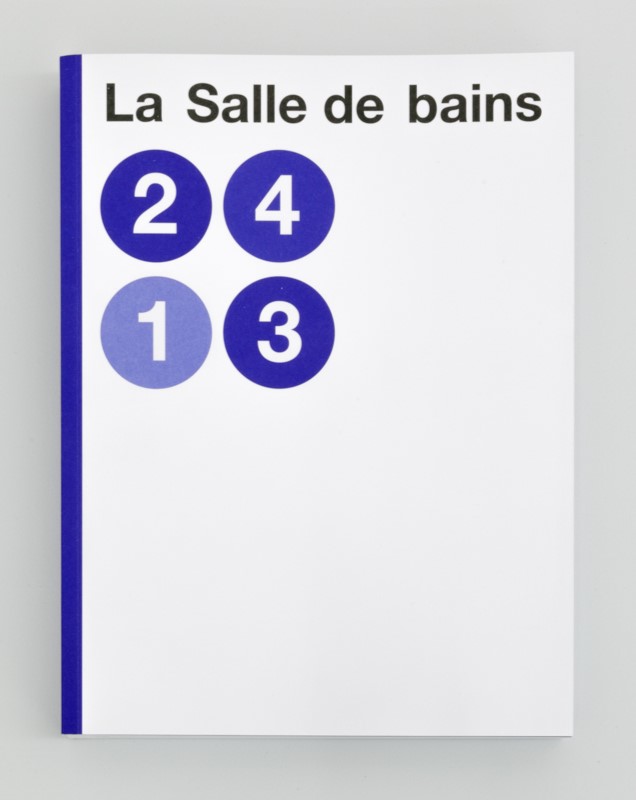

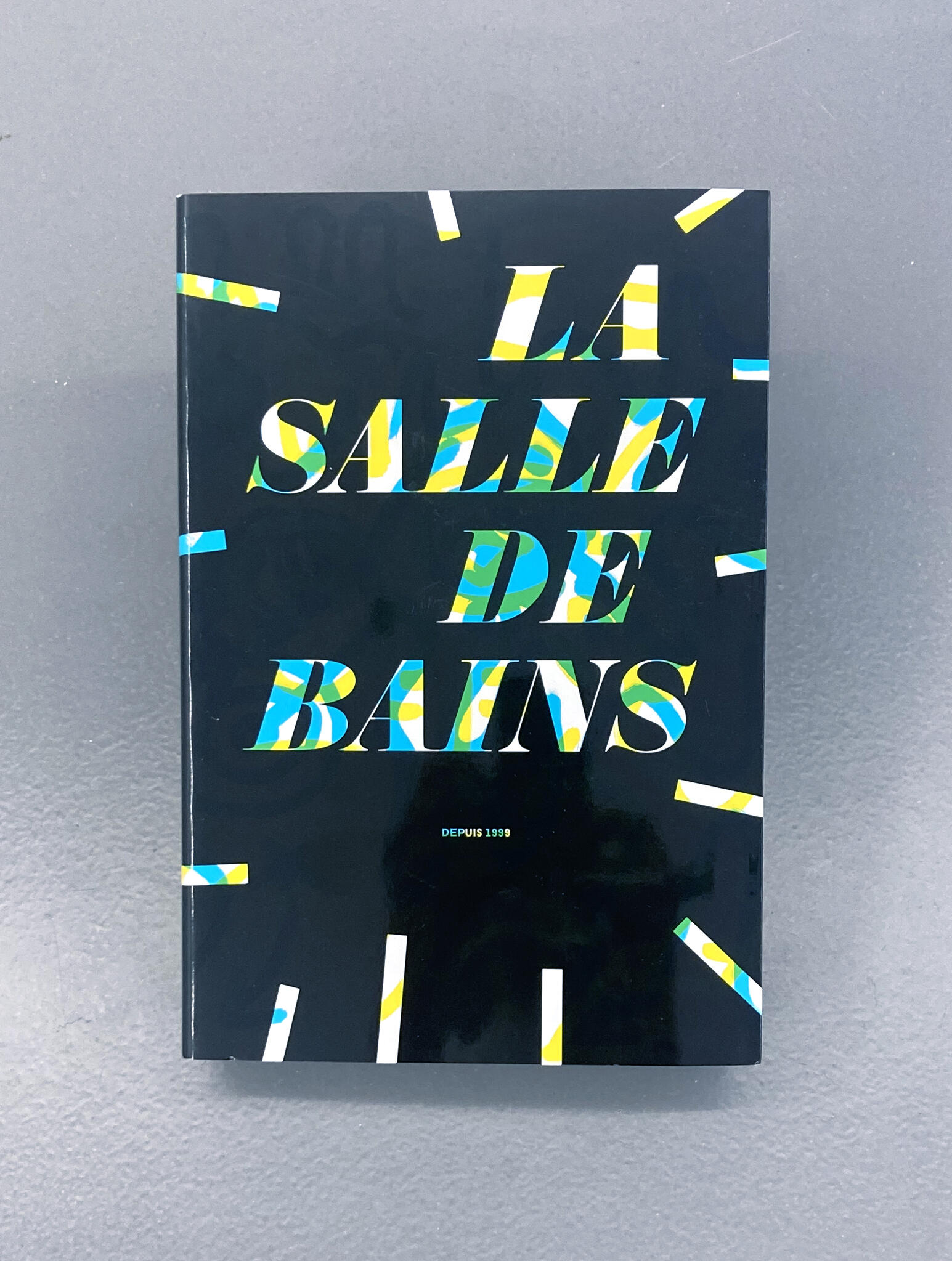

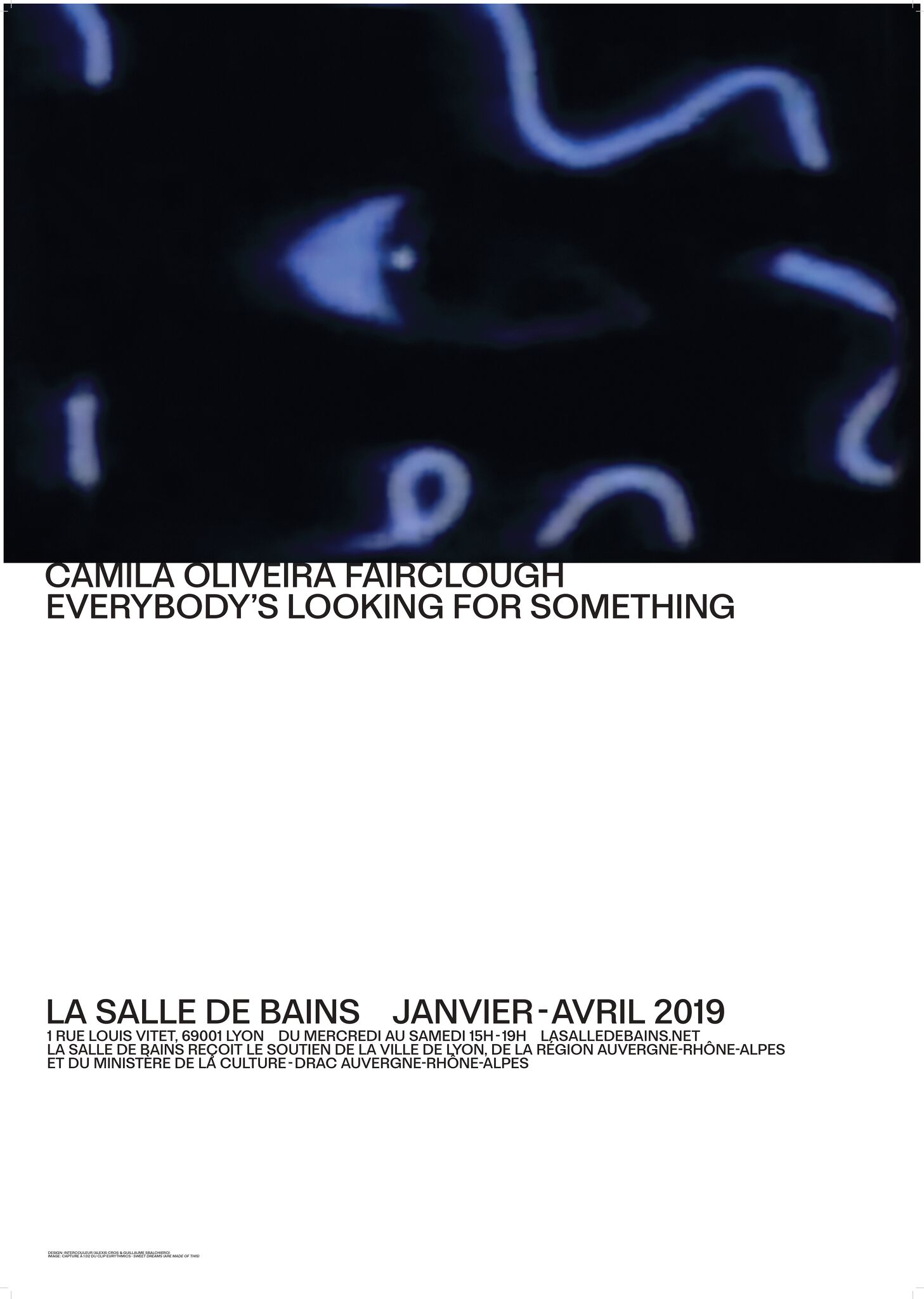

Everybody's looking for something - salle 2 (everything must go), Camila Oliveira Fairclough, la Salle de bains, Lyon du 21 février au 2 mars 2019.

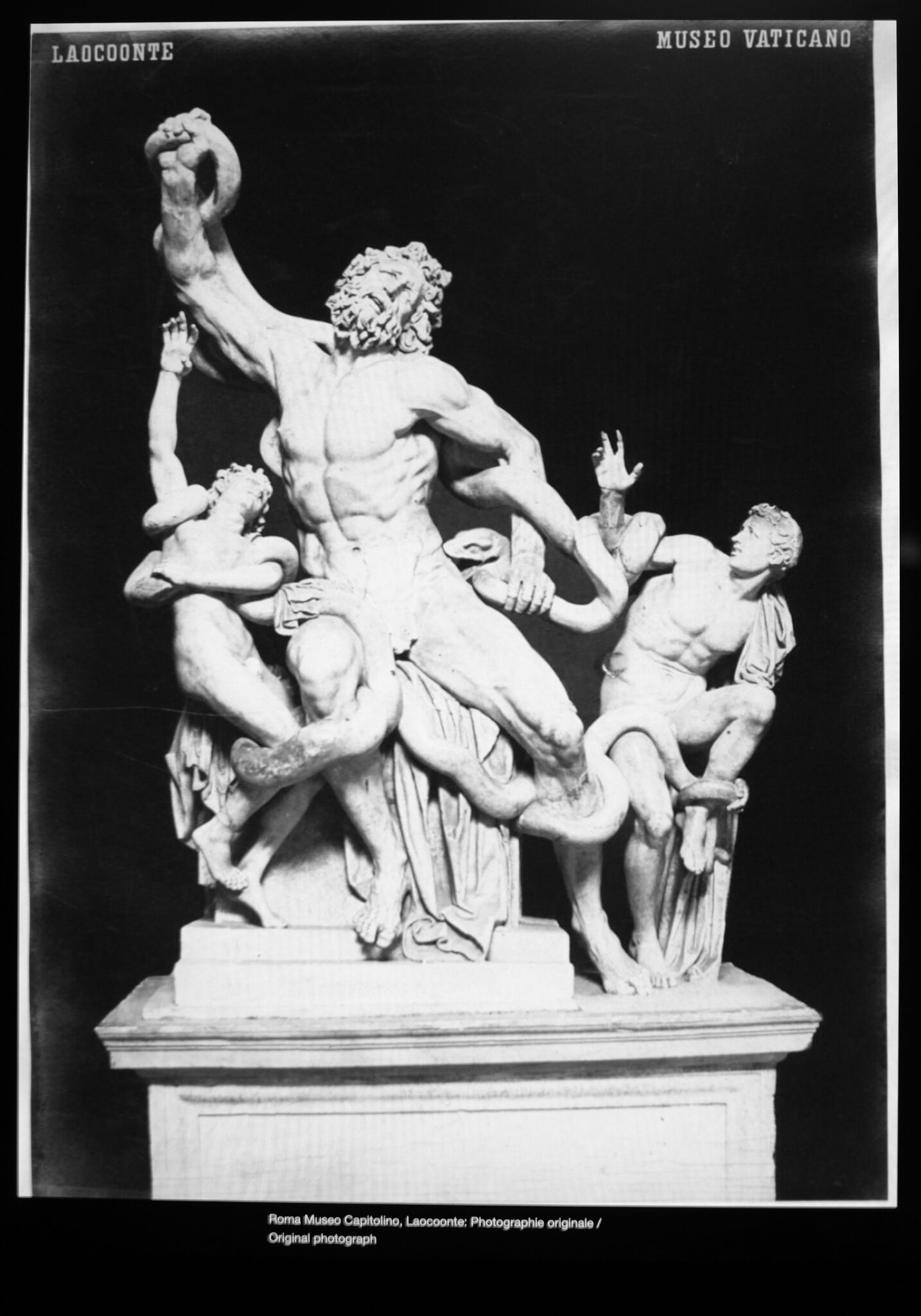

Photos : Jules Roeser

Photos : Jules Roeser

Everybody's looking for something - room 2 (everything must go), Camila Oliveira Fairclough, la Salle de bains, Lyon from 21 February to 2 Mach 2019.

Photos : Jules Roeser

Photos : Jules Roeser

Everybody's looking for something - salle 2 – (everything must go)

Du 21 février au 2 mars 2019From 21 February to 2 March 2019

La première salle de l’exposition Everybody’s Looking for Something présentait cinq peintures récentes de Camila Oliveira Fairclough. L’accrochage rigoureux pouvait contraster avec une certaine nonchalance que ces peintures inspirent au premier abord. Ainsi du choix des motifs génériques (cœur, emoji, numéros) ou empruntés à un environnement visuel et linguistique ordinaire, comme s’il n’y avait, en peinture, que des sujets valables. Quant à la technique, par certains aspects, elle semble exprimer chez Camila Oliveira Fairclough une insouciance qui va jusqu’à laisser visibles les traits de crayon du dessin, comme si le fini et le non fini étaient équivalents. Elle relève bien au contraire d’une grande maîtrise du geste, où toutes les modulations (vitesse du pinceau, quantité de peinture) font l’objet de décisions précises, tandis que la spontanéité est toujours doublée d’une approche analytique instruite de toute l’histoire de la peinture moderne. Ainsi cette poétique de l’ambivalence se donnait-elle dans un accrochage froid et sucré, où l’appétence pour la peinture et les choses de la vie pouvait nous atteindre au travers d’un système normé (le tableau, l’exposition) et même l’identification d’autres systèmes de production de valeur et de désir (le design publicitaire, le sondage de la satisfaction du client). Le sous-titre (love, food, money) pouvait donc résonner avec l’éloquence de tableaux comme Sunday Brunch ou Avec ou sans contact.

Il était plus périlleux d’établir un rapport avec le refrain des Eurythmics ou même la musique new wave, à moins de pousser l’analyse de cette couleur étrange choisie pour y accrocher les tableaux : un mauve iridescent aux connotations confuses (electro-pop tirant sur le glam-rock, punk-gothique, pouvant évoquer la décoration d’un bar à chicha ou d’un « point soleil »). Elle avait pour effet de tester la manière dont la peinture résiste, avec peu de moyens, aux sollicitations du mur et aux imprévus. Le texte qui accompagnait la salle 1 en proposait une interprétation littérale, ce qui n’écarte jamais définitivement les affres de l’équivocité qu’escortent souvent les tourments de la tautologie : la formule générique, prise au pied de la lettre et dans les circonstances présentes, exposait l’exposition elle-même à la question de ce que viennent y chercher les visiteurs, supposant que l’œil, devant la peinture, est un organe insatiable et que son avidité diffère sans cesse le moment de se demander ce qu’on attend (encore) de l’art.

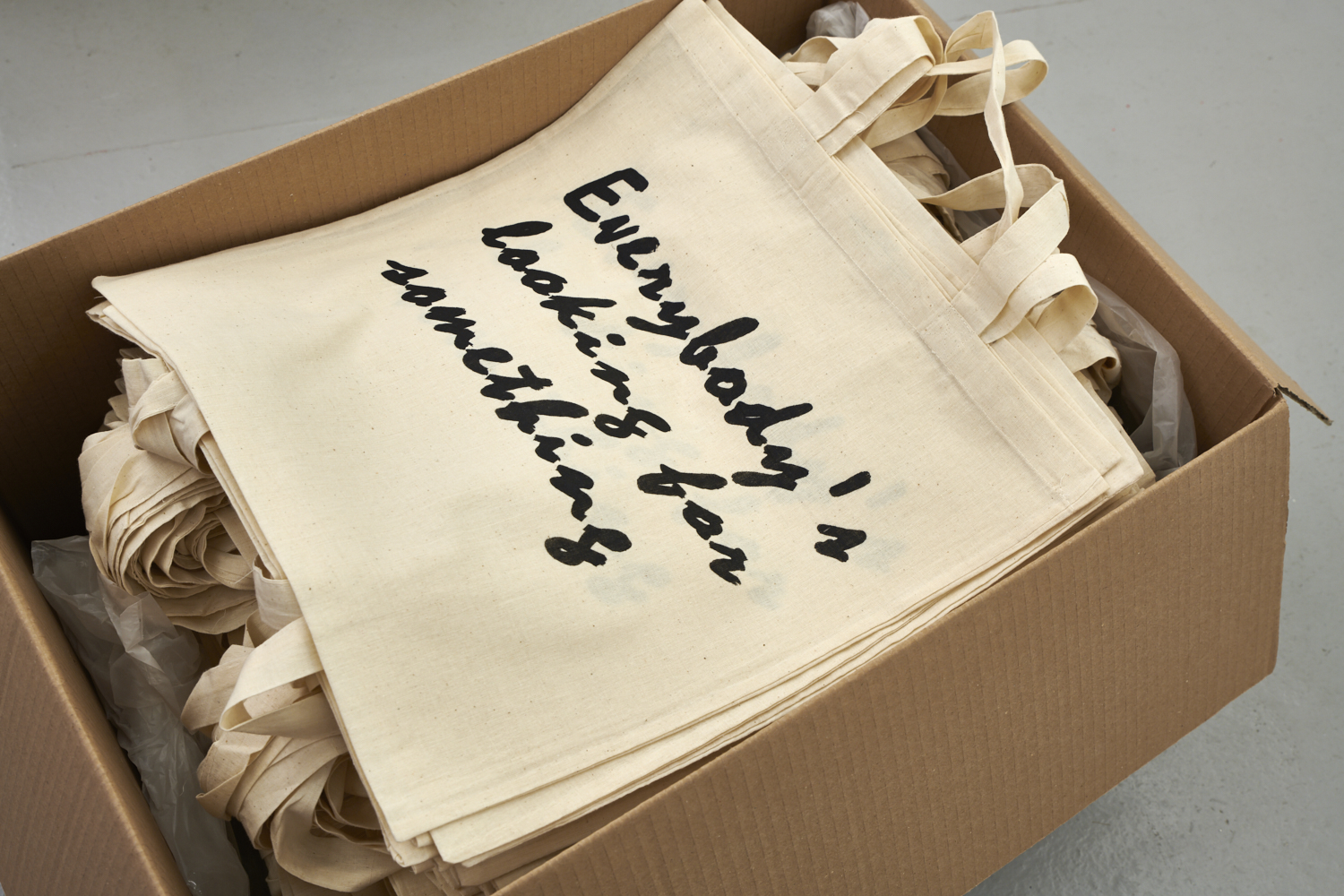

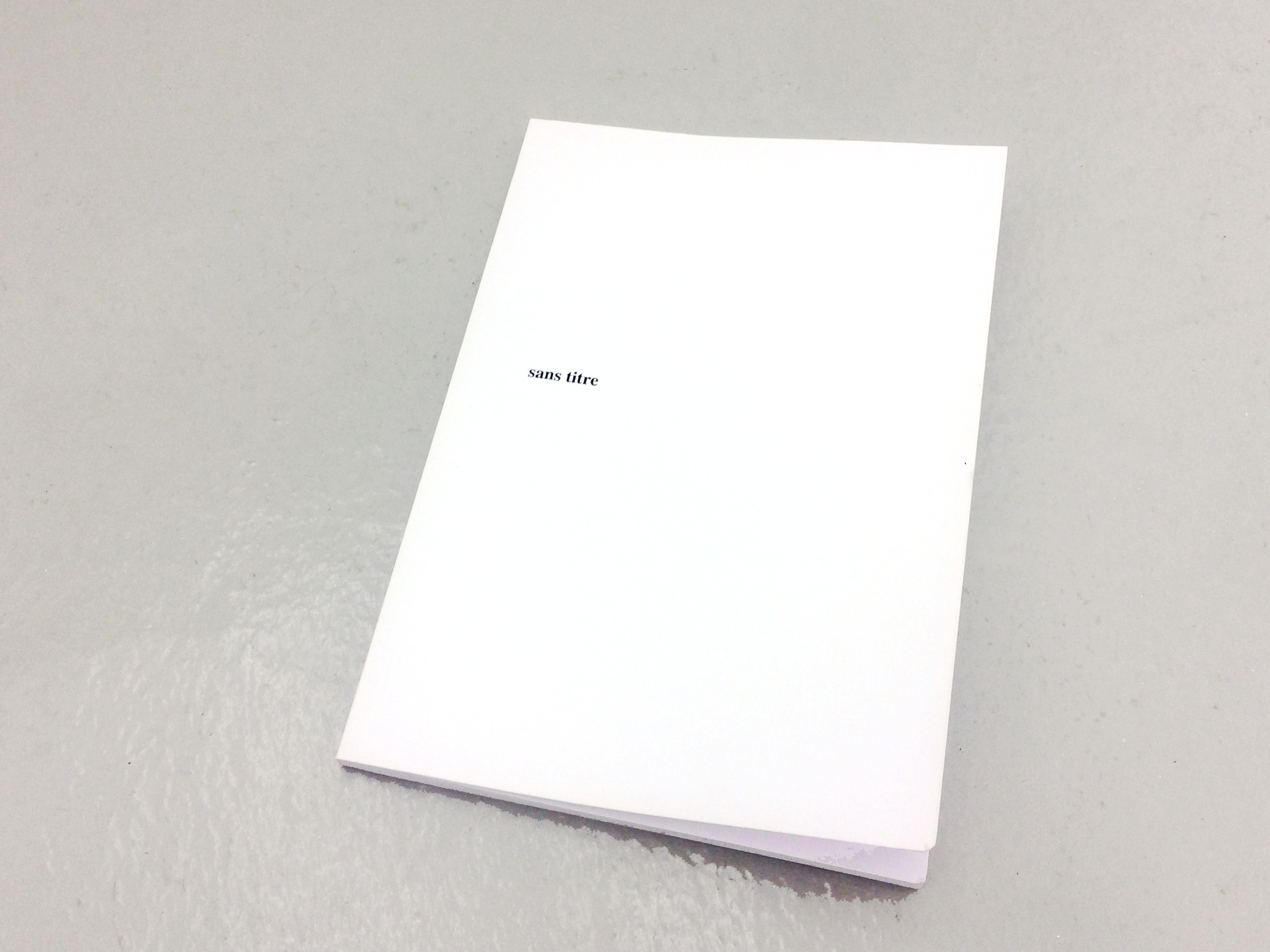

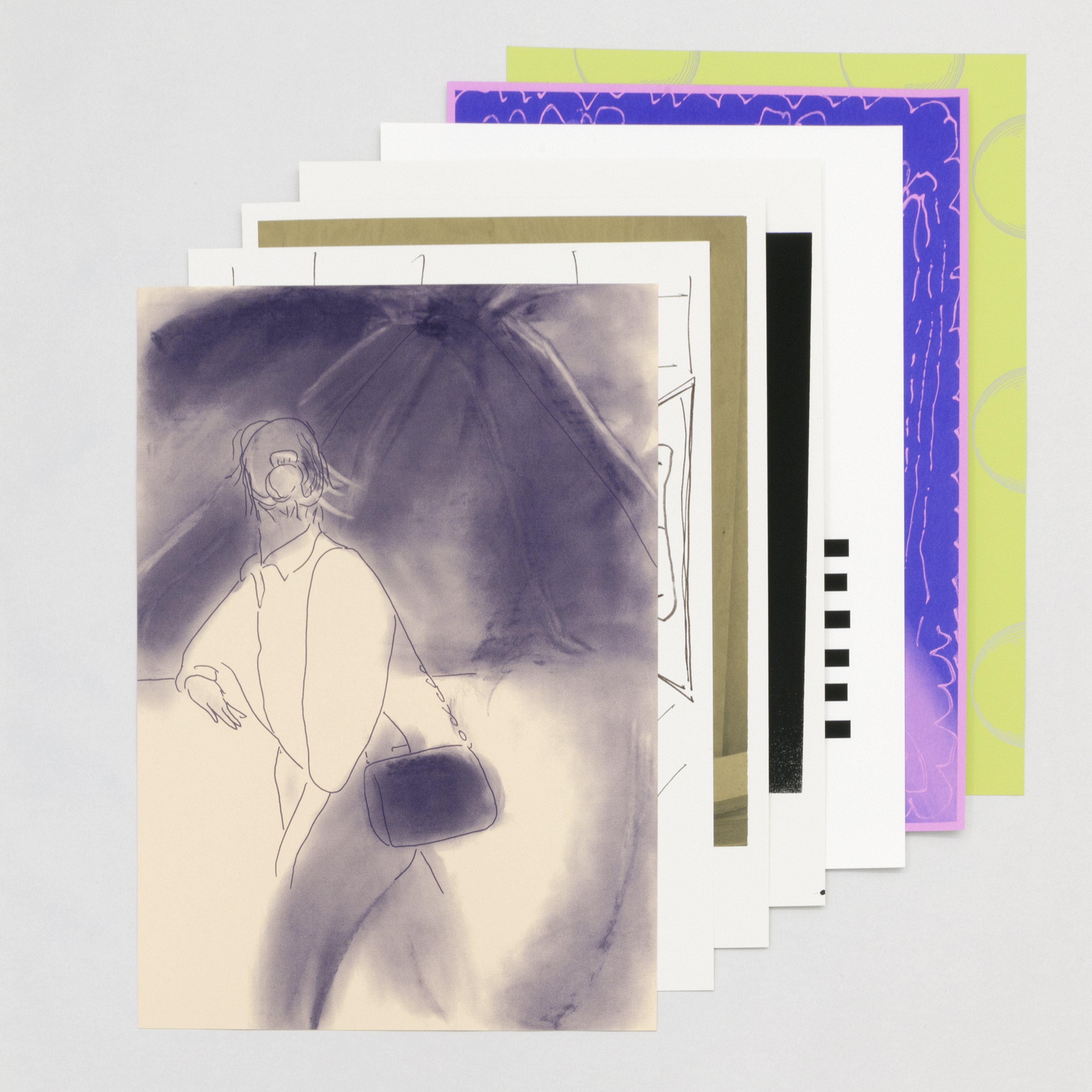

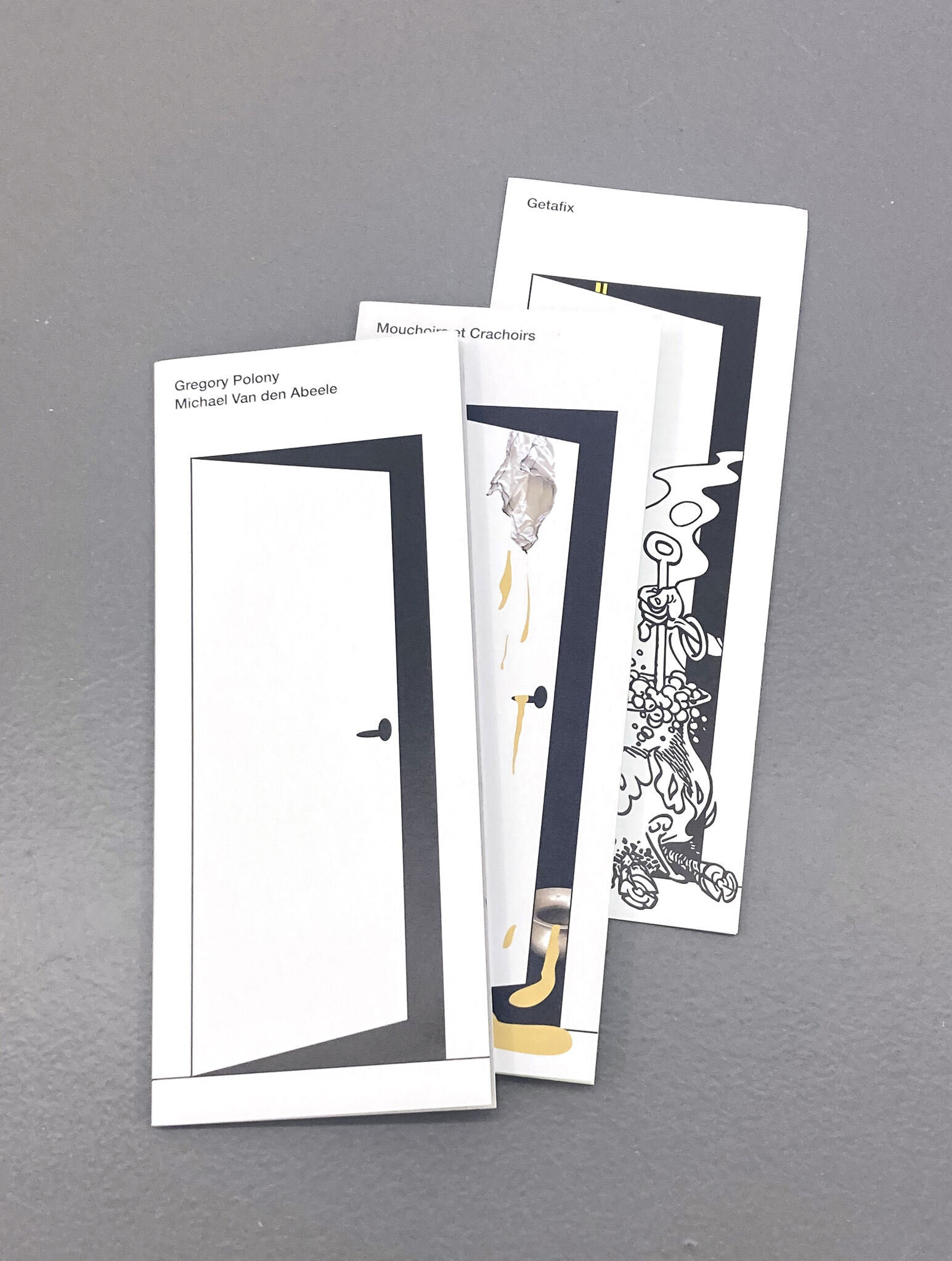

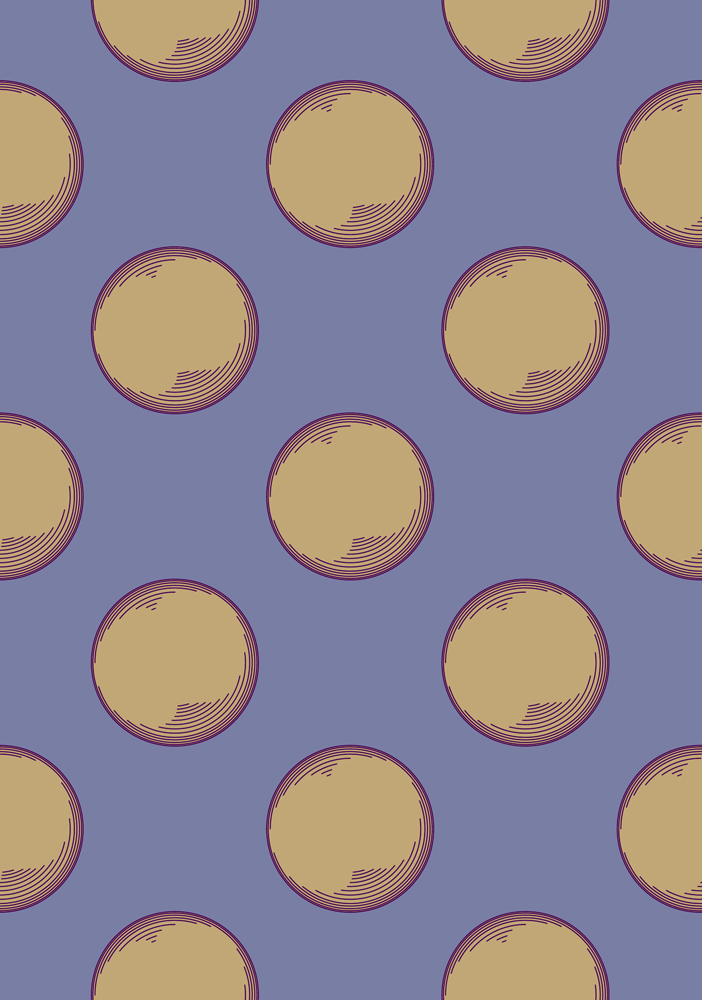

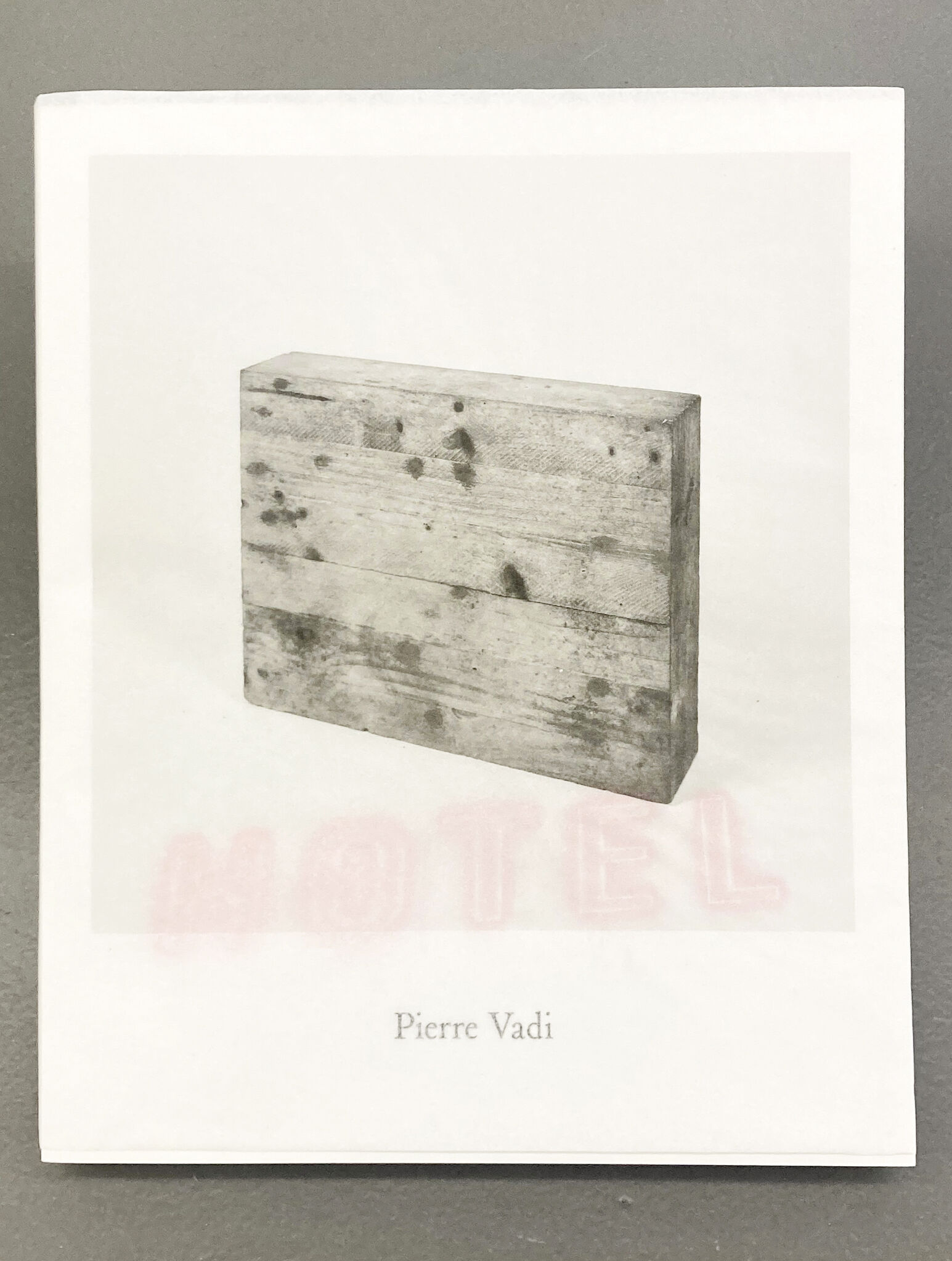

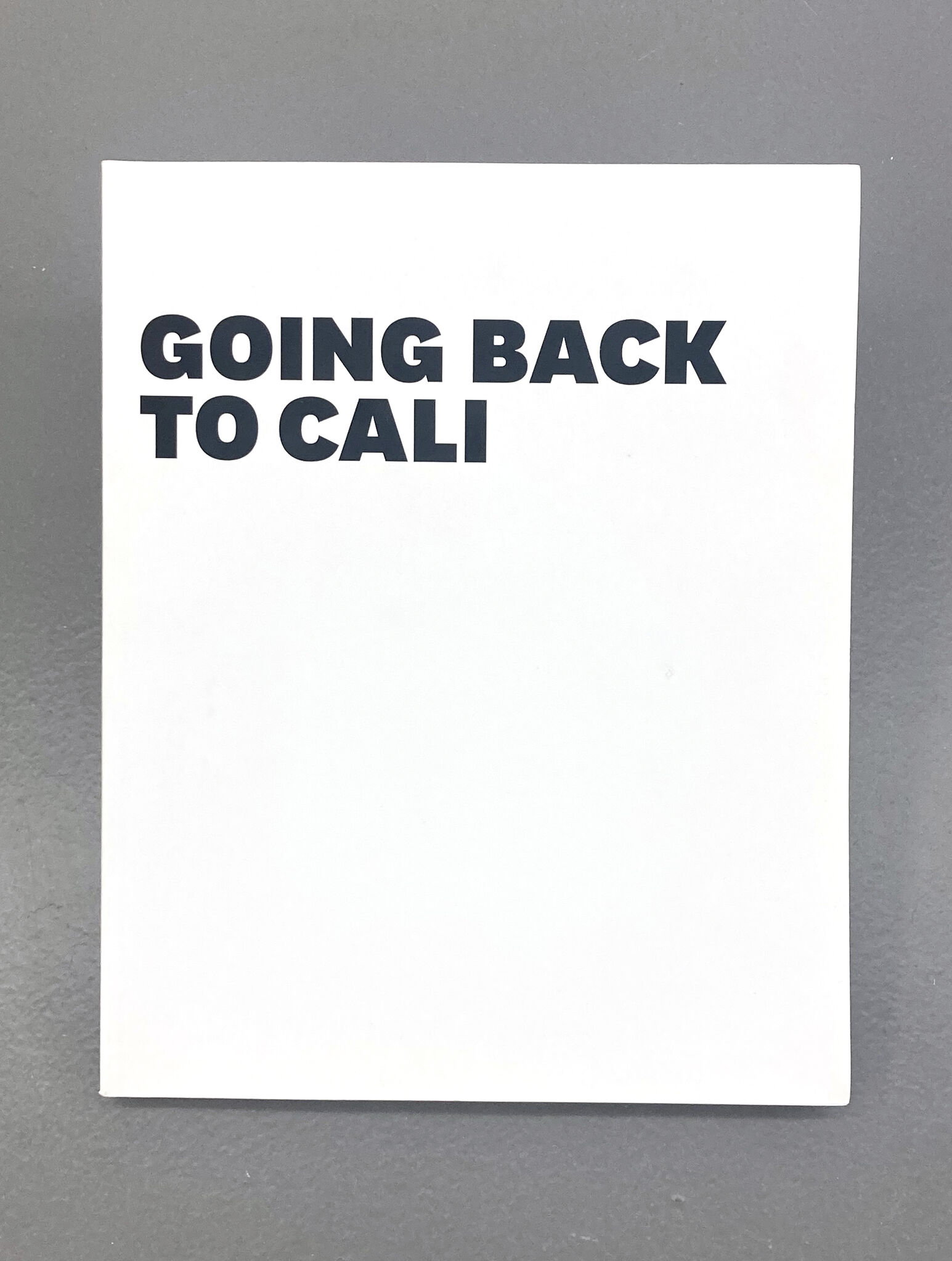

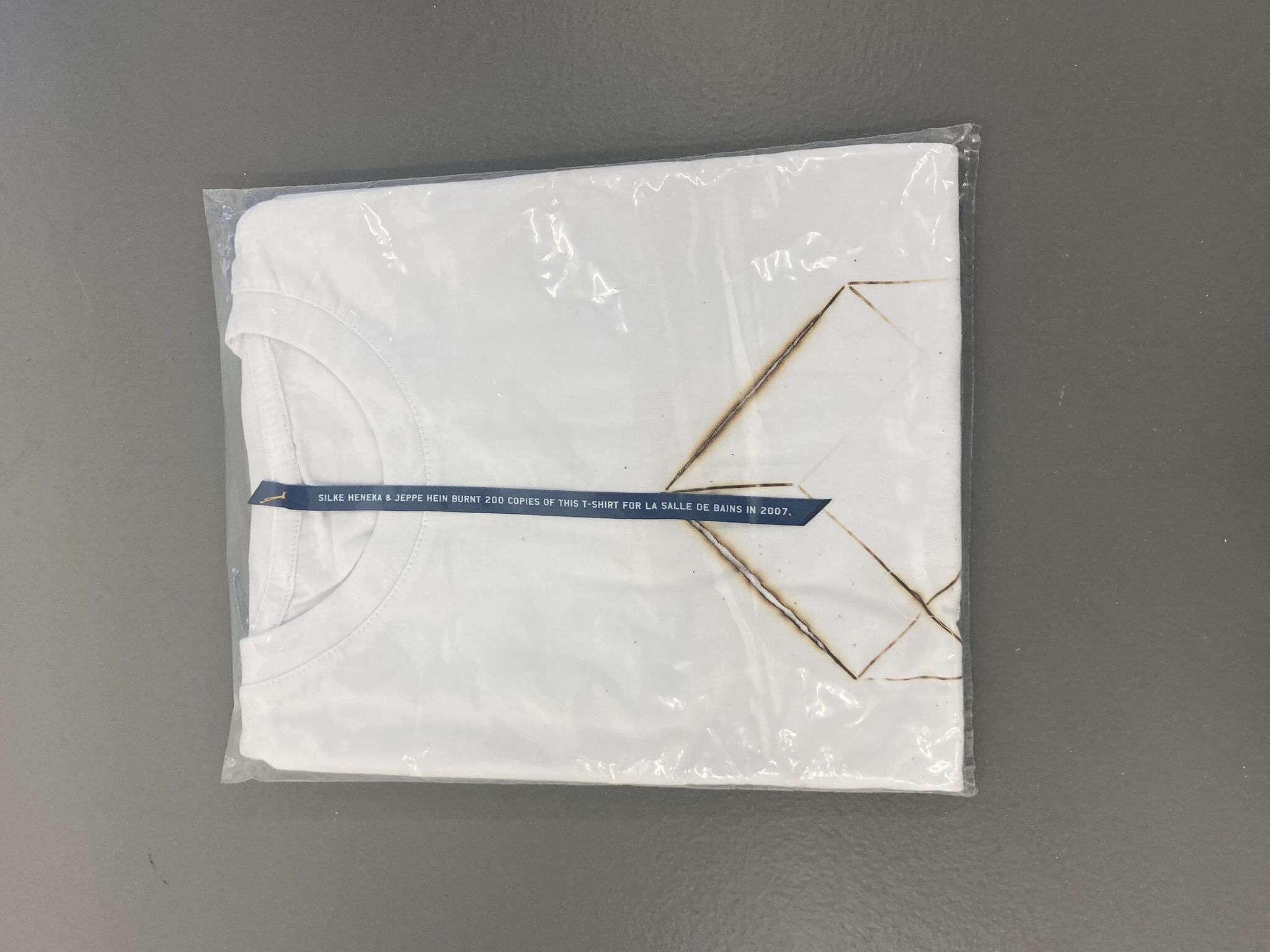

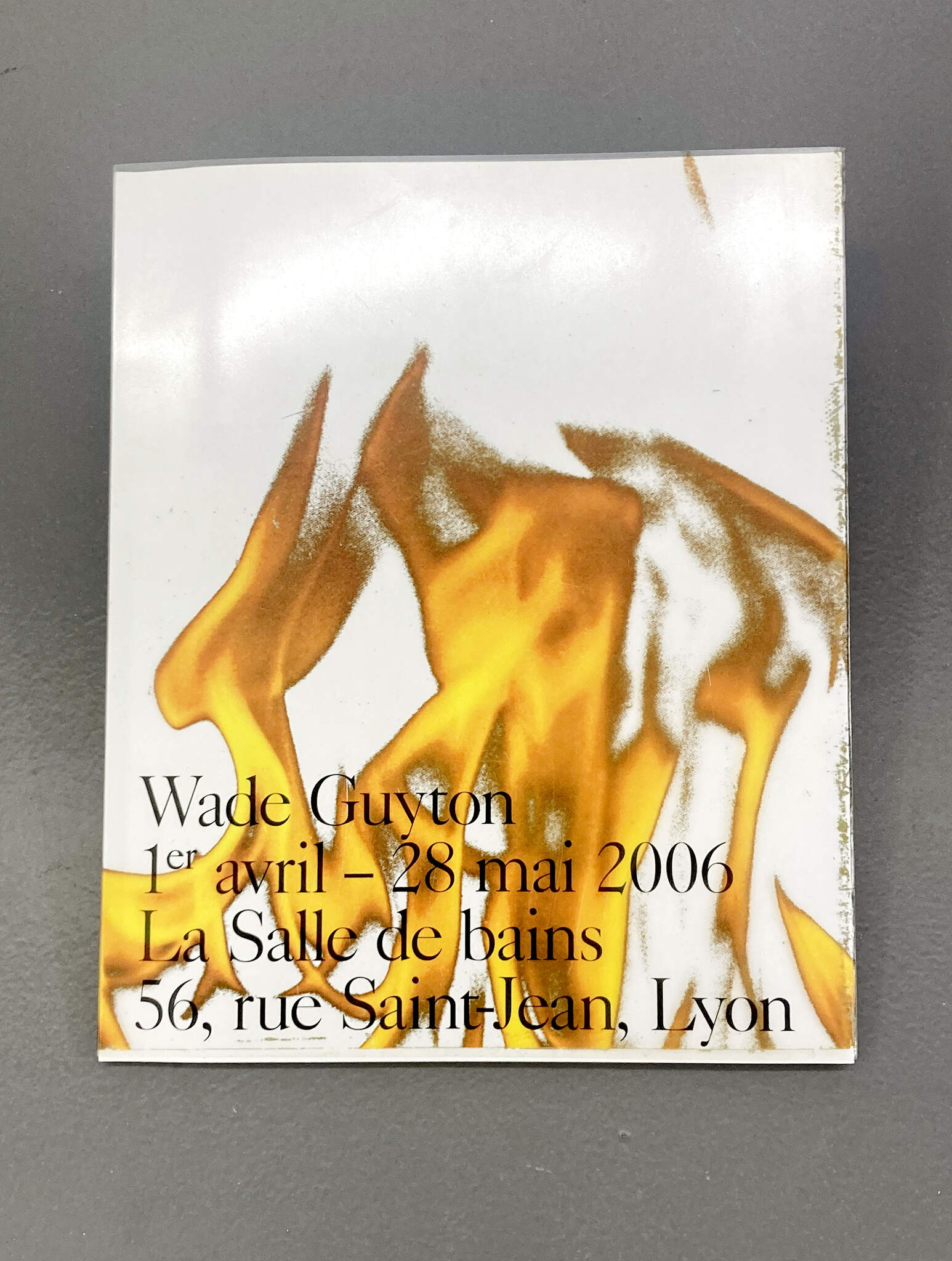

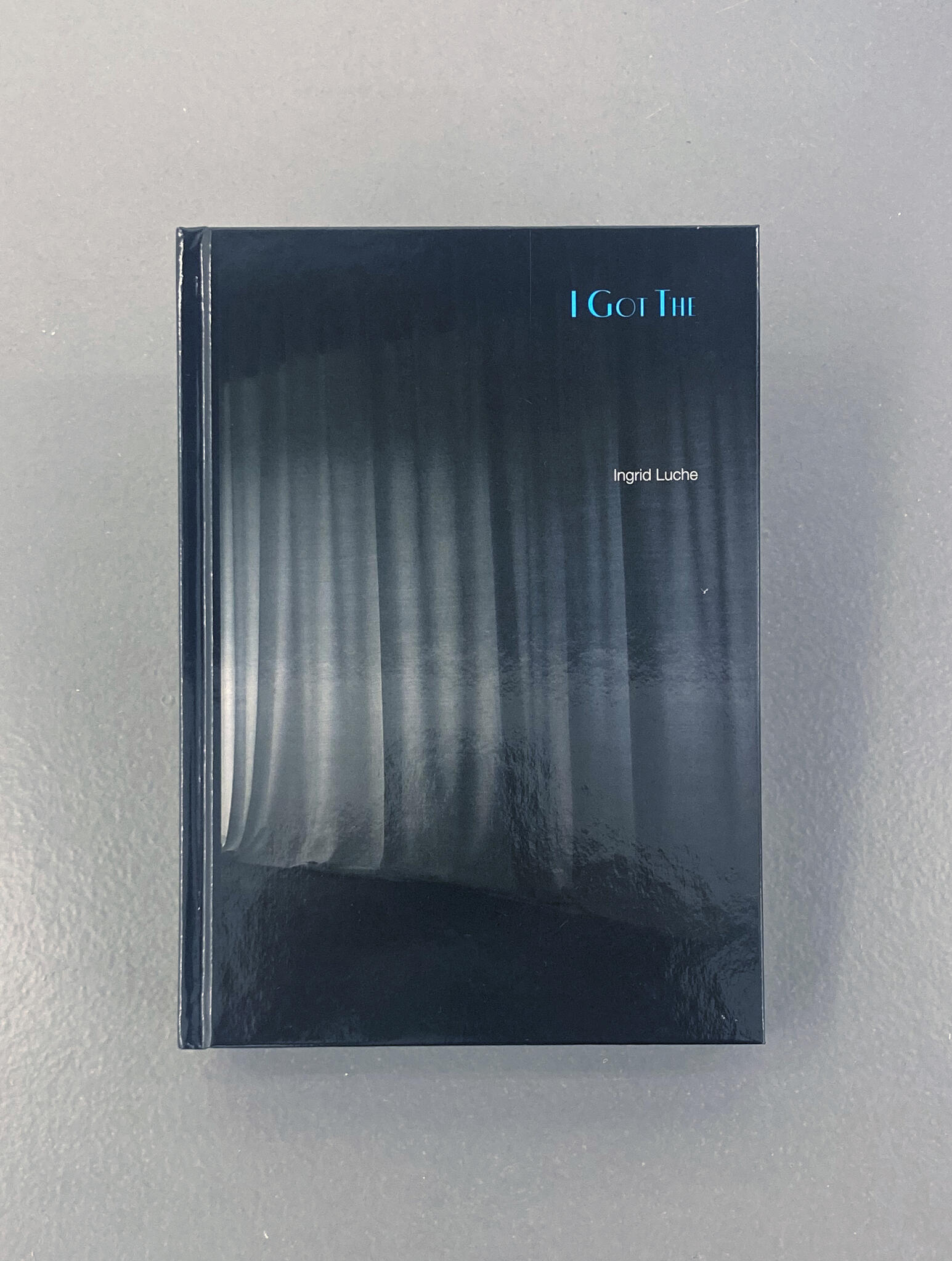

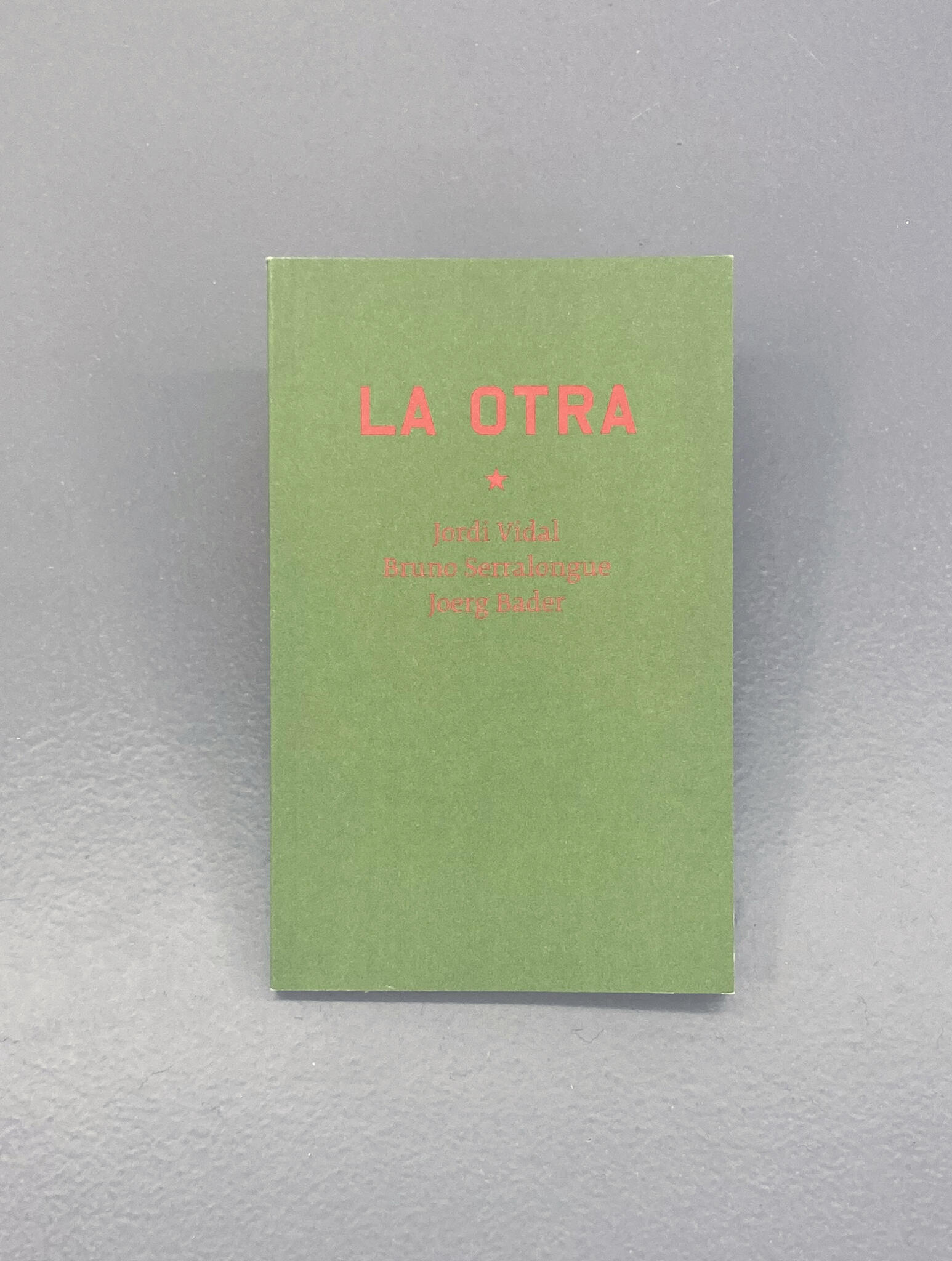

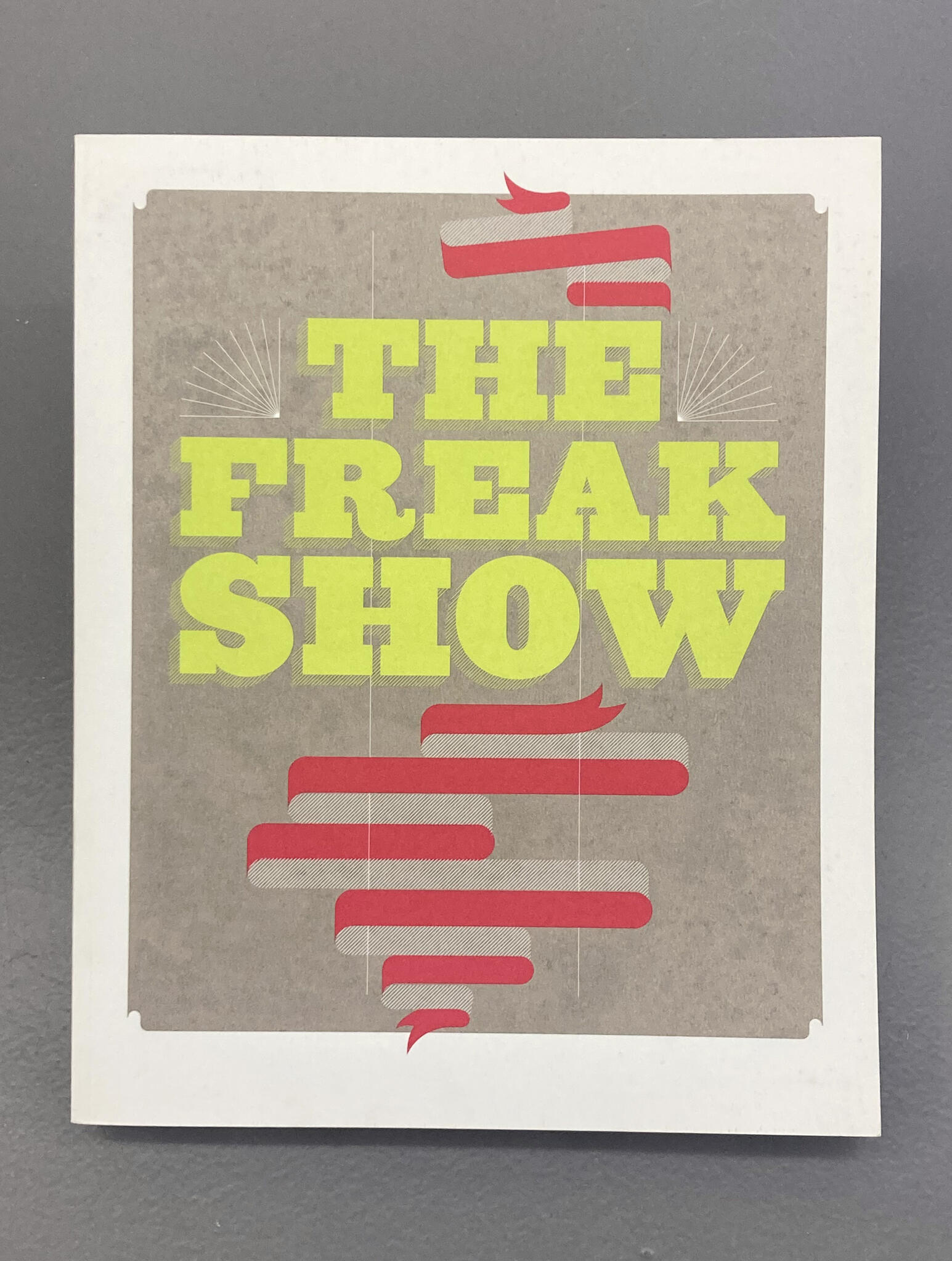

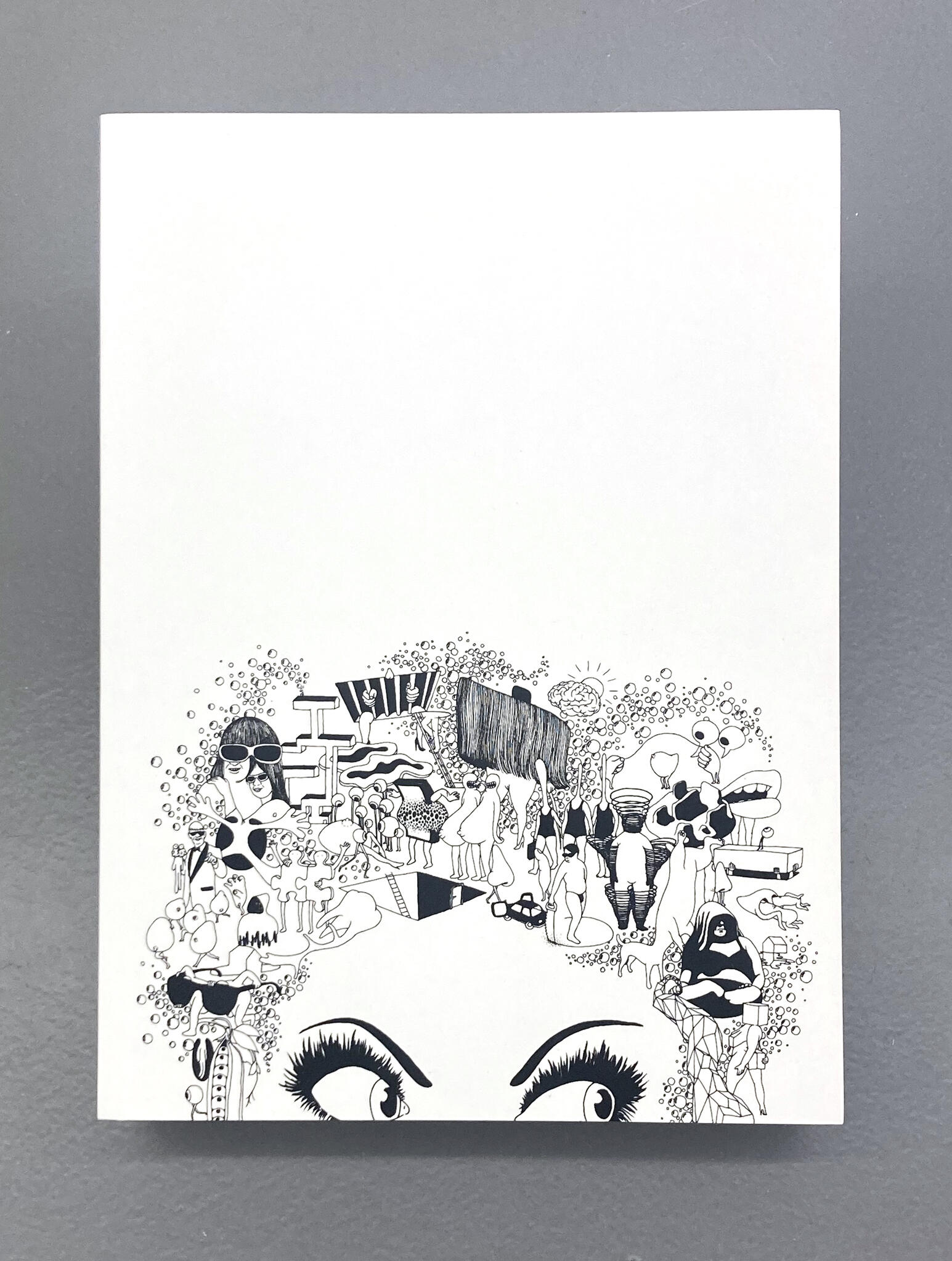

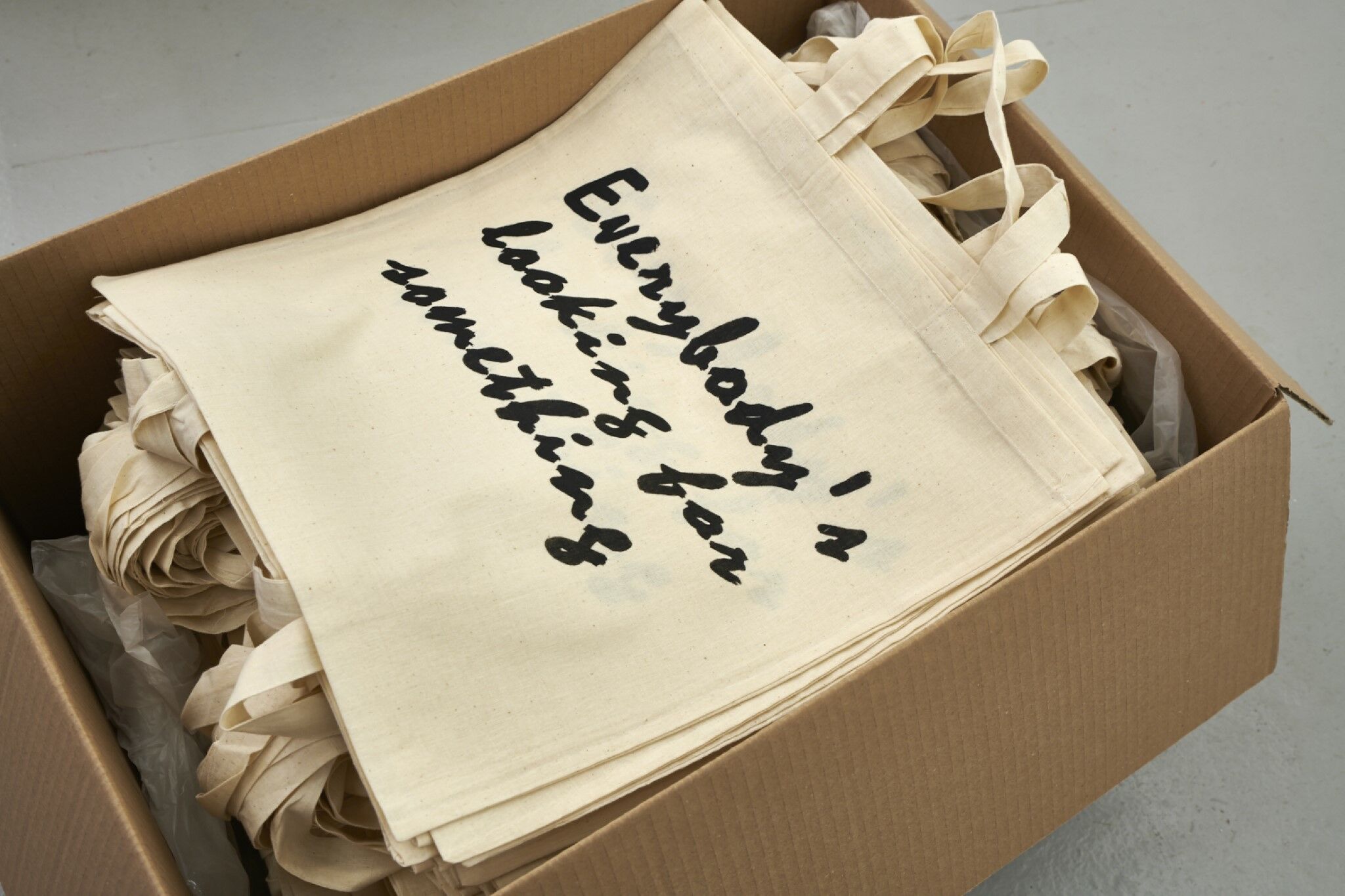

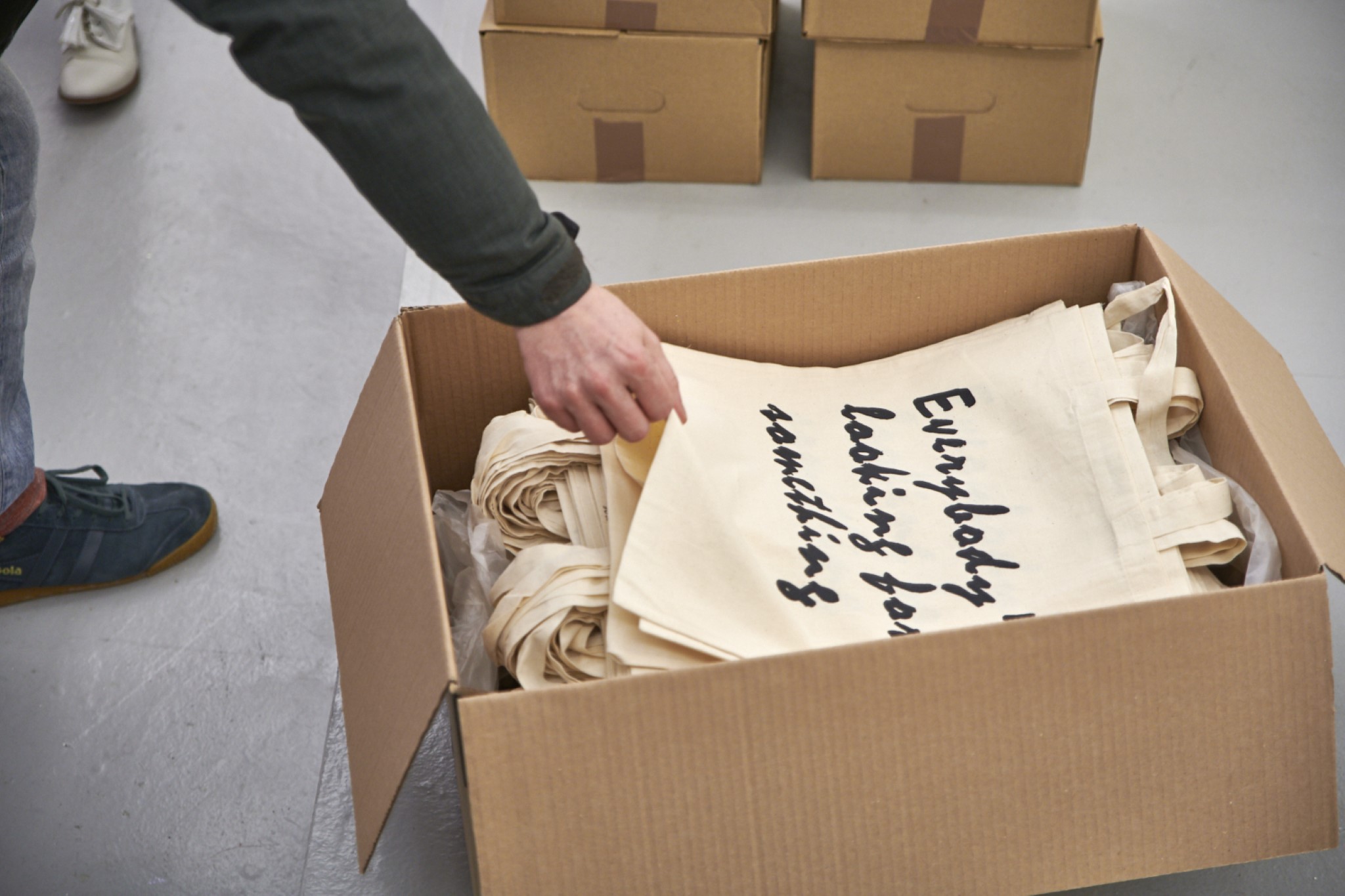

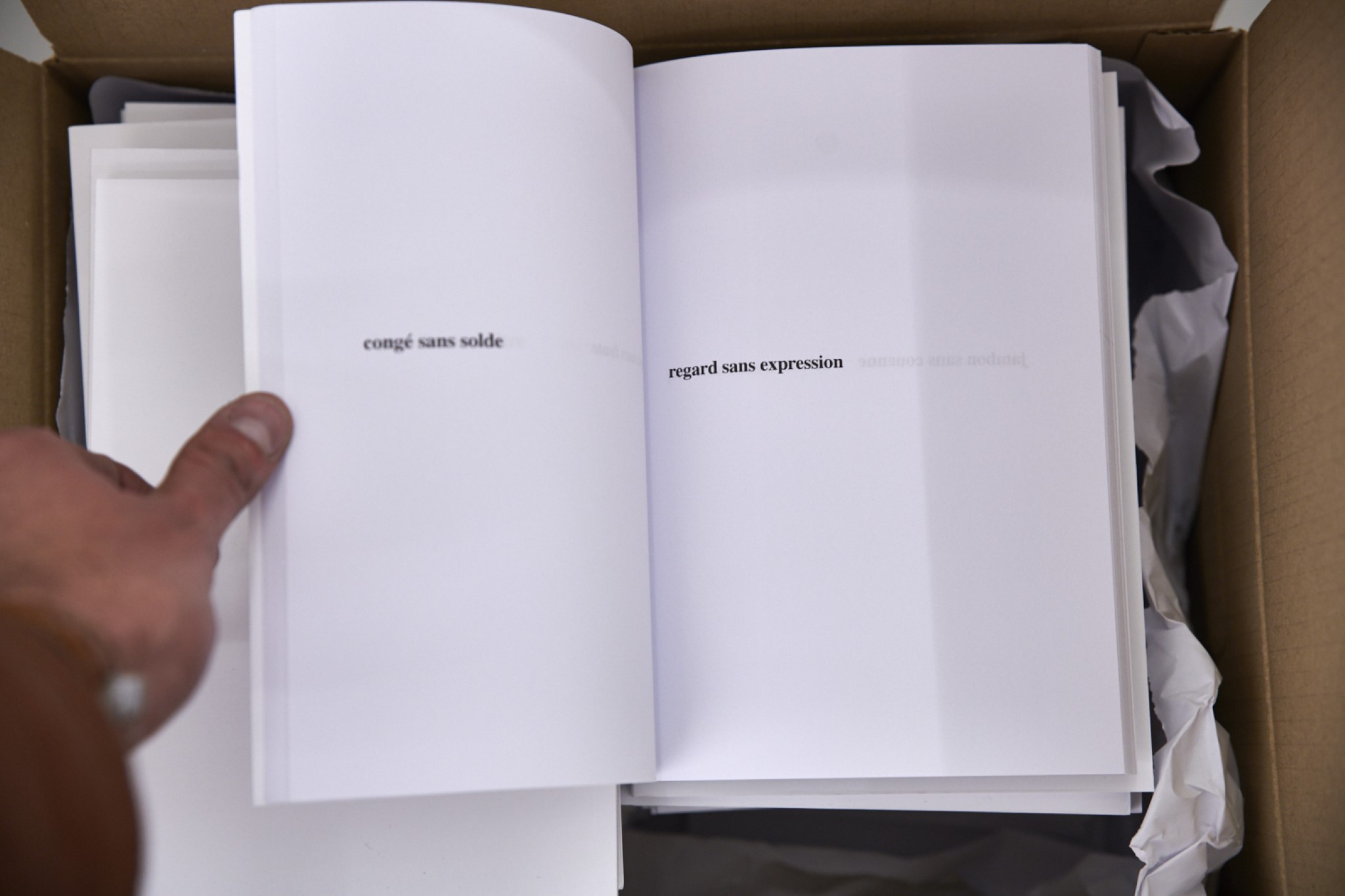

Dans la salle 2 de l’exposition Everybody’s Looking For Something, les peintures se sont retirées – elles reviendront en nombre dans la salle 3 – tandis qu’aux questions esthétiques posées plus haut se présente un cas concret sur le mode du déstockage. Si les regardeurs ne savent pas exactement ce qu’ils viennent chercher, au moins pourront-ils repartir avec un sac ou un livre, ou les deux, voire même glisser l’un dans l’autre ce qui relèverait du bon sens. De plus, ce geste mimétique accentuerait le dérèglement du système d’échange qui a lieu dans tout dispositif de don ou de mise à disposition gratuite d’une édition d’artiste dans un espace d’exposition. D’abord, ne nous méprenons pas sur le statut du sac sérigraphié où l’on retrouve le titre de l’exposition. Contrairement aux apparences, il ne s’agit pas d’un produit dérivé, mais, selon un principe de migration des signes et des motifs d’un registre à l’autre, de l’art au design ou au marketing et inversement – l’histoire de l’art moderne s’est faite ainsi – il envisage le devenir peinture de la formule générique (ou du refrain). D’ailleurs, qui nous dit que le titre est venu avant l’édition et que l’édition ne vient pas après l’idée d’une peinture dans l’espace public, par exemple ? Le titre fait ici l’objet d’une peinture inédite, qui n’existe pour l’instant que sous une forme éditée ; quant au livre, il voit ici le premier lancement de sa réédition. Comme souvent, la diffusion de l’édition va procéder à la disparition de celle-ci, et si l’on tient aux métonymies, à la disparition du titre. Il convient alors de considérer le livre, qui n’est pas un livre sans titre, mais dont le titre est bien Sans-Titre, ce qui a pour vertu d’introduire les qualités poétiques de ces syntagmes privatifs (« vivre sans complexe », « maïs sans OGM »), mélioratifs à quelques exceptions près (« chambre sans fenêtre », « soutien-gorge sans armature »), trouvés dans la forêt de signes que compose la vie quotidienne. C’est précisément la destination de la peinture-titre colportée discrètement par le tote bag, sa raison d’être étant d’être vu. Ainsi l’épaule du regardeur à la recherche de quelque chose, comme tout le monde, sera-t-elle, le temps d’une course, le lieu de l’exposition.

Il était plus périlleux d’établir un rapport avec le refrain des Eurythmics ou même la musique new wave, à moins de pousser l’analyse de cette couleur étrange choisie pour y accrocher les tableaux : un mauve iridescent aux connotations confuses (electro-pop tirant sur le glam-rock, punk-gothique, pouvant évoquer la décoration d’un bar à chicha ou d’un « point soleil »). Elle avait pour effet de tester la manière dont la peinture résiste, avec peu de moyens, aux sollicitations du mur et aux imprévus. Le texte qui accompagnait la salle 1 en proposait une interprétation littérale, ce qui n’écarte jamais définitivement les affres de l’équivocité qu’escortent souvent les tourments de la tautologie : la formule générique, prise au pied de la lettre et dans les circonstances présentes, exposait l’exposition elle-même à la question de ce que viennent y chercher les visiteurs, supposant que l’œil, devant la peinture, est un organe insatiable et que son avidité diffère sans cesse le moment de se demander ce qu’on attend (encore) de l’art.

Dans la salle 2 de l’exposition Everybody’s Looking For Something, les peintures se sont retirées – elles reviendront en nombre dans la salle 3 – tandis qu’aux questions esthétiques posées plus haut se présente un cas concret sur le mode du déstockage. Si les regardeurs ne savent pas exactement ce qu’ils viennent chercher, au moins pourront-ils repartir avec un sac ou un livre, ou les deux, voire même glisser l’un dans l’autre ce qui relèverait du bon sens. De plus, ce geste mimétique accentuerait le dérèglement du système d’échange qui a lieu dans tout dispositif de don ou de mise à disposition gratuite d’une édition d’artiste dans un espace d’exposition. D’abord, ne nous méprenons pas sur le statut du sac sérigraphié où l’on retrouve le titre de l’exposition. Contrairement aux apparences, il ne s’agit pas d’un produit dérivé, mais, selon un principe de migration des signes et des motifs d’un registre à l’autre, de l’art au design ou au marketing et inversement – l’histoire de l’art moderne s’est faite ainsi – il envisage le devenir peinture de la formule générique (ou du refrain). D’ailleurs, qui nous dit que le titre est venu avant l’édition et que l’édition ne vient pas après l’idée d’une peinture dans l’espace public, par exemple ? Le titre fait ici l’objet d’une peinture inédite, qui n’existe pour l’instant que sous une forme éditée ; quant au livre, il voit ici le premier lancement de sa réédition. Comme souvent, la diffusion de l’édition va procéder à la disparition de celle-ci, et si l’on tient aux métonymies, à la disparition du titre. Il convient alors de considérer le livre, qui n’est pas un livre sans titre, mais dont le titre est bien Sans-Titre, ce qui a pour vertu d’introduire les qualités poétiques de ces syntagmes privatifs (« vivre sans complexe », « maïs sans OGM »), mélioratifs à quelques exceptions près (« chambre sans fenêtre », « soutien-gorge sans armature »), trouvés dans la forêt de signes que compose la vie quotidienne. C’est précisément la destination de la peinture-titre colportée discrètement par le tote bag, sa raison d’être étant d’être vu. Ainsi l’épaule du regardeur à la recherche de quelque chose, comme tout le monde, sera-t-elle, le temps d’une course, le lieu de l’exposition.

For the exhibition Everybody’s Looking for Something, the first gallery featured five recent paintings by Camila Oliveira Fairclough. The rigorous layout of the show generated a striking contrast with a certain nonchalance that her paintings inspire at first glance. Hence the choice of motifs that are generic (heart, emoji, numerals) or borrowed from an ordinary visual and linguistic environment, as if in painting there were nothing but valid subjects. As for technique, in certain regards it seems to express in Oliveira Fairclough’s work a carefree attitude that goes so far as to leave the pencil lines of the drawing visible, as if complete and incomplete were equivalent. In fact, it springs from the artist’s great mastery of gesture, where all modulations (speed of the brush, quantity of paint) are the result of precise decisions, while spontaneity is always backed up by an analytical approach that is thoroughly grounded in the complete history of modern painting. This poetics of ambivalence was presented then in a display that is both sugary and cool, in which the desire for painting and the stuff of life can reach us through a standardized system (the painting, the exhibition) and even the identification of other systems for producing value and desire (advertising design, poling of client satisfaction). The show’s subtitle then (love, food, money) resonated with the eloquence of paintings like Sunday Brunch or Avec ou sans contact (Contact or Contactless).

It was riskier making a connection with the Eurythmics’ refrain or even New Wave music, that is unless we go more deeply into the analysis of the odd color chosen for the walls behind the hanging paintings, i.e., an iridescent mauve with confusing connotations (electro-pop tending towards glam rock, and gothic punk, possibly suggesting the décor of a hookah bar or a tanning salon). This had the effect of testing how Oliveira Fairclough’s painting, with only a few resources available, worked against both the appeal of the wall and the unexpected. The text provided in Gallery 1 proposed a literal interpretation, which never dismisses once and for all the torture of ambiguity that often goes hand in hand with the torments of tautology. That is, the generic formula, taken literally and in light of the present circumstances, exposed the exhibition itself to the question of what visitors come looking for, supposing that the eye in front of paintings is an insatiable organ and that its voraciousness endlessly puts off the moment of wondering what one (still) expects of art.

In Gallery 2 of Everybody’s Looking for Something, the paintings have been withdrawn – they will be back and in droves for Gallery 3 – while the esthetic questions raised above face a concrete case in terms of destocking, of reducing inventory. If viewers don’t know exactly what they’re looking for, at least they will be able to leave with a bag or a book, or both, or even slip one in the other, which would be simple common sense. Moreover, that mimetic gesture would heighten the disruption of the exchange system that occurs in any arrangement for giving away or placing at the public’s disposal free of charge an artist’s edition in an exhibition space. First, let’s be clear about the status of the silk-screened bag, where the exhibition title can be found. Appearances to the contrary, this is not a by-product. Rather, following a principle of the shift of signs and motifs from one register to another, from art to design or marketing and vice versa – the history of modern art took shape in this way – the tote bag with its title envisions the future of painting from the generic formula (or refrain). Furthermore, who says that the title came before the edition and that the edition doesn’t come after the idea of a painting in a public space, for instance? The title here is the subject of a new painting, which only exists as a published form for now; as for the book, it witnesses here the initial launch of its reedition. As is often the case, the distribution of the edition will effect its disappearance and, if we care for metonymies, the disappearance of the title. We must then consider the book, which is not an untitled book (un livre sans titre) but rather one whose title is indeed Sans Titre, or Untitled, which offers the advantage of introducing the poetic qualities of those privative and ameliorative phrases (“live without fear,” “GM-free corn”), though with a few exceptions (“room without view,” “bra without underwiring”), which are found in the forest of signs making up daily life. That is precisely the destination of the painting-title discreetly being hawked by the tote bag, whose raison d’être is indeed to be seen. Thus, the shoulders of viewers looking for something, just like everybody is, will constitute the exhibition venue, if only the time it takes to do some shopping.

translation: John O'Toole

It was riskier making a connection with the Eurythmics’ refrain or even New Wave music, that is unless we go more deeply into the analysis of the odd color chosen for the walls behind the hanging paintings, i.e., an iridescent mauve with confusing connotations (electro-pop tending towards glam rock, and gothic punk, possibly suggesting the décor of a hookah bar or a tanning salon). This had the effect of testing how Oliveira Fairclough’s painting, with only a few resources available, worked against both the appeal of the wall and the unexpected. The text provided in Gallery 1 proposed a literal interpretation, which never dismisses once and for all the torture of ambiguity that often goes hand in hand with the torments of tautology. That is, the generic formula, taken literally and in light of the present circumstances, exposed the exhibition itself to the question of what visitors come looking for, supposing that the eye in front of paintings is an insatiable organ and that its voraciousness endlessly puts off the moment of wondering what one (still) expects of art.

In Gallery 2 of Everybody’s Looking for Something, the paintings have been withdrawn – they will be back and in droves for Gallery 3 – while the esthetic questions raised above face a concrete case in terms of destocking, of reducing inventory. If viewers don’t know exactly what they’re looking for, at least they will be able to leave with a bag or a book, or both, or even slip one in the other, which would be simple common sense. Moreover, that mimetic gesture would heighten the disruption of the exchange system that occurs in any arrangement for giving away or placing at the public’s disposal free of charge an artist’s edition in an exhibition space. First, let’s be clear about the status of the silk-screened bag, where the exhibition title can be found. Appearances to the contrary, this is not a by-product. Rather, following a principle of the shift of signs and motifs from one register to another, from art to design or marketing and vice versa – the history of modern art took shape in this way – the tote bag with its title envisions the future of painting from the generic formula (or refrain). Furthermore, who says that the title came before the edition and that the edition doesn’t come after the idea of a painting in a public space, for instance? The title here is the subject of a new painting, which only exists as a published form for now; as for the book, it witnesses here the initial launch of its reedition. As is often the case, the distribution of the edition will effect its disappearance and, if we care for metonymies, the disappearance of the title. We must then consider the book, which is not an untitled book (un livre sans titre) but rather one whose title is indeed Sans Titre, or Untitled, which offers the advantage of introducing the poetic qualities of those privative and ameliorative phrases (“live without fear,” “GM-free corn”), though with a few exceptions (“room without view,” “bra without underwiring”), which are found in the forest of signs making up daily life. That is precisely the destination of the painting-title discreetly being hawked by the tote bag, whose raison d’être is indeed to be seen. Thus, the shoulders of viewers looking for something, just like everybody is, will constitute the exhibition venue, if only the time it takes to do some shopping.

translation: John O'Toole

Liste des œuvres :

List of works :

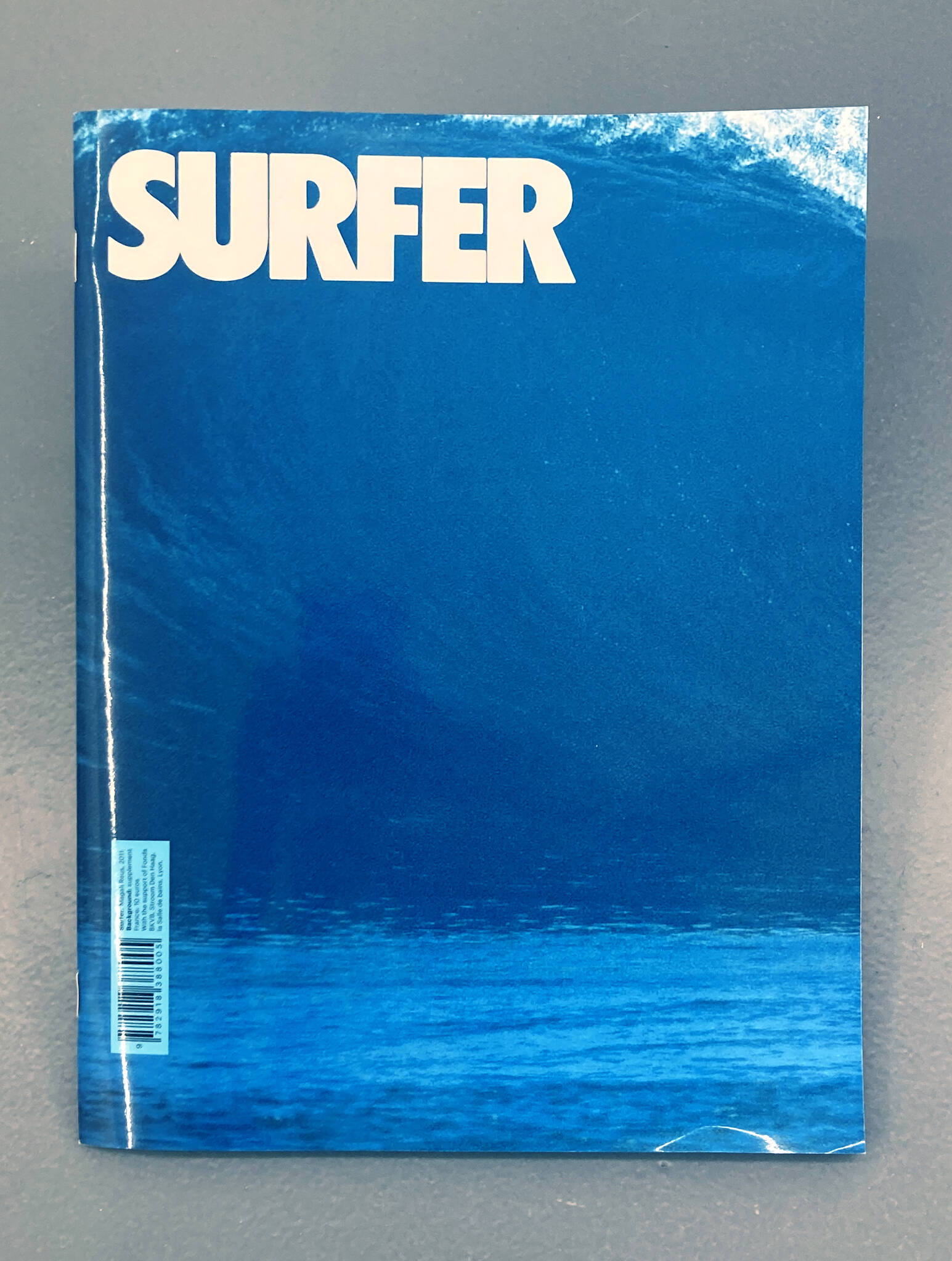

Everybody’s Looking For Something, 2019

sérigraphie sur sac en toile

réalisation Atelier Arcay

édition la Salle de bains

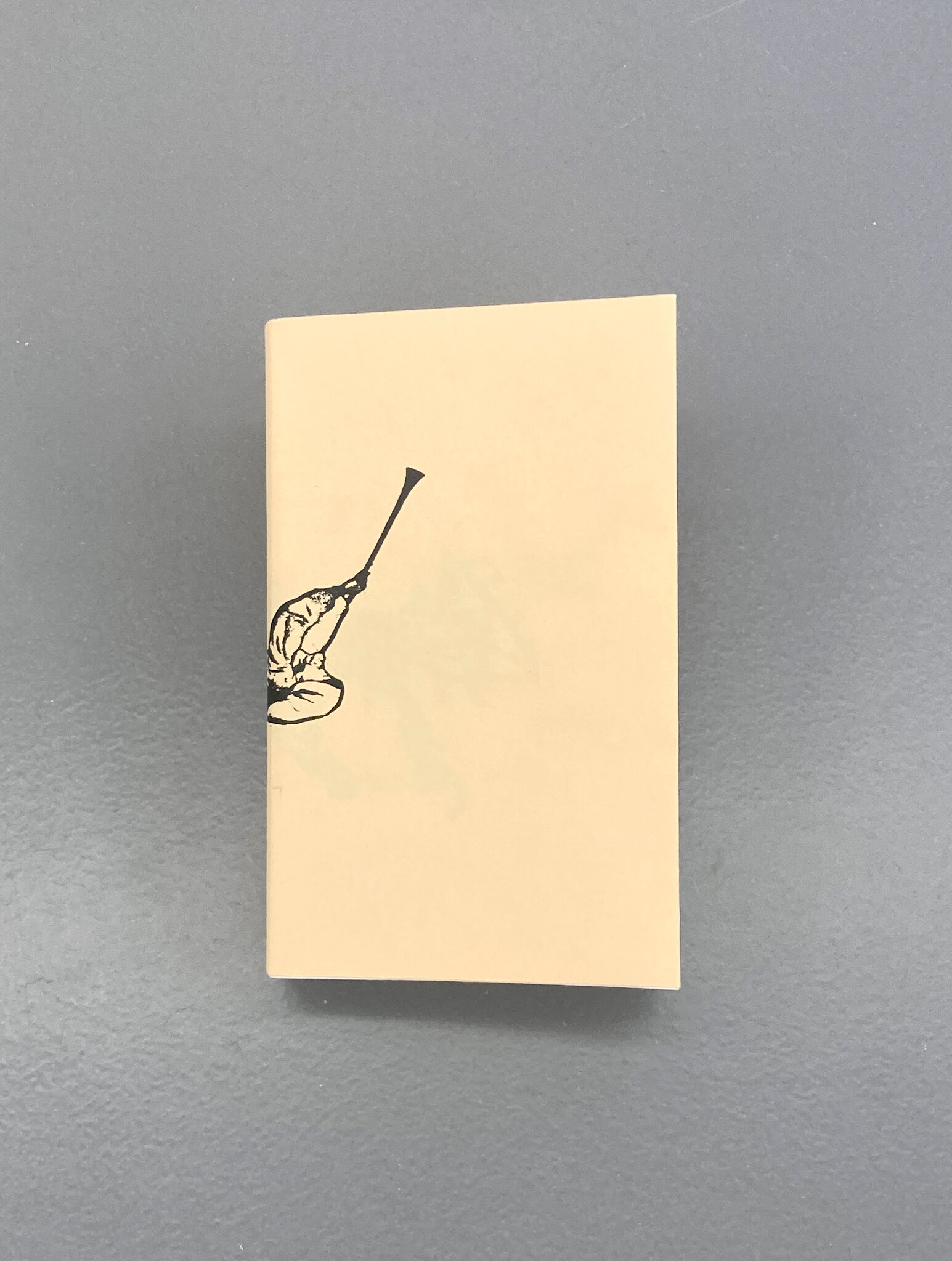

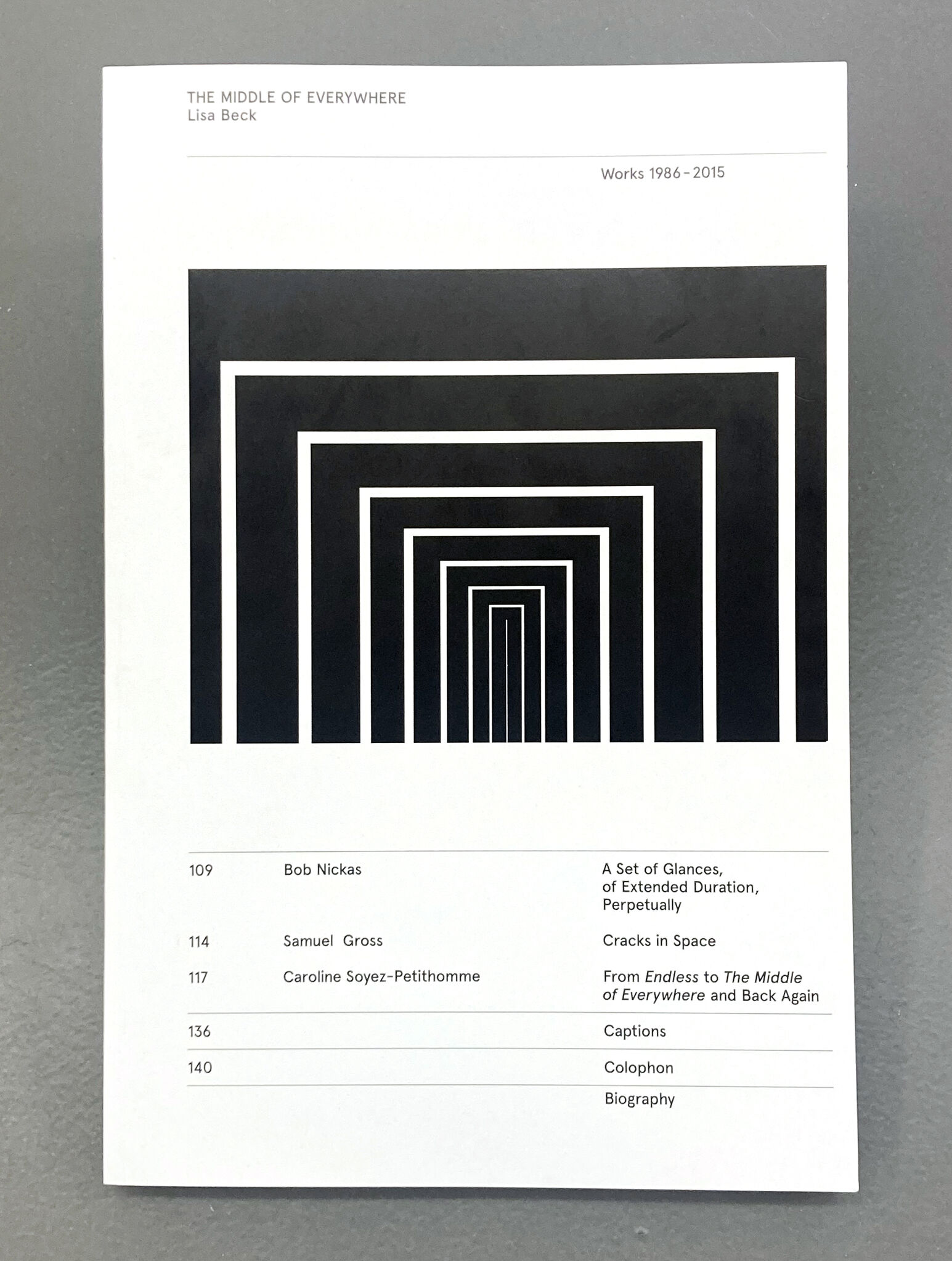

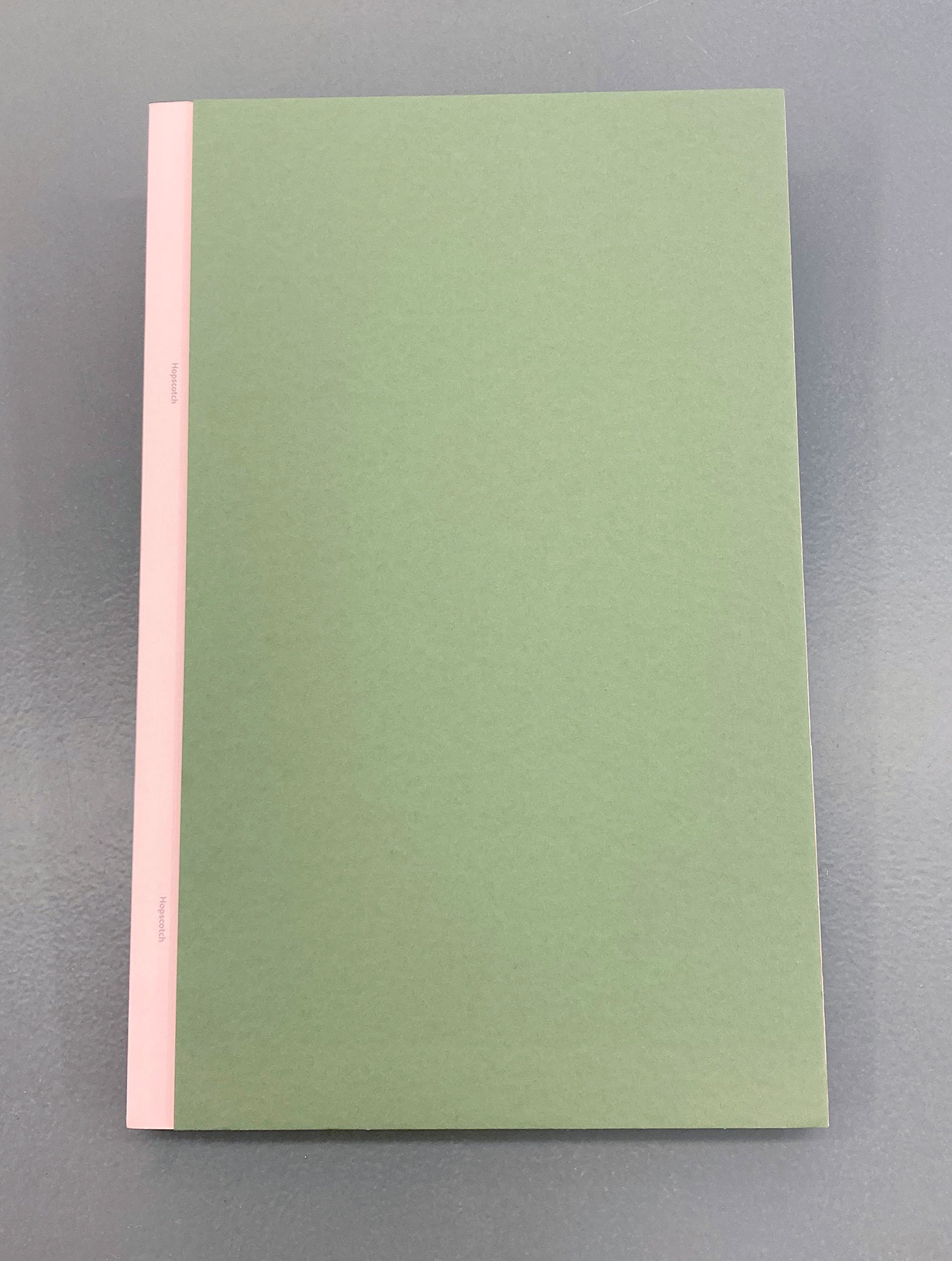

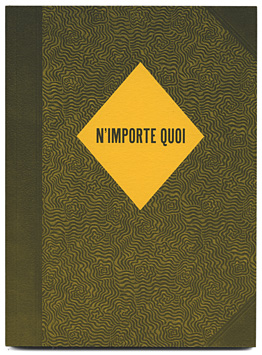

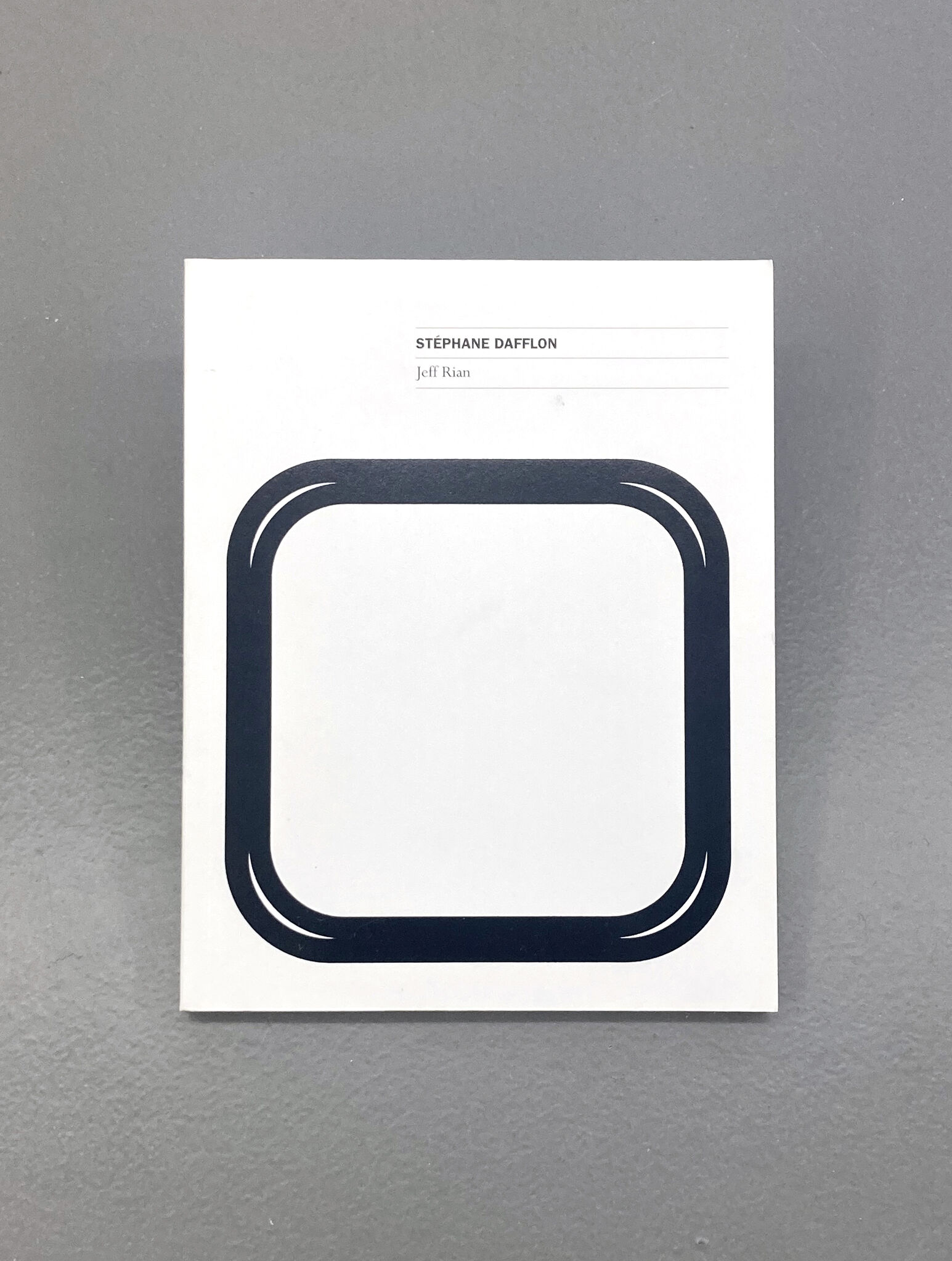

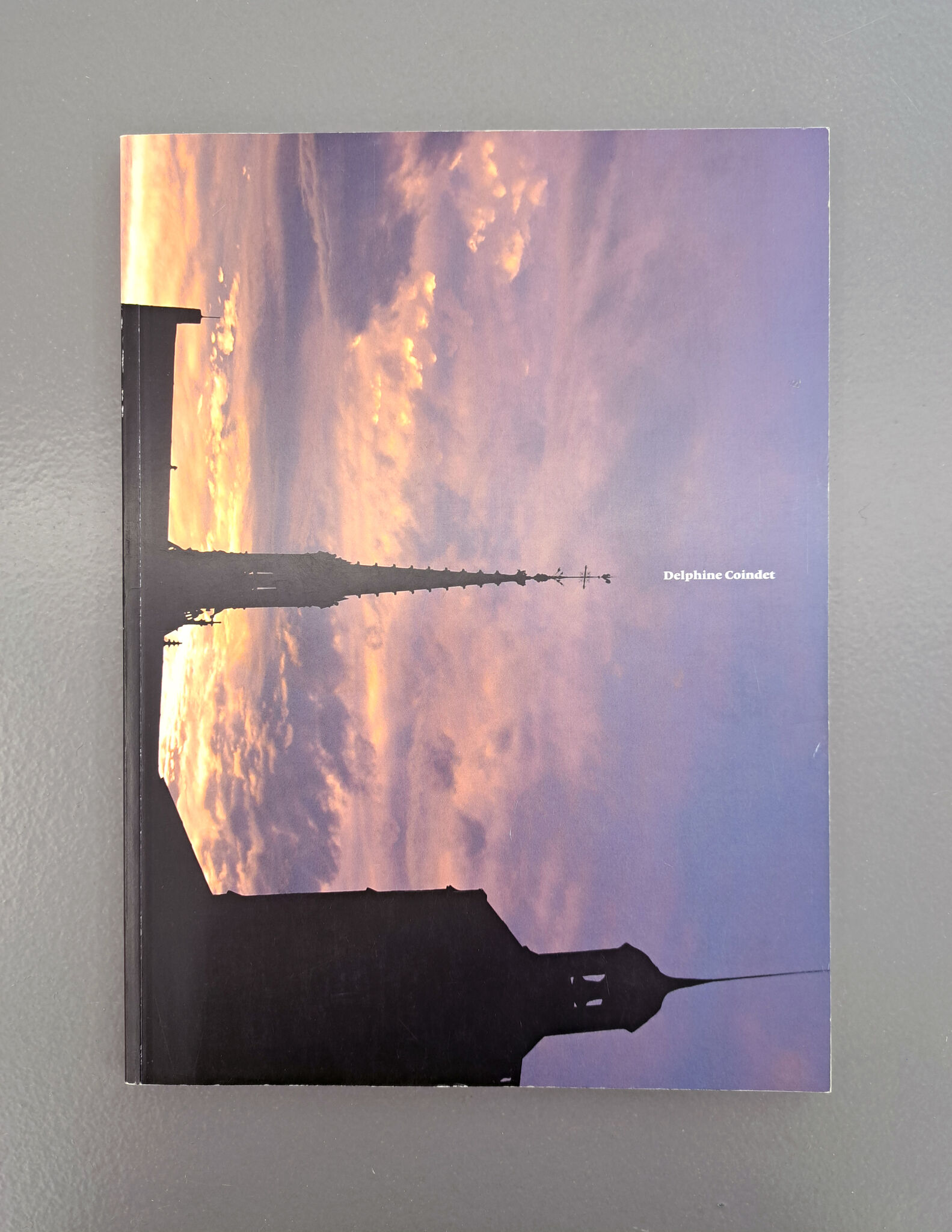

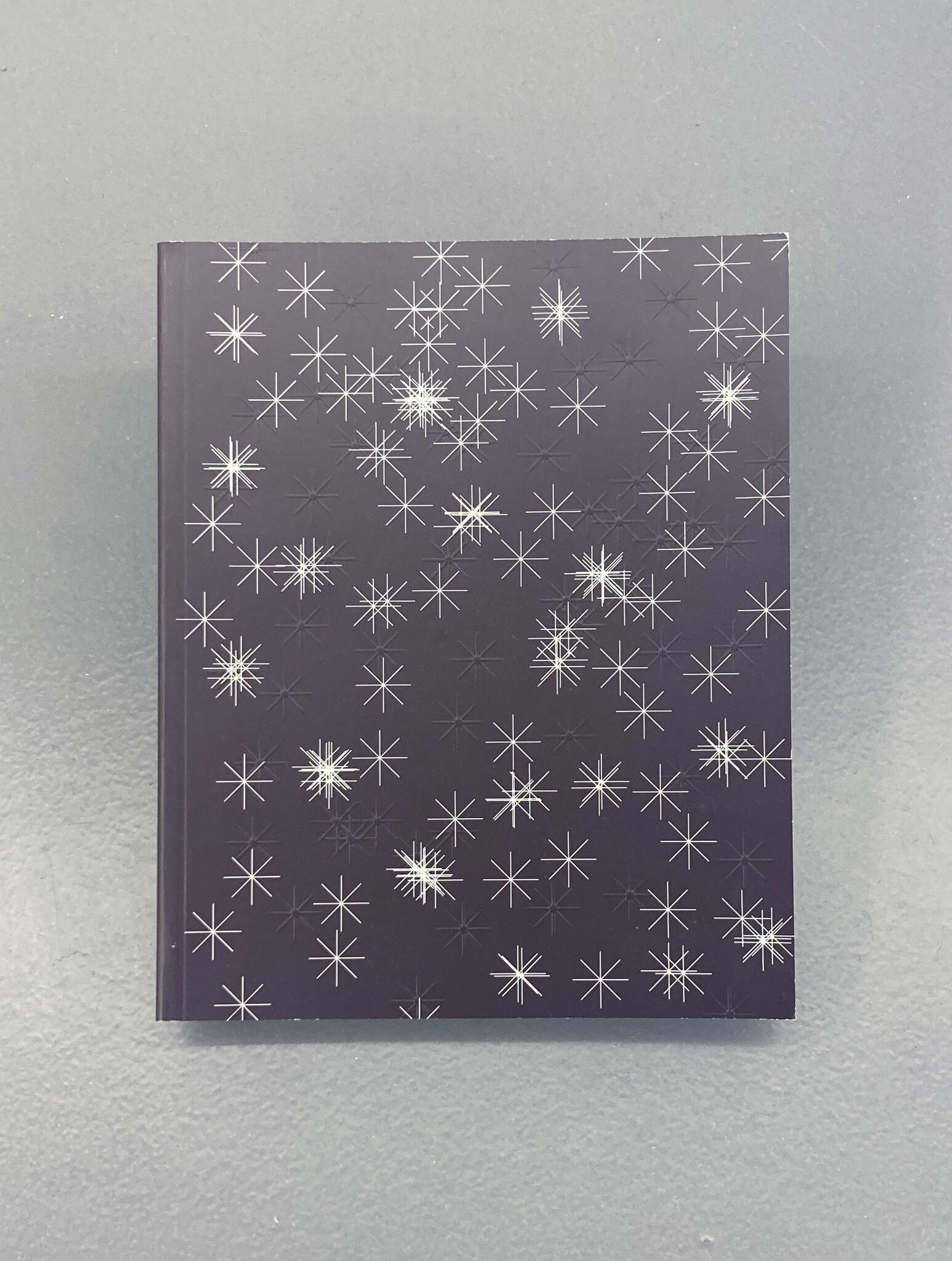

Sans Titre, 2019

livre d'artiste, 112 pages

édition la Salle de bains

sérigraphie sur sac en toile

réalisation Atelier Arcay

édition la Salle de bains

Sans Titre, 2019

livre d'artiste, 112 pages

édition la Salle de bains

Everybody’s Looking for Something, 2019

silk-screen on cloth bag

produced by Atelier Arcay

edition la Salle de bains

Sans-Titre, 2019

artist book, 112 pages

edition la Salle de bains

silk-screen on cloth bag

produced by Atelier Arcay

edition la Salle de bains

Sans-Titre, 2019

artist book, 112 pages

edition la Salle de bains

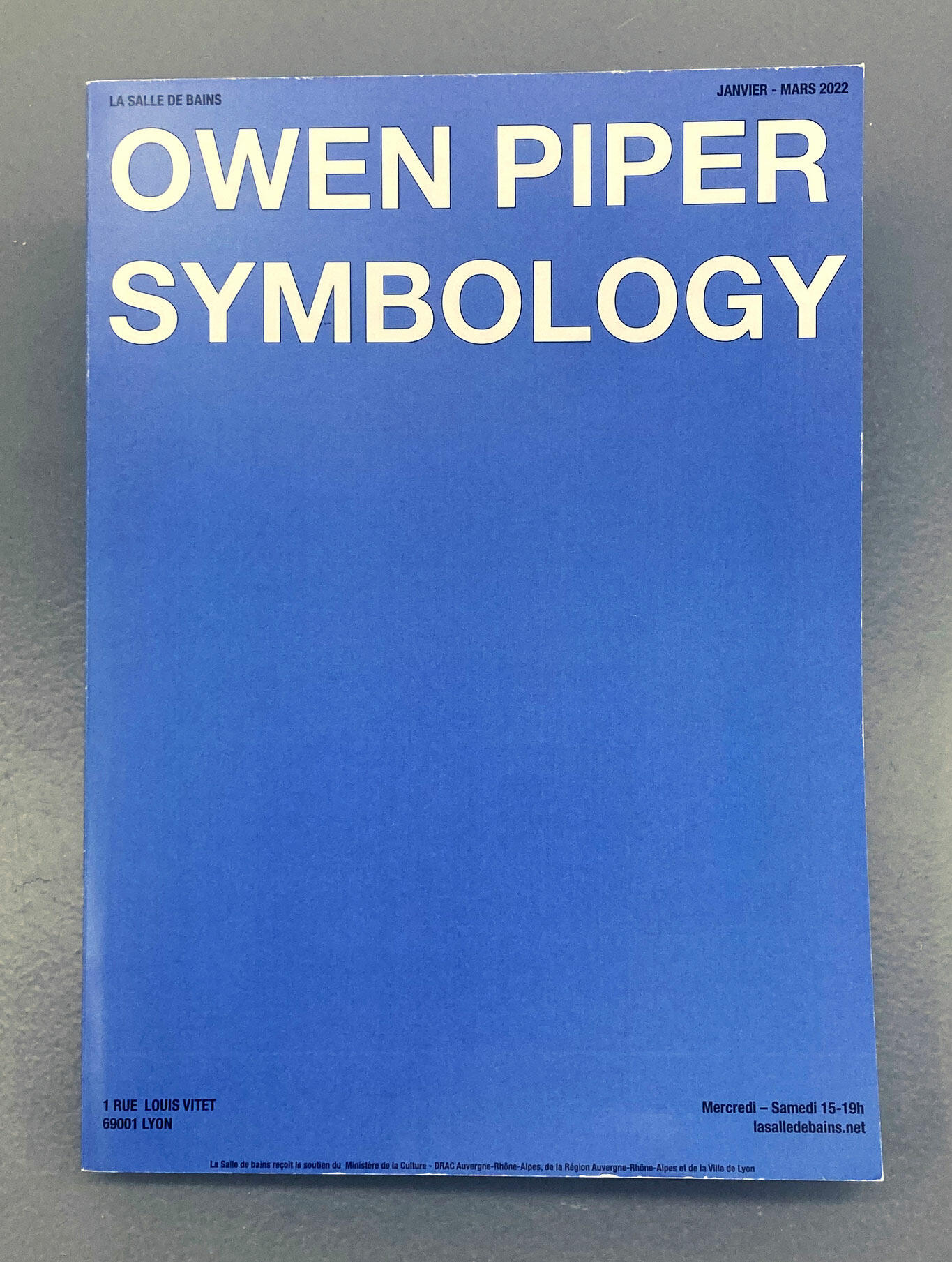

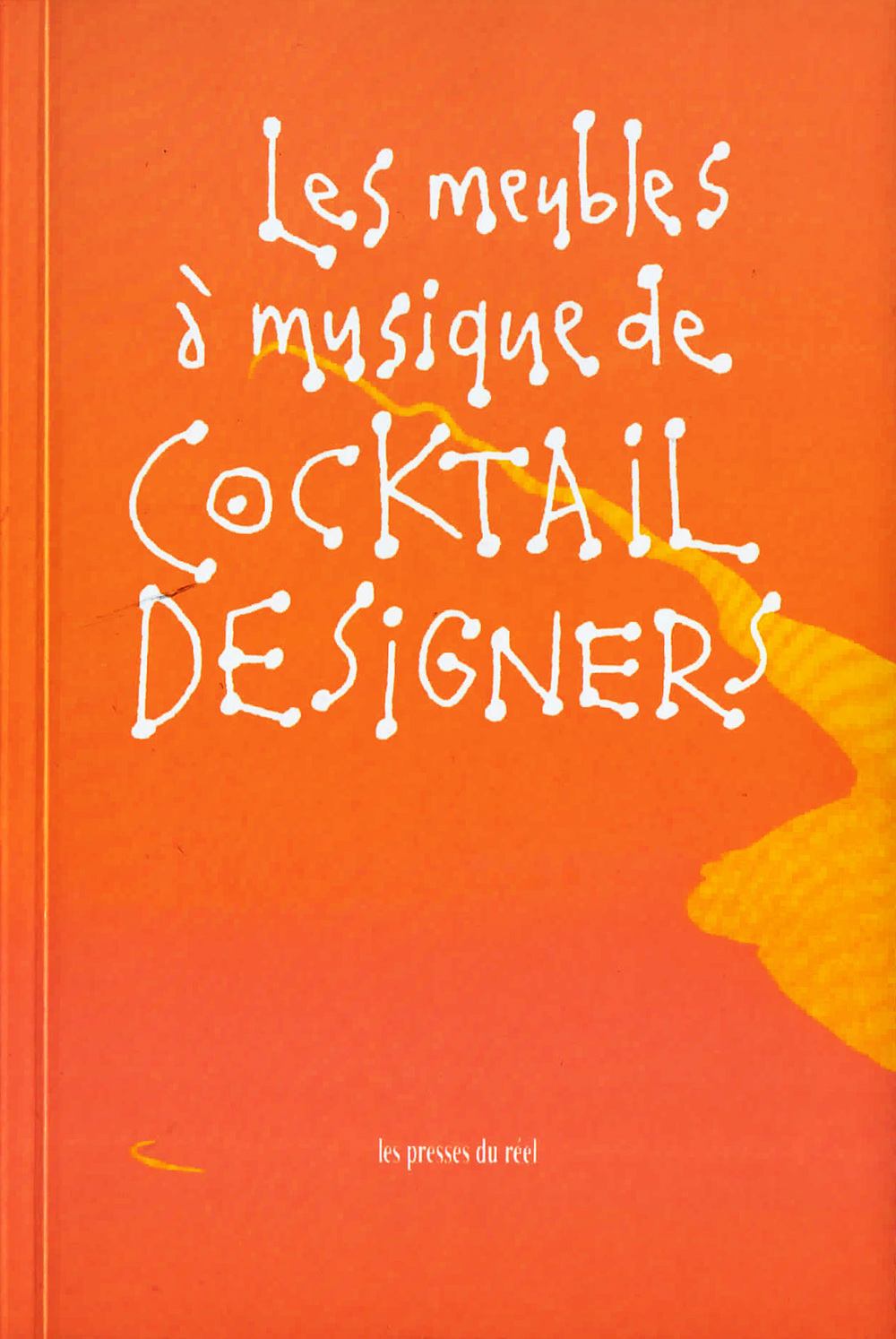

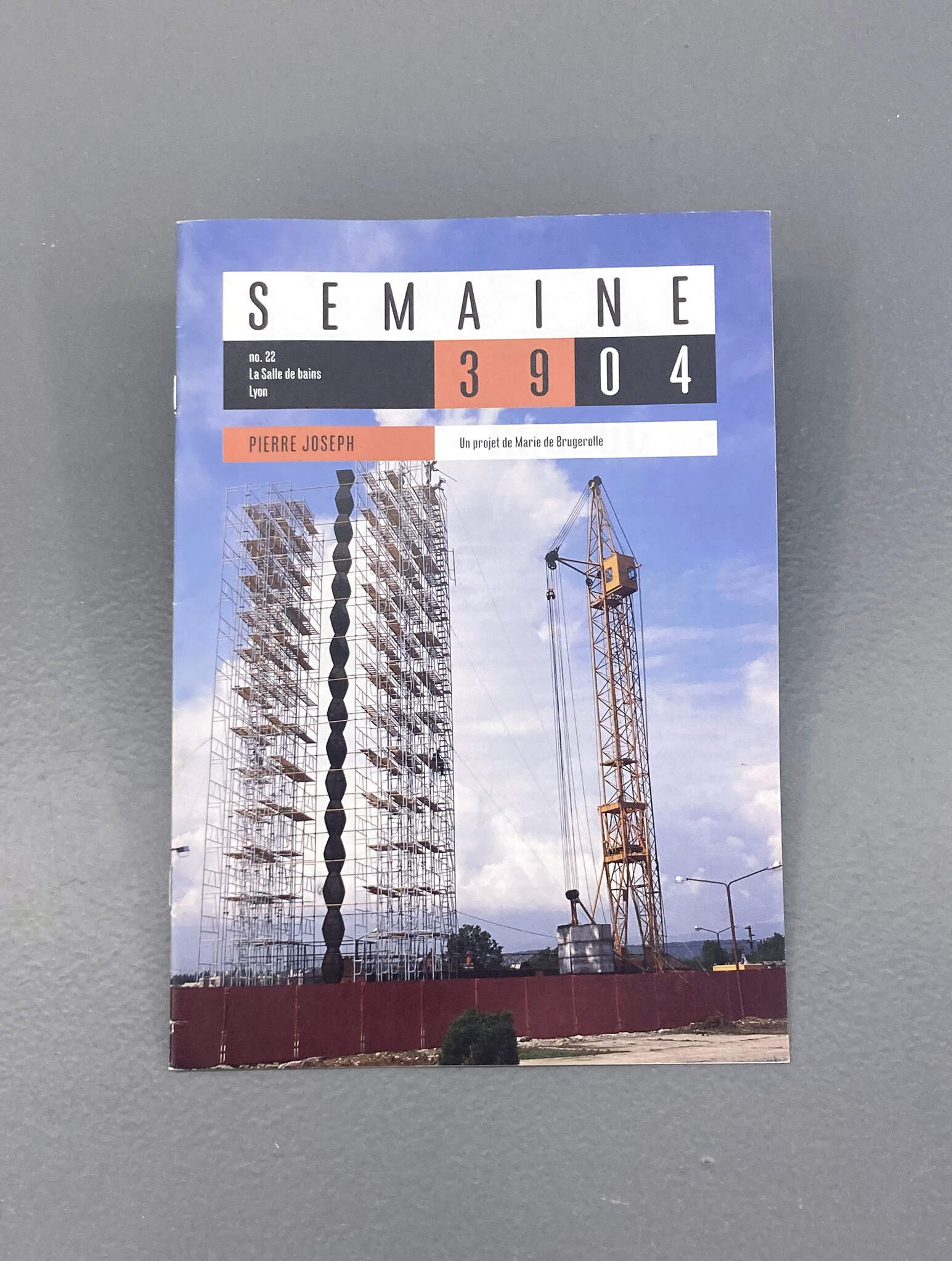

Everybody's looking for something - salle 2, 2019

Affiche - Graphisme : Intercouleur

Camila Oliveira Fairclough est née en 1979 à Rio de Janeiro, Brésil. Elle vit et travaille à Paris. Son travail est représenté par la Galerie Luis Adelantado (Valencia) et Joy de Rouvre (Genève). Elle est cette année artiste en résidence dans le cadre du Programme Accélérations/Centre Pompidou.

Expositions (sélection) : Shaka Sign, Galeria Cavalo, Rio de Janeiro (2018) ; Paris Peinture, Le Quadrilatère, Beauvais (2018), La réalité viscérale, Centre d’Art Les Bains Douches, Alençon (2018) ; The Fables of the Fountain, Super Dakota Gallery, Bruxelles (2018) ; Flatland / Abstractions Narratives #2, MUDAM, Luxembourg (2017) ; Time passes through my hands like dry sand, Ellen de Bruijne Projects/Dolores, Amsterdam (2017) ; Peindre, dit-elle, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Dole (2017) ; Un dos one two, Galeria Luis Adelantado, Valencia (2016) ; Jan-Ken-Pon, La vitrine FRAC Ile-de-France, Le Plateau (2016) ; 360°, Galerie Joy de Rouvre, Genève (2016) ; We always turn our backs to the setting sun, Chiso Galerie, Kyoto (2016) ; Café In, MuCEM, Marseille (2016) ; Thirty Shades of White, Galerie Praz-Delavallade, Paris (2016) ; Dust : The plates of the present, The Camera Club, New York (2015) ; N a pris les dés, Galerie Air de Paris (2015) ; Préférer le moderne à l’ancien, Frac Aquitaine, Bordeaux (2014) ; Wild patterns, Galerie van Gelder, Amsterdam (2014) ; Re : publica, Museu da Republica, Rio de Janeiro (2014) ; Il retro del manifesto, Villa Médicis, Rome (2013) ; Armer les toboggans, Le Quartier, Quimper (2012) ; Boosaards, MoinsUn, Paris (2011) ; Chhuttt... Le merveilleux dans l'art contemporain, Crac Alsace, Altkirch (2009).

Expositions (sélection) : Shaka Sign, Galeria Cavalo, Rio de Janeiro (2018) ; Paris Peinture, Le Quadrilatère, Beauvais (2018), La réalité viscérale, Centre d’Art Les Bains Douches, Alençon (2018) ; The Fables of the Fountain, Super Dakota Gallery, Bruxelles (2018) ; Flatland / Abstractions Narratives #2, MUDAM, Luxembourg (2017) ; Time passes through my hands like dry sand, Ellen de Bruijne Projects/Dolores, Amsterdam (2017) ; Peindre, dit-elle, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Dole (2017) ; Un dos one two, Galeria Luis Adelantado, Valencia (2016) ; Jan-Ken-Pon, La vitrine FRAC Ile-de-France, Le Plateau (2016) ; 360°, Galerie Joy de Rouvre, Genève (2016) ; We always turn our backs to the setting sun, Chiso Galerie, Kyoto (2016) ; Café In, MuCEM, Marseille (2016) ; Thirty Shades of White, Galerie Praz-Delavallade, Paris (2016) ; Dust : The plates of the present, The Camera Club, New York (2015) ; N a pris les dés, Galerie Air de Paris (2015) ; Préférer le moderne à l’ancien, Frac Aquitaine, Bordeaux (2014) ; Wild patterns, Galerie van Gelder, Amsterdam (2014) ; Re : publica, Museu da Republica, Rio de Janeiro (2014) ; Il retro del manifesto, Villa Médicis, Rome (2013) ; Armer les toboggans, Le Quartier, Quimper (2012) ; Boosaards, MoinsUn, Paris (2011) ; Chhuttt... Le merveilleux dans l'art contemporain, Crac Alsace, Altkirch (2009).

Camila Oliveira Fairclough was born in 1979 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. She lives and works in Paris. Her work is represented by the Luis Adelantado Gallery (Valencia) and Joy de Rouvre (Geneva). She is this year’s artist-in-residence at the Pompidou’s Programme Accélérations/Centre Pompidou.

Exhibitions (selection): Shaka Sign, Galeria Cavalo, Rio de Janeiro (2018); Paris Peinture, Le Quadrilatère, Beauvais (2018), La réalité viscérale, Centre d’Art Les Bains Douches, Alençon (2018); The Fables of the Fountain, Super Dakota Gallery, Brussels (2018); Flatland / Abstractions Narratives #2, MUDAM, Luxembourg (2017); Time passes through my hands like dry sand, Ellen de Bruijne Projects/Dolores, Amsterdam (2017); Peindre, dit-elle, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Dole (2017); Un dos one two, Galeria Luis Adelantado, Valencia (2016); Jan-Ken-Pon, La vitrine FRAC Ile-de-France, Le Plateau (2016); 360°, Galerie Joy de Rouvre, Geneva (2016); We always turn our backs to the setting sun, Chiso Gallery, Kyoto (2016); Café In, MuCEM, Marseille (2016); Thirty Shades of White, Galerie Praz-Delavallade, Paris (2016); Dust: The plates of the present, The Camera Club, New York (2015); N a pris les dés, Galerie Air de Paris (2015); Préférer le moderne à l’ancien, Frac Aquitaine, Bordeaux (2014); Wild patterns, Galerie van Gelder, Amsterdam (2014); Re: publica, Museu da Republica, Rio de Janeiro (2014); Il retro del manifesto, Villa Medici, Rome (2013); Armer les toboggans, Le Quartier, Quimper (2012); Boosaards, MoinsUn, Paris (2011); Chhuttt… Le merveilleux dans l’art contemporain, Crac Alsace, Altkirch (2009).

Exhibitions (selection): Shaka Sign, Galeria Cavalo, Rio de Janeiro (2018); Paris Peinture, Le Quadrilatère, Beauvais (2018), La réalité viscérale, Centre d’Art Les Bains Douches, Alençon (2018); The Fables of the Fountain, Super Dakota Gallery, Brussels (2018); Flatland / Abstractions Narratives #2, MUDAM, Luxembourg (2017); Time passes through my hands like dry sand, Ellen de Bruijne Projects/Dolores, Amsterdam (2017); Peindre, dit-elle, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Dole (2017); Un dos one two, Galeria Luis Adelantado, Valencia (2016); Jan-Ken-Pon, La vitrine FRAC Ile-de-France, Le Plateau (2016); 360°, Galerie Joy de Rouvre, Geneva (2016); We always turn our backs to the setting sun, Chiso Gallery, Kyoto (2016); Café In, MuCEM, Marseille (2016); Thirty Shades of White, Galerie Praz-Delavallade, Paris (2016); Dust: The plates of the present, The Camera Club, New York (2015); N a pris les dés, Galerie Air de Paris (2015); Préférer le moderne à l’ancien, Frac Aquitaine, Bordeaux (2014); Wild patterns, Galerie van Gelder, Amsterdam (2014); Re: publica, Museu da Republica, Rio de Janeiro (2014); Il retro del manifesto, Villa Medici, Rome (2013); Armer les toboggans, Le Quartier, Quimper (2012); Boosaards, MoinsUn, Paris (2011); Chhuttt… Le merveilleux dans l’art contemporain, Crac Alsace, Altkirch (2009).

La Salle de bains reçoit le soutien du Ministère de la Culture DRAC Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes,

de la Région Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes et de la Ville de Lyon.

de la Région Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes et de la Ville de Lyon.