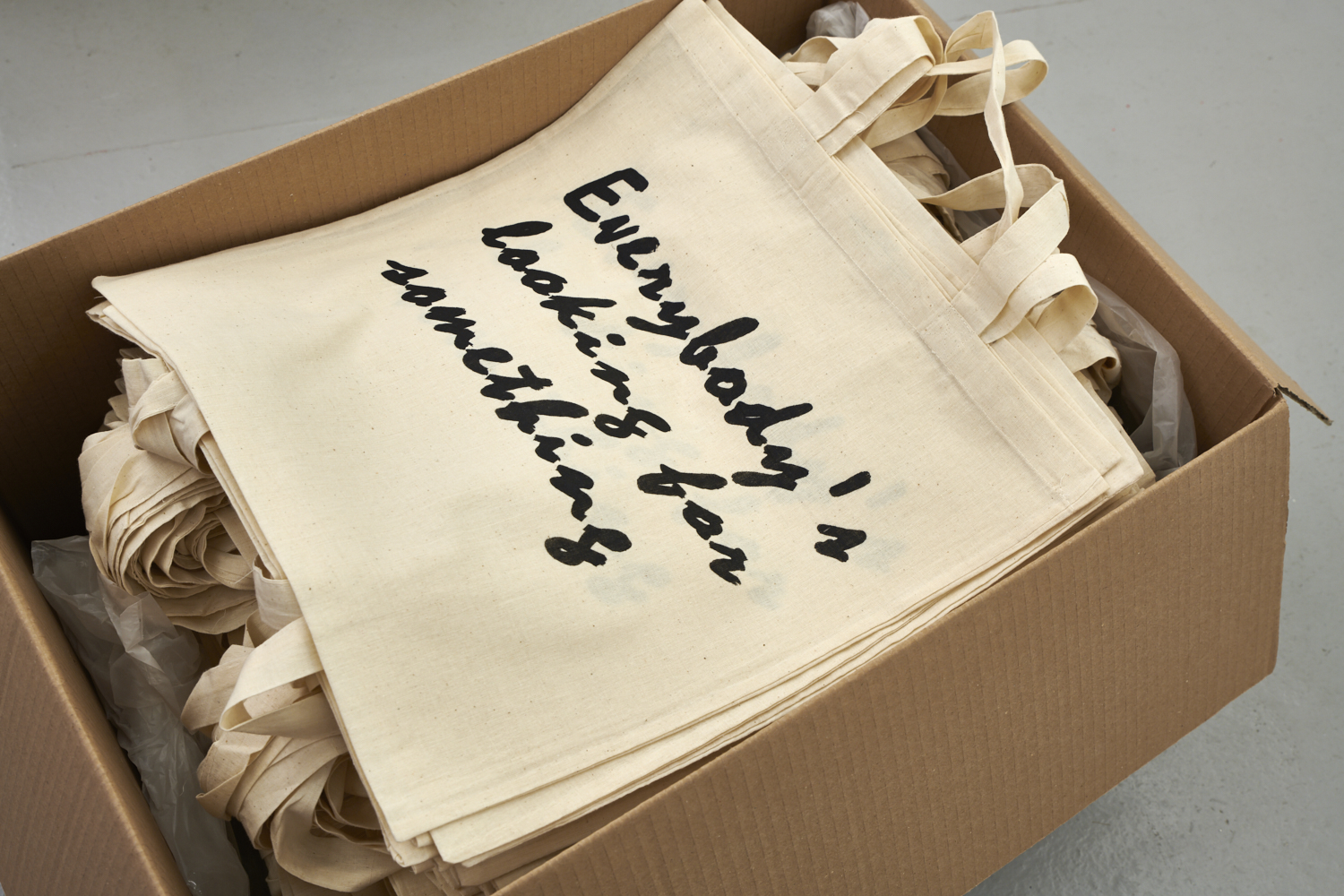

The Tobacco Files, 2022-2023

9600 impressions A4 couleur,

120 classeurs noirs, dimensions variables

Co-production Fonds de dotation Franklin Azzi

Courtesy de l'artiste, galerie Allen, Emanuela Campoli, EDB Projects

Smoking in the streets of Vienna (Anonyme 136), 2022

Photographie, 15 x 10 cm

Co-production Fonds de dotation Franklin Azzi

Courtesy de l'artiste, galerie Allen, Emanuela Campoli, EDB Projects

L’installation comprend également des gélatines couleurs ambre qui recouvrent les néons, 3 tables Eiermann 1 de Richard Lampert et les cartons de stockage des Tobacco Files. Ces éléments font partie de l’installation de l’artiste à la Salle de bains.

Sign Austria Tabak metal, epoxy paint, 60 x 130 x 20cm

Courtesy of Laëtitia Badaut Haussmann, the Allen Gallery, the Emanuela Campoli Gallery and EDB Projects.

The Tobacco Files, 2022-2023

9600 A4 colour prints, 120 black binders, variable dimensions. Co-production Franklin Azzi Endowment Fund

Courtesy of Laëtitia Badaut Haussmann, the Allen Gallery, the Emanuela Campoli Gallery and EDB Projects.

Smoking in the streets of Vienna (Anonyme 136), 2022

Photograph, 15 x 10 cm.

Co-production Franklin Azzi Endowment Fund

Courtesy of Laëtitia Badaut Haussmann, the Allen Gallery, the Emanuela Campoli Gallery and EDB Projects.

The installation also includes amber-coloured gelatin covering the neon lights, 3 Eiermann 1 tables by Richard Lampert and the Tobacco Files storage boxes. These elements are part of the artist's installation at the Salle de bains.

Les recherches et productions de Laëtitia Badaut Haussmann évoluent à l'intersection de plusieurs champs dont la domesticité, la psychologie, les cultural studies et le féminisme, explorant un ensemble de de problématiques liés à l'habitus, à la circulation des biens et aux typologies de gestes. Sa pratique artistique s'articule autour de la notion de para-architecture (ce qui se situe à côté ou au- delà de l'architecture), qu'elle envisage comme une méthode de travail. Laëtitia Badaut Haussmann recourt à la sculpture, l'image, le texte, la vidéo, le son, tout en favorisant l'installation, l'exposition étant son principal médium.

Née en 1980 à Paris, Laëtitia Badaut Haussmann vit et travaille à Paris.

Elle a présenté son travail dans des expositions personnelles et collectives, notamment au Palais de Tokyo (2010), au Centre Pompidou Metz (2017), au MUDAM (2017), au MUSEION (2017), Kettle’s Yard (2018), Musée départemental d’art contemporain de Rochechouart (2018), MRAC (2019), MACRO (2020), The Community (2021), EDB Projects (2021), Fondation Pernod Ricard (2021), Musée d’Art Moderne (2021), Frac Pays de la Loire (2023), CAPC (2023). Laëtitia Badaut Haussmann est représentée par les galeries Allen (Paris), Emanuela Campoli (Paris et Milan) ainsi que Ellen de Bruijne (Amsterdam).

Elle est lauréate du prix Aware 2017. Elle a enseigné à l’Université Paris-Diderot et à la Parson Paris - la Nouvelle École.

Born in Paris in 1980, Laëtitia Badaut Haussmann lives and works in Paris. She holds a DNSEP from the Ecole nationale supérieure d'arts de Cergy in 2006.

Her work was presented in solo and group exhibitions, notably at Palais de Tokyo (2010), Centre Pompidou Metz (2017), MUDAM (2017), MUSEION (2017), Kettle's Yard (2018), Musée départemental d'art contemporain de Rochechouart (2018), MRAC (2019), MACRO (2020), The Community (2021), EDB Projects (2021), Fondation Pernod Ricard (2021), Musée d'Art Moderne (2021), Frac Pays de la Loire (2023), CAPC (2023).

She has been a professor at Université Paris-Diderot and at the Parson Paris - la Nouvelle École. She won the Aware prize in 2017.

Laëtitia Badaut Haussmann is represented by the galleries : Allen (Paris), Emanuela Campoli (Paris and Milan) and Ellen de Bruijne (Amsterdam).

de la Région Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes et de la Ville de Lyon.